The deal with Iran was widely celebrated as a move to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons around the world. Early signs suggest it might do the exact opposite.

Deep in the weeds of discussions about the nuclear deal with Iran, which usually focus on whether the price paid in sanctions relief and international legitimacy is sufficiently worth the hoped-for forestallment of an Iran nuclear bomb, one issue has been largely overlooked: the effect this deal is likely to have on the broader nonproliferation regime, with the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) as its centerpiece. In the wake of what is known formally as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), reached last July 14 between the six leading world powers (known as the P5+1, representing the five permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany) on the one hand, and the Islamic Republic of Iran on the other, crucial requirements for effective nonproliferation have been brushed aside and are in danger of being ignored down the road.

The NPT came into force in 1970, setting a global standard for putting a stop to the spread of nuclear weapons and the destabilization that could result. The framers of the JCPOA recognized the importance of the NPT when they included in Article XI of the agreement’s “preamble and general provisions” the stipulation that the JCPOA “should not be considered as setting precedents for any other state or for fundamental principles of international law and the rights and obligations under the NPT….”

Yet despite that disclaimer, in the months since the announcement of the JCPOA, it has become apparent that one of the very pertinent questions regarding the Iran deal is just that: the implications of the agreement for nuclear nonproliferation principles, norms, and standards in the future. The JCPOA has set, and is in the process of further establishing, some new standards for Iran in the nuclear realm that will inevitably affect the nonproliferation regime and the attitudes of other states toward their own nonproliferation requirements and commitments.

Instead of shoring up the nonproliferation regime, the Iran deal is likely to dangerously undermine it.

Indeed, a careful look at the standards established by the JCPOA, as well as the reactions of the great powers to Iranian behavior in the months that have passed since it was announced, reveals that instead of shoring up the nonproliferation regime, the Iran deal is likely to dangerously undermine it. At issue are three important questions that are central to the long-term effectiveness of the NPT: the right of non-nuclear weapons states that are members of the NPT to work on the fuel cycle (uranium enrichment); the nature and intrusiveness of International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspections of facilities—nuclear and other—especially in states that are suspected of having violated the terms of the NPT by working on a military capability; and the consequences for states that are found to have violated the terms of the NPT.

The JCPOA has been hailed as a historic, transformative moment—and it may well be so, but not necessarily for the reasons its proponents have given. Whether it succeeds in helping turn Iran itself into a more productive member of the international community—a “successful regional power,” as President Obama put it—is at best debatable. What seems clear, however, is that the deal has introduced cracks in the pillars on which the world’s relatively nuclear-weapons-free history have stood.

At the time the NPT was negotiated, there were five declared nuclear states—the United States, the Soviet Union, Great Britain, France and China—and fears were aroused that another significant group of states would be capable of moving to nuclear weapons in a short period of time. The states of concern at the time did not raise alarms as far as their overall international behavior—states like Sweden, West Germany, and Japan—and the thinking was that the treaty would mitigate their motivation to cross the nuclear threshold by reassuring them that no one else would do so either. To that end, a collective security regime would be formed to the benefit of all; countries that remained without the weapons would be helped in benefiting from civilian nuclear energy, and those that had nuclear weapons made a commitment to work towards their own disarmament.

The logic of the treaty was sound at the time. However, what it did not anticipate was that states would challenge the NPT from within: namely, join the NPT and then proceed to abuse its terms in order to advance a military nuclear capability under the cover of a supposedly civilian one. But that is what began to happen in the 1970s, in Iraq, Iran, Libya, and North Korea. These new proliferators also were considered dangerous in terms of their international behavior and aims. Article IV of the NPT—which gave non-nuclear-weapons states the right to a civilian nuclear program—was particularly vulnerable to abuse by these regimes.

In the face of the challenge from these new and determined proliferators, it became clear that the nonproliferation standards that were established with the NPT needed to be safeguarded and further enhanced for the treaty to remain viable over the long term. Iraq’s nuclear weapons program—revealed in the wake of the 1991 Gulf War—led to the conclusion of what became known as the Additional Protocol, adding another level of safeguards and inspections.

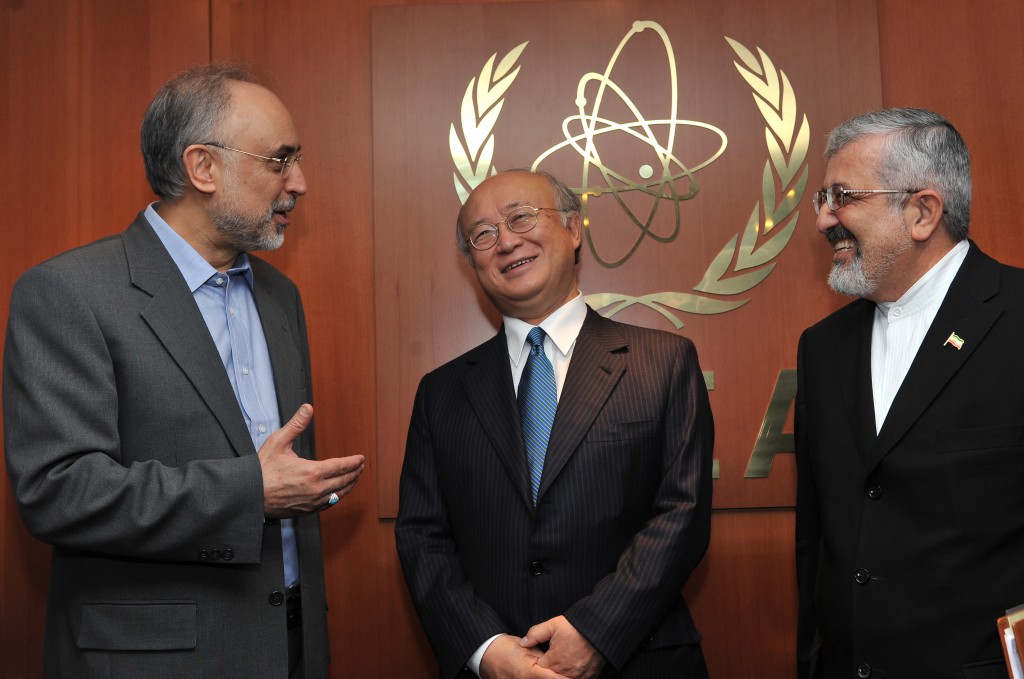

Ali Akbar Salehi, president of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, speaks at the International Atomic Energy Agency General Conference, September 16, 2013. Photo: Dean Calma / IAEA / flickr

Iran was one of the very early states to join the NPT, making a clear commitment not to work on nuclear weapons. Nevertheless, it began violating that commitment by secretly beginning work on a military nuclear program during the mid- to late-1980s. The challenge posed by Iran did not fully come into the international spotlight until 2002, however, when the construction of two undeclared nuclear facilities, at Natanz and Arak, was revealed. Negotiations from 2003 until the JCPOA was announced in July 2015, which took place for the most part in parallel to failing international efforts to prevent North Korea from achieving nuclear weapons status, were focused on bringing Iran back into the fold of the NPT. Any nuclear deal to be concluded with Iran was clearly meant to uphold nonproliferation standards, and especially to ensure that Iran—a state guilty of repeated violations and deception—would not be allowed to get away with abusing loopholes in the NPT, thus undermining the nonproliferation regime.

But that goal is not being served by the JCPOA. To the contrary, the agreement’s provisions raise serious questions about the nonproliferation approach and policies of the influential international actors that negotiated the deal with Iran.

The most striking nonproliferation precedent established by the JCPOA regards Iran’s uranium enrichment program. The seeds of the problem were planted in the NPT, which does not prohibit states from enriching uranium in the context of a legitimate civilian nuclear program. The problem is that uranium enrichment involves what is called “dual-use technology,” meaning that the same centrifuge-based methods that are used to enrich uranium to low levels (3.5-5 percent), in order to produce fuel for reactors as part of a civilian nuclear program, can also be used to further enrich the uranium to high levels (over 90 percent), in order to produce fissile material for a nuclear weapon. Mastering the technology for uranium enrichment proved to be no easy task for Iran, and its work in this regard troubled the international community due to suspicions that a terror-supporting and hegemony-oriented Iran was working in parallel on nuclear weapons.

As such, throughout the twelve years of diplomatic efforts to stop Iran in the nuclear realm, the suspicion that Iran was abusing a purportedly civilian enrichment program for military purposes was uppermost in the minds of the international negotiators. For this reason, all the UN Security Council resolutions against Iran between 2006 and 2010 demanded that Iran suspend uranium enrichment. Iran refused to comply. In addition to building up its stockpiles of low- and medium-enriched uranium, Iran worked to develop much more powerful centrifuges that would be able to enrich uranium as much as 20 times faster than older models.

While international concern grew, Iran was establishing facts on the ground that would be increasingly difficult to undo.

While international concern grew, Iran was establishing facts on the ground that would be increasingly difficult to undo—from R&D to the installation of centrifuges to the continued enrichment of uranium, as well as work on a separate, plutonium-based program and the development of ballistic missiles that could deliver nuclear warheads. Iran’s gamble proved effective: By the time the P5+1 began their more serious round of negotiations with Iran in late 2013, Iran’s advances were so significant that a growing consensus emerged that the international negotiators could no longer expect Iran to completely dismantle its infrastructure. While not happy with the situation, they assessed that they would have no choice but to leave Iran with some enrichment capabilities. In the face of criticism, the P5+1 insisted that they would only allow Iran a very limited, virtually symbolic program of no more than 1,500 centrifuges at most.

However, once negotiations on a comprehensive deal began in early 2014, the P5+1 began conceding to Iran on this front, and according to details that appeared in the media over the months of negotiations, the P5+1 states were signaling their willingness to leave Iran with ever-growing numbers of centrifuges. The final deal confirmed that the reports were accurate—the deal ultimately left Iran with around 6,000 working centrifuges and a provision that enabled it to continue research and development on an entire range of advanced-generation centrifuge models. Moreover, President Obama assured Iran that it would be able to expand to a full enrichment program once the deal sunsets (in 10 to 15 years), allowing Iran to become a “normal” member of the NPT once again.

The combined effect of these messages was to legitimize Iran’s uranium enrichment program, even though Iran had violated the NPT and lied about its intentions for decades. Legitimizing Iran’s enrichment program also stood in stark contrast to earlier U.S. efforts to prevent other states that were seeking civilian nuclear cooperation from working on the fuel cycle. Indeed, recognizing the problematic loophole created by the NPT, the United States established a most welcome “gold standard” for civilian nuclear cooperation: requiring states that sought such cooperation to forswear uranium enrichment and to rely instead on purchasing fuel on the open market. A case in point was the United Arab Emirates, held to the gold standard in a deal concluded with the U.S. in 2009. Unsurprisingly, not long after the JCPOA was announced, the UAE—a member in good standing of the NPT—announced that it no longer viewed itself to be bound by the gold standard regarding uranium enrichment.

With the control of the fuel cycle compromised, one would expect that verification and inspections of Iran’s nuclear activities would be significantly strengthened in the JCPOA. And indeed, because of Iran’s history of deception, the P5+1 negotiators issued statements from the start of the negotiation with Iran that a comprehensive and final deal would critically depend on inclusion of a robust verification regime, with intrusive rights of inspection for the IAEA at any suspicious facility in Iran. Yet the Iran deal ultimately came up short in this respect as well.

The verification regime spelled out in the JCPOA raises some important questions about how inspections at suspicious facilities in Iran could actually be carried out in the coming years. The JCPOA does not provide clear instructions; in fact, the text of the deal is dangerously murky on this issue. Two questions in particular deserve attention.

The first regards the principle of “managed access” to suspicious facilities. Managed access is a non-specific term that must be explained, and this leaves the field open for different interpretations. Rather than specifying that in light of Iran’s past deception and loss of trust, the international community must have a mandate to inspect suspicious facilities in Iran “anywhere, anytime,” the P5+1 negotiators were content with this ambiguous formulation. What this means, in practice, is that Iran will have a decisive say on not only when a site can be entered, but whether it can be inspected at all—crippling the most important means of guaranteeing the effectiveness of verification.

The first event that tested Iran’s interpretation of managed access was the inspection of the military facility at Parchin over this past summer, in the context of the IAEA’s investigation of Iran’s past weaponization work. Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, had already made it quite clear over the months of negotiations with the P5+1 that Iran would never allow inspectors entry into its military facilities, and he and various military leaders reiterated this message when the JCPOA was announced, and in the aftermath of the deal. What happened in the Parchin inspection, it emerged, was that Iran collected soil samples from within the facility, while IAEA cameras monitored the process from outside. From Iran’s perspective, this was “managed access,” and it was clearly setting a precedent for future cases—this was the closest that Iran would allow the IAEA to get to inspecting suspicious military facilities. No less importantly, the inspection took place after years of Iranian stonewalling of IAEA requests: As satellite imagery showed, the long-awaited inspection happened only after the Iranians had carried out massive clean-up operations at the facility.

And indeed, timing of inspections is a crucial problem in the precedents set by the JCPOA’s verification regime. The terms of a prospective inspection at a suspicious facility are formulated in the JCPOA in a manner that in effect enables Iran to delay IAEA entrance for 24 days—24 days, in other words, that Iran could use to clean up evidence of wrongdoing. In truth, the text of the JCPOA is even more problematic because the 24-day count begins only when the IAEA has submitted its request for access to the site. But there is a prior stage that is noted in the text of the deal according to which the IAEA must present its incriminating evidence to Iran, and wait for Iran’s initial response. There is no time limit specified for Iran’s response, and on the basis of Iran’s practice of foot-dragging in the past, it could easily stretch this out for days, and perhaps even weeks, if not longer.

These problems of verification weaken the ability to effectively monitor Iran’s nuclear program, but there are also implications for other cases. There is no reason to expect that in dealing with future violators of the NPT, these states will not refer back to the JCPOA as a benchmark for verification. If Iran doesn’t have to open military facilities or allow snap inspections, why should anyone else? As such, the JCPOA actually creates a new loophole. If a state wants to build a military nuclear capability in violation of the NPT, but wants to fool the international community and remain within the treaty, the place to build such a program would obviously be at a military site.

Finally, we come to the issue of the consequences for a state that violates the NPT. While the architects of the NPT in the late 1960s did not anticipate that states would join the treaty and then proceed to violate it, it is by now clear that some states have chosen this path, and others are likely to follow. The case of North Korea is particularly instructive in this regard. Those who believed in the early 1990s that it was a mistake to insist on revealing the extent of North Korea’s past violations, and that negotiations at the time should focus solely on conditions for future compliance, woke up in the new millennium to North Korea having crossed the nuclear threshold. North Korea is a stark and undisputed nonproliferation failure. As such, the consequences for violations must be clear, stiff, and reliable. Violators must be made to “come clean” as a condition for lifting sanctions and other forms of pressure, as well as for reaping the treaty’s benefits. Potential violators must understand that the costs to a regime’s long-term status, wealth, and power would far outweigh the benefits of developing such a weapon.

And yet, the JCPOA projected a very different message. From the start of the final round of negotiations with Iran, which began in earnest in late 2013, the P5+1 clearly positioned themselves in charge of the negotiation and of carving out a comprehensive and final deal with Iran. But from the beginning there was one issue on which they were they were not taking full responsibility: the investigation into Iran’s past nuclear weapons work, grouped together by the IAEA into 12 broad topics under the title of the “Possible Military Dimensions” (PMD) of Iran’s nuclear program.

The PMD investigation was delegated by the P5+1 states to the IAEA; nevertheless, provisions in the deal ultimately curtailed the ability of the IAEA to conduct this investigation effectively. The P5+1 not only set a short timeline for submitting the final IAEA report on Iran’s past work, at only five months after the deal was concluded; they also clarified that the deal would be implemented regardless of the content of this report. In other words, there were to be no consequences to past Iranian violations.

It soon became clear that the deal would be implemented regardless of the IAEA’s report. This had predictable consequences.

The predictable result of this was that the P5+1 placed their political interests—the desire to reach a deal—above the IAEA inspections process as far as the chain of authority. But rather than using that authority as a means to force Iran to provide the best answers to the IAEA and in a timely manner, they left the IAEA to fend for itself in an unrealistic timeframe, and without the necessary leverage to force Iran to provide full responses to its queries, because the deal would be implemented regardless. In effect, the P5+1 used their authority in a manner that not only did not enhance the mandate of the IAEA, but actually undermined it by imposing political constraints, and signaling that they were not going to make an issue of Iran’s past violations of the NPT. If the original goal of the P5+1 negotiators was to carve out a deal that would impose stricter standards for Iran because of its deceptive past behavior, in the end it turned into a cover for more lenient interpretations both of Iran’s past behavior and some key future requirements.

What happened in December 2015 underscored that the PMD issue was being brushed aside by the P5+1, despite the incriminating findings that the IAEA was able to conclude even under tight constraints. In early December, IAEA Director-General Yukiya Amano presented his final report, which included the assessment that Iran had worked on a military nuclear program in a coordinated effort up to 2003, and in a less coordinated fashion up until 2009—flatly contradicting Iran’s denials. Significantly, he also noted that there were gaps in Iran’s cooperation with the IAEA investigation. A report issued by the Institute for Science and International Security on December 8 includes a comprehensive description and analysis of Iran’s limited responses to the 12 outstanding questions on PMD. The authors of the report note that “Iran’s answers and explanations…were, at best, partial, but overall, obfuscating and stonewalling.” Amano’s own conclusion contained a hint that if Iran had cooperated fully with the investigation, the results would likely have been even more incriminating.

And yet, on December 15, in the wake of Amano’s report, and following a draft resolution for closing the PMD file that was submitted a week earlier by the P5+1 to the IAEA Board of Governors, the board accepted the draft resolution and closed the PMD file. This result was the final proof, if more was needed, that the P5+1 states were not interested in either exposing or drawing implications from Iran’s past work on a military nuclear program. Iran was let off the hook, and no one challenged the Iranians when they issued statements after the decision, saying that the “fabricated” case of the PMD was finally off the table. For Iran—and implicitly for the P5+1 as well—the Iranian narrative of having done no wrong in the nuclear realm became a matter of record.

Ali Akbar Salehi meets with IAEA Director-General Yukiya Amano at the IAEA’s headquarters in Vienna. Photo: Dean Calma / IAEA / flickr

Where does this leave the investigation? Some believe that it will continue, but that would depend on political will to confront Iran, which is currently nowhere to be found. More importantly, there is no longer leverage on Iran to cooperate, even if the P5+1 were inclined to request it to do so. This is very likely the final word on the PMD, at least for the foreseeable future. The JCPOA ordeal has taught us that confronting NPT violations is a political, not a technical process. There are no treaty-based guidelines that supersede political decisions, and everything turns on a political determination to extract the necessary concessions from the state suspected of seeking nuclear weapons.

At the end of the day, the global nonproliferation system depends, above all else, on the manifest will of the international community, and especially the permanent members of the UN Security Council, to maintain it. That important nonproliferation principles and standards have been seriously compromised in the framework of the JCPOA raises important questions about the fundamental commitment of these strong international actors to uphold nonproliferation standards over the long term. The problem is especially acute when the proliferator is not only dangerously challenging the NPT from within, but also is openly threatening neighboring states as well.

Unfortunately, there are other indicators that P5+1 commitment to nonproliferation has been weakened with respect to Iran. The most dramatic example has been the handling of its development of ballistic missiles, including long-range missiles that can carry nuclear payloads. These missiles are clearly relevant to a nuclear weapons capability, and yet they were kept purposefully outside the purview of the negotiations on the JCPOA, at Iran’s behest.

Iran’s missile tests in October and November 2015—in flagrant violation of UN Security Council Resolution 1929 from June 2010, but not of the JCPOA—raise a further complication arising from the Iran case: the lack of congruity between provisions in the Iran deal and restrictions in relevant UN Security Council Resolutions that have a bearing on a military nuclear capability. With respect to ballistic missiles, the instructions in the two documents are not in sync, and thus a question arises as to which norm is to be followed. Granting priority to the Iran deal over UN Security Council resolutions—as reflected in the P5+1 reaction to Iran’s missile tests, which took pains to note that the tests did not violate the deal—is confusing and problematic. This could very well set a negative precedent for understanding the chain of authority for nonproliferation standards in future cases as well.

At this time, Iran has suffered no consequences for its ballistic missile violations; given its repeated declaration that new sanctions would constitute a material breach of the JCPOA, it’s unlikely that it will in the near future.

Important principles and standards have been seriously compromised in the framework of the JCPOA, raising important questions about the commitment of international powers to uphold nonproliferation standards over the long term.

All the provisions that were agreed to in the JCPOA were for a regime that has been deemed to have violated the NPT by working on a military nuclear program—a regime that denies all charges, and that is most likely still determined to achieve nuclear threshold status if not nuclear weapons. This means that a known cheater, which continues to deceive, was granted terms in the deal that not only do not fully address the added proliferation concerns that arise in this case, but that in some respects are better than what other states are offered, even though the latter are members of the NPT in good standing. The IAEA final report on the PMD and the subsequent Board of Governors decision make a mockery of all the statements issued over the years that required Iran to cooperate fully with the IAEA and with Security Council resolutions. It is a serious blow to the NPT.

Other NPT member states—especially those in the Middle East—are already watching developments closely, and will no doubt continue to do so as the Iran case unfolds. These states will be reacting to the standards that have been carved out for Iran, and will regard them as creating new precedents in the field of nonproliferation whether the P5+1 meant for this to happen or not, as seen in the case of the UAE.

Can nonproliferation standards be upheld via a diplomatic process when challenged by a very determined nuclear proliferator? Clearly this is not impossible, as the case of Libya underscores. Libya decided to give up its nuclear program, along with other weapons of mass destruction, in December 2003 after the pressure of years of sanctions—but also because it believed that it might be the target of a possible U.S. military assault. Massive pressure seems to be the essential key to successful bargaining with a determined proliferator that is undermining the NPT, and is especially effective when the international negotiators are intent on using that pressure as leverage at the bargaining table. But if the negotiators are not willing to push all levers of pressure, and to call the proliferator’s bluff when it threatens to walk, the result is inevitably something like the JCPOA: a deal that not only fails to ensure that Iran will remain non-nuclear, but dangerously relaxes nonproliferation standards established 45 years ago.

Gas centrifuges for uranium enrichment were seized from a ship bound for Libya in 2003 and taken to the United States. Photo: U.S. Department of Energy / Wikimedia

Further questions have been raised regarding the U.S. administration’s actual intentions in negotiating the JCPOA. As a major architect of the NPT, and the lead P5+1 negotiator, the position of the U.S. in this regard is very important. Over the course of the talks, however, questions were repeatedly raised about whether the U.S. was hoping to halt Iran’s nuclear program but would ultimately accept a policy of containment if it failed, or whether the goal was unequivocally prevention. Was the United States trying just to delay Iran’s program and gain time (as the sunset clause suggests), or did it mean to prevent Iran from ever building a nuclear weapon by dismantling its nuclear infrastructure, as originally claimed? And how did the evolving U.S. approach square with the logic of the NPT, which is certainly geared to stemming proliferation for good, without a timeline? When President Obama insisted last April that “Iran will not get a nuclear weapon on my watch,” did he mean to imply, as many suggested at the time, that further down the road an Iranian nuclear bomb was something we might have to learn to live with?

These are not easy questions, and while the answers are not yet clear (and might never be) they have serious ramifications for the nuclear nonproliferation regime. The very fact that they were raised at all means that there was a sense that nonproliferation standards might be in the process of being relaxed for Iran in order to secure a deal. This runs counter not only to the NPT, but to firm statements issued by the administration itself when the deal was presented, claiming that it met all of its objectives in stopping Iran. But what were the objectives, and what was actually achieved? Does the deal stop Iran from ever acquiring a nuclear weapon, or only delay this outcome? Does Washington recognize the holes in the deal, is it ignoring them, or does it believe they are not important, or perhaps less important than being able to present a deal?

These questions are left to be addressed by the United States; for the sake of the continued health of the nonproliferation regime, U.S. positions should be clarified in relation to the Iran deal, and in light of the criticism that has been leveled against it. What hangs in the balance is the very heart of half a century of global efforts to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons, and the possibility of a new nuclear arms race—which could engender a new nuclear equation in the Middle East that will be far more complex than that of the Cold War.

![]()

Banner Photo: U.S. Department of State / Wikimedia