Recognizing Israel’s claim to its northernmost territory is likely the best way to avoid future conflict—especially if the Syrian Civil War drags on.

The Golan Heights are back in the news, with concerns that a great power deal on Syria’s future might include renewed demands on Israel to return the territory to the embattled regime of Bashar al-Assad. The Israeli cabinet was helicoptered to the mountain ridge on April 17 for a special session, in which Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared that he wished to “to send a clear message [to the world, that] Israel will never come down from the Golan Heights.”

Netanyahu was right to make such a statement. Whatever the political future of Syria, Middle East regional security requires international recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights. Moreover, as the war-weary great powers seek a comprehensive settlement in Syria, they have a unique political and legal opportunity to do so.

With the rise of terrorism and the collapse of much of the Middle East into near-anarchy, the world is entering uncharted waters in which the normal rules of statecraft and international law offer no clear answers. The international community, therefore, has an opportunity to reinforce a troubled international order by recognizing the border between Syria and Israel east of the Golan Heights. It is vital that the international community conclusively end the ambiguity over the Golan’s fate in order to help stabilize the region in the decades ahead.

The Golan Heights is a strategic ridge abutting the Sea of Galilee. Israel captured the territory in the 1967 Six-Day War when it repelled an invasion by the Syrian army. Rejecting Israel’s surprise offer at the war’s end to return the Heights in exchange for peace, Syria launched a failed but bloody bid to recapture the Heights in the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Israel formally annexed the Golan on December 14, 1981. Three days later, the United Nations Security Council unanimously declared the annexation null and void in Resolution 497, demanding that Israel rescind its decision. Responding to Netanyahu, the Security Council confirmed in April that its resolution still stands.

To date, even Israel’s allies remain unconvinced of its claims to the Golan. The day after Netanyahu vowed that the Heights would “forever remain under Israeli sovereignty,” the U.S. and Germany reaffirmed their position that the Golan is not under Israeli sovereignty in the first place. The U.S. State Department confirmed that it expects the fate of the Heights to be determined via negotiations—although by acknowledging that “the current situation in Syria does not allow this,” spokesman John Kirby implicitly legitimized Israel’s continued hold over the territory pending Syria’s reconstitution.

Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu leads a cabinet meeting held in the Golan Heights, April 17, 2016. Photo: by Effi Sharir / Flash90

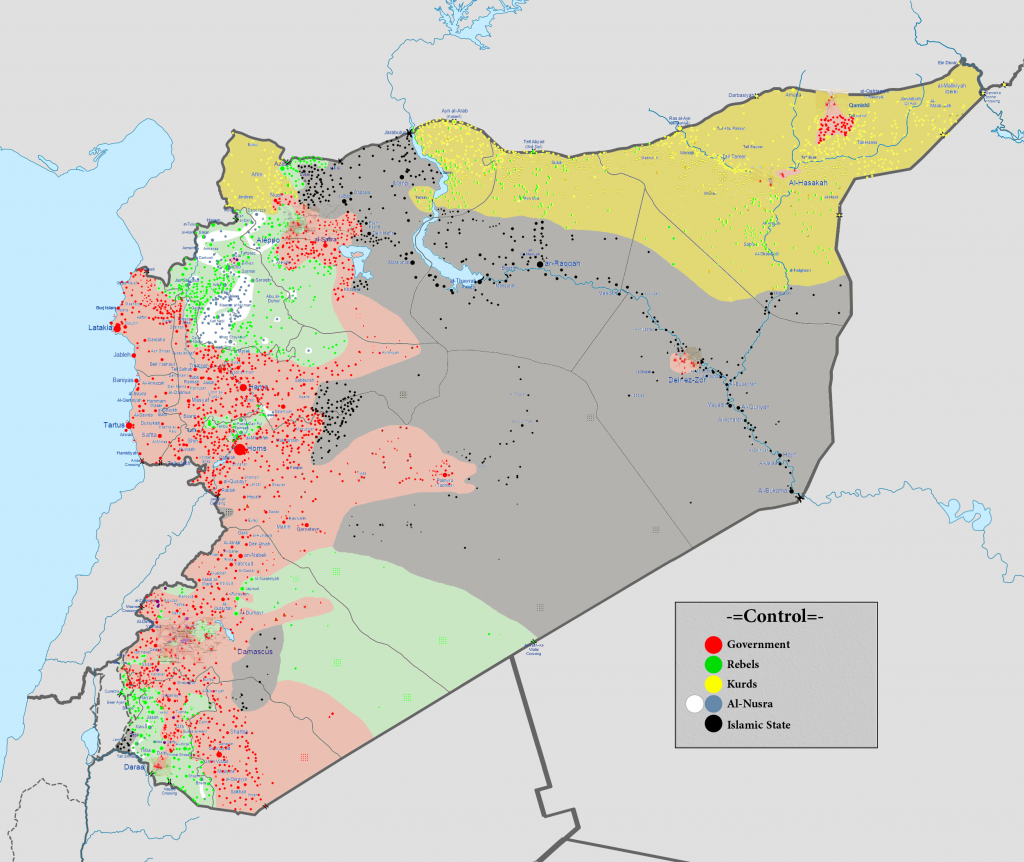

No serious observer, however, believes that Syria can be reconstituted. The Kurds declared an autonomous Federation of Northern Syria (Rojava) in March 2016, and will not surrender this freedom lightly. The Syrian opposition is against a formal partition of Syria, but the option of transforming the country into a federal state is on the table. If the country’s five-year-long civil war continues, interest in partition will likely grow, either as a last resort or recognition of an existing reality. The logical corollary of ceasefire efforts is that a de facto partition will begin to crystallize, as none of the warning parties will agree to govern together or be governed by each other. “We know how to make an omelet from an egg,” observed Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Ya’alon, but “I don’t know how to make an egg from an omelet.”

Any geopolitical settlement that involves redrawing Syria’s borders for the sake of regional security must also rubber-stamp Israel’s control of the Golan for the same purpose. The Heights have now been governed by Jerusalem for over twice as long as Damascus—49 years versus 22. It is time to recognize that change as permanent.

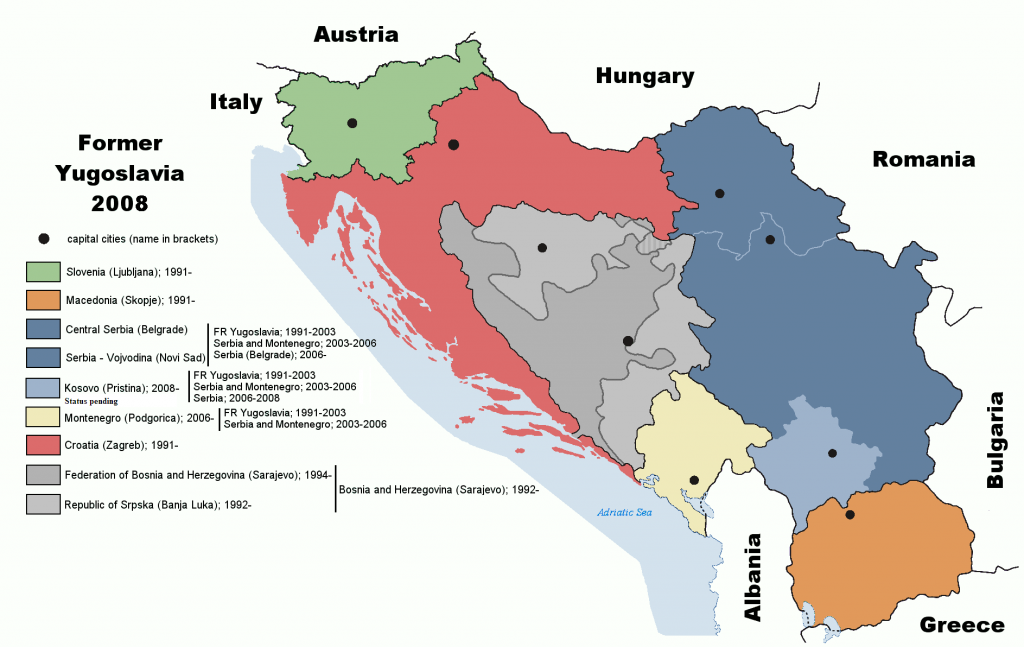

Broadly speaking, there are four key ways in which a state can cease to exist under international law. First, a state can splinter through a series of secessions, leaving behind a rump state that inherits its predecessor’s legal personality. For example, Russia is the recognized legal continuation of the USSR. Second, a state can be ripped apart by internal strife to such an extent that it is deemed to have ceased to exist and no single successor inherits its legal personality. Yugoslavia is an example of this. Third, a state can dissolve itself by agreement. Czechoslovakia, for instance, voted to divide itself out of existence. Fourth, a state can voluntarily merge or be absorbed into another state, as when East Germany dissolved itself when it was united with West Germany.

Syria could plausibly collapse along the lines of the first two possibilities: Secessions could leave a diminished core limping on like post-Soviet Russia; or the secessions could be of such magnitude that the world concludes Syria has ceased to exist, rejecting the claim that a rump Assad-governed enclave is the rightful continuation of Syria. But whatever happens, there will only be a stable border between these entities and Israel if the latter retains permanent control of the Golan Heights.

This Soviet-style scenario could play out as follows: Syria could experience a series of secessions, beginning with ISIS and the Kurds and extending to other rebel groups. If Damascus accedes to these secessions, betting on the survival of Assad’s Alawite minority in a smaller state, the new states’ independence would be universally recognized. In turn, the world could recognize the rump Syria as the legal successor of the old entity, including its continued claim over the Golan Heights. Indeed, the Vienna Convention on State Successions in Respect of Treaties is explicit in stating that “a succession of states as such does not affect a boundary established by treaty,” i.e., the legal instruments that created modern Syria.

Nevertheless, the promotion of new borders for the sake of regional security provides a golden opportunity to take other factors into account.

First, the Golan is vital to Israel’s security: Israel cannot risk the presence of a powerful army or jihadist guerillas along the eastern shores of the Sea of Galilee. This means that Israeli possession of the Golan is vital for regional security, because a war in which the Golan is used against Israel would have regional ramifications. Considering Hezbollah’s heavy involvement in the Syrian war, anything that allows the Iranian proxy to threaten Israeli territory increases the prospects and potential scope of a regional war in which Israel will use force that many will undoubtedly condemn as disproportionate in order to eliminate the threat of incessant rocket attacks on a vulnerable population. Indeed, it appears that Iran is formulating a Plan B for Syria that involves leaving a Hezbollah-style force on the Syrian side of the Golan Heights for the day after Syria ceases to be unitary state. Jerusalem needs to control the Heights in order to minimize this threat.

A Druze man and woman on the Israeli side of the Golan Heights watch the fighting taking place on the Syrian side, June 16, 2015. Photo: Basel Awidat / Flash90

Second, the question of the Golan’s fate needs to be settled in order to prevent future instability. Whatever entities arise east of the Golan need to know that they have no chance of reaching the Sea of Galilee if war is to be prevented. Hezbollah and Iran are likely to invoke Israel’s presence on the Heights as an excuse for further aggression, so the world needs to resolve in advance that it will categorically reject such arguments and treat the Golan border as inviolable.

Third, the residents of the Golan wish to remain part of Israel. Increasing numbers of Golan Druze are taking Israeli citizenship. If other parts of Syria are splintering off because the residents reject being ruled by Damascus, the wishes of the Golan Druze, who have known Israeli rule for 50 years now, should be similarly respected. And that is before addressing the issue of the Israeli Jews living on the Golan. The world claims that the Golan is occupied, but in an ongoing comparative study, Prof. Eugene Kontorovich of Northwestern University Law School has found that the international community has generally been willing to allow settlers to vote in referenda on the fate of occupied territory. Thus, the Baker Plan envisioned Moroccan settlers voting on the fate of Western Sahara and the Annan Plan allowed Turkish settlers in Northern Cyprus to vote on the island’s fate.

If the international community were to follow its own established practice, it might propose a referendum in which all residents of the Golan—Jewish and Druze—could vote to accept Israel’s annexation of the territory. At any rate, this would be far less controversial than actually delivering these Druze into Assad’s hands.

The legal and political cases for recognizing Israel’s control of the Golan Heights have solid historical support.

There are other grounds on which the international community could legally ratify Israel’s control of the Heights. Consider the legal principle of “effectivity,” which was eloquently articulated by the Canadian Supreme Court in its landmark 1998 legal opinion on the possible secession of Quebec. This ruling “proclaims that an illegal act may eventually acquire legal status if, as a matter of empirical fact, it is recognized on the international plane.” Addressing fears that this would encourage illegal activity, the court clarified that “a subsequent condonation of an initially illegal act [does not] retroactively create a legal right to engage in the act in the first place.” This principle gives the world the ability to conclude that, although the initial annexation was illegal, and there is no right to annex occupied territory, the effectiveness of Israel’s policy means that it should receive retroactive approval, especially in light of a fundamental change of circumstances.

It is true that international law considers the crime of aggression to be a violation of jus cogens law, meaning that states must refrain from recognizing its effects. But the Heights were not conquered in an aggressive war, and the Security Council notably rejected the idea that the annexation was aggressive in a Jordanian draft resolution on the issue. Having recently annexed Crimea, even Russia should be open to reconsidering the case for defensive conquest.

Legally and politically, the case for recognizing Israel’s control of the Golan would be solid.

That would cover a Soviet-style collapse, in which Syria splinters but leaves behind an intact core. But should Syria be officially dissolved instead, as was Yugoslavia, by the secession of various regions, a radically new legal and political reality would be created.

Consider the following scenario: If Syria experiences multiple secessions, which might include the Assad regime fleeing Damascus in favor of a coastal Alawite state, it is possible that no new state would comprise a majority of Syria’s territory or population. In this case, the world powers might declare that Syria has ceased to exist and refuse to recognize any of the successor states emerging from the rubble as the inheritor of Syria’s legal personality. “Extinction is not effected by…prolonged anarchy within the State,” explained Justice James Crawford of the International Court of Justice, “provided that the original organs of the State…retain at least some semblance of control.” Syria could soon conclusively fail to meet that test.

After the Yugoslavian civil war erupted, it became clear that the country could not be reconstituted. The Badinter Arbitration Commission judged in 1991 that “Yugoslavia is in the process of dissolution.” Then, in 1992, the Security Council decreed in Resolution 777 that “the state formerly known as the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia has ceased to exist” and stated that the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, later known as Serbia and Montenegro, could not “continue automatically” Yugoslavia’s membership in the UN. The FRY’s claim to be Yugoslavia was widely disputed, since it did not contain a majority of its predecessor’s population or territory. In a subsequent treaty, the five successor states agreed to divide between them the former Yugoslavia’s rights and assets as sovereign equals.

Seven independent states and more autonomous regions eventually emerged from the former Yugoslavia. Photo: Wikimedia

Yugoslavia dissolved despite the survival of its federal territories. The judgment that such a state in effect longer exists would be even stronger in the case of a unitary state collapsing along battle lines rather than internal boundaries, as Syria is doing now. In effect, no new state would have a strong claim to “be” Syria, and the world powers could declare that it has been extinguished with no single successor.

This would create a curious paradox or lacuna—a gap in the law. In effect, standing international resolutions would be demanding that Israel return territory to a state that no longer exists. Crucially, since none of the successor states would automatically inherit Syria’s rights and assets, none would inherit a prior legal right to the Golan Heights. Israel would have a prima facie obligation to hand over the territory, but no state in the world would have a legal claim to receive it. What would happen then?

The answer is that nobody knows. Syria’s successor states would have to justify their existence on the basis of the territories they control at the end of hostilities. They could not claim territory outside their effective control. This provides a unique window in which Israel’s claim to the Golan could be recognized with reference to its actual possession of the territory.

Nobody knows what would happen if a successor state to Syria tried to claim the Golan – though it surely wouldn’t be resolved easily.

Such a situation would be almost unprecedented. It would be the first dissolution of a unitary, rather than federal, state in modern history, with one ironic exception—Palestine. When Mandatory Palestine collapsed into internecine warfare in 1948, the world recognized Israel’s boundaries not with reference to the 1947 UN Partition Plan, which was never implemented, but Israel’s actual possession of territory at the end of hostilities. It is true that claims to the territory by invading third parties were not recognized, namely Transjordan’s claim over the West Bank, but the ambiguity created by the unresolved question of sovereignty over this territory haunts the world to this day and remains a source of instability. By recognizing Israel’s control of the Golan, the world can prevent the emergence of another such anomaly that will only be a source of future grief.

The purpose of international law is to protect the international order, one in which states exist within secure and recognized borders. When the law provides no clear answers, it should be interpreted in the spirit of bolstering this international order. If the international community wishes to do this, nothing can legally stop it. The only way to bolster this international order and resolve the open question of the Golan is to recognize Israeli control over the territory.

From the Israeli perspective, this is obvious. Realistically speaking, there is no longer any incentive for Israel to return the Heights to Damascus. Until recently, some in Israel hoped to offer the Golan in order to seduce Syria away from the Iranian axis, a bold gamble to thwart Tehran’s push for regional hegemony. But with Iran emboldened by the recent nuclear deal and Syria now firmly under its domination, that possibility is foreclosed.

Israeli soldiers examine a fire caused by missiles fired from Syria that hit open areas in the Golan Heights, August 20, 2015. Photo: Basel Awidat / Flash90

The process by which the world might recognize Israeli sovereignty over the Heights, however, will not be easy. The world needs not wait until the official collapse of Syria, but these scenarios may still be a way off, as the world powers resist recognizing the inevitable. Iran and Russia have every interest in maximizing Assad’s control over Syria, and would only write off the country as an absolute last resort. Recognizing breakaway states would raise uncomfortable questions about what is to be done about ISIS. And the current areas of control by various parties to the Syrian civil war do not neatly divide into separate, coherent entities that could be viable states.

But as surrounding states collapse further into a war of all against all, international recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the Golan would be a bold statement in defense of the international order. Should the world fail to make such a statement, the Middle East could yet pay a heavy price for the world’s failure to let an anachronistic policy fall into desuetude.

![]()

Banner Photo: Mendy Hechtman / Flash90