Outside of Israel, learning Hebrew can be a ritual slog. A better way to teach an old-new language can be found where it is spoken—and reinvigorated—every day.

When I first moved to Tel Aviv, I thought I would learn Hebrew effortlessly. My family and friends agreed. Mere months after my arrival, they would ask me over the phone if I was fluent yet. It’s now two years later, and I’m not sure “fluent yet” will ever happen. After numerous Hebrew courses and self-inflicted, self-designed homework assignments, my Hebrew is in a place I never dreamed it would be. But somehow, the further I progress, the more it seems that fluency, true fluency, is still far off. Even now, while I can use my Hebrew to competently socialize, read a short story, watch a TV show, and argue with my cell phone provider about my bill, I sometimes find myself lost within a sentence and unsure of the word I need.

Language is both the most frustrating and the most rewarding aspect of living in Israel. Of course, being a non-native speaker makes life more difficult, but learning a language is fun for me. I haven’t had much success in the past with the acquisition of technical skills. My guitar lessons went nowhere. I failed high school French. I gave up on my online Sign Language course. And, after a brief stint trying to learn wood-working, I gave my father a very rickety end-table and hung up my safety goggles.

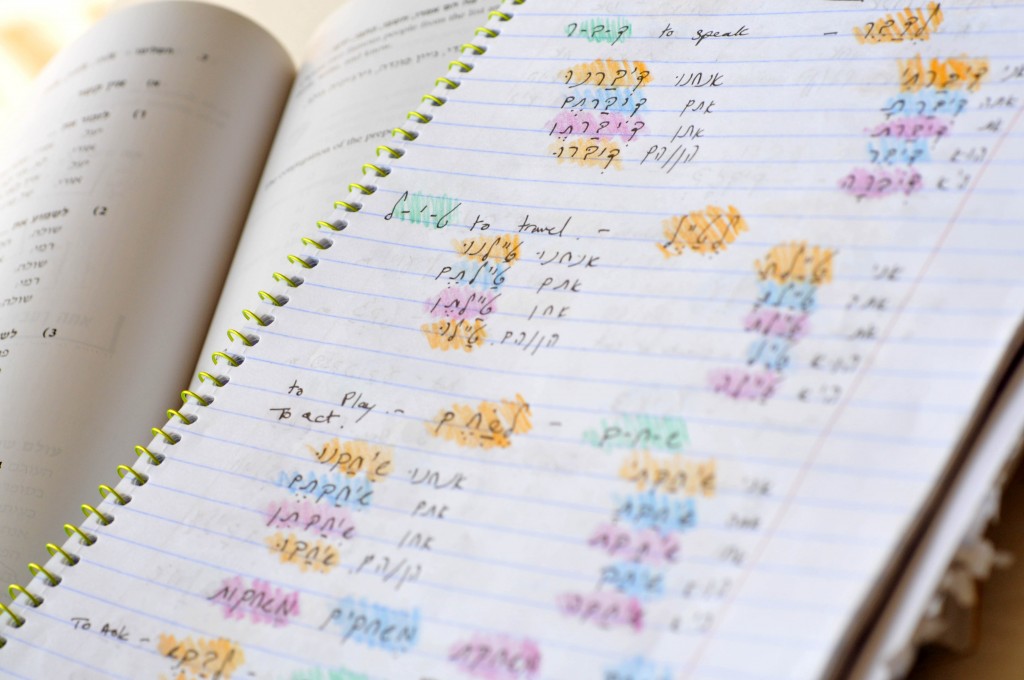

But with Hebrew I simply kept going. I finished one intensive ulpan—the state-sponsored Hebrew course for all new immigrants—at Tel Aviv University and then signed up for another, at Ulpan Bayit in Tel Aviv’s Florentin neighborhood. I progressed past the beginner level, which is in itself an amazing feeling. Even though I see clearly how far there is to go, I have a sense that I’m making progress.

Tel Aviv, it should be noted, is not the ideal environment for intensive Hebrew study. The high number of English speakers and English-speaking Israelis make immersion nearly impossible. And while I thought I would learn Hebrew the way an infant learns, by simple exposure, this turned out to be little more than a fantasy. Until you have progressed to a certain level, most Israelis prefer to speak English with you. The reason is simple: their English is better than most Americans’ Hebrew.

There is also the issue of the Anglo Bubble—the community of European, American, Australian, and South African English speakers in Tel Aviv. They tend to coalesce together, building a small world in which Hebrew, quite frankly, is not really necessary.

I arrived in the very heart of this Bubble when I came to Tel Aviv. I found myself working as a preschool teacher. In New York, I had worked at a Jewish preschool in lower Manhattan. In Tel Aviv, I was working at an international English-only preschool. The families came from a mix of backgrounds. Most consisted of an Israeli father and a mother from somewhere else. A smaller group was made up of embassy workers. The smallest minority of all was composed of families with two Israeli parents who disliked the public preschool options or were interested in giving their children a good foundation in English.

Working in this environment, it was sometimes possible to forget that I was in Israel at all. Ordering a coffee in the morning became the one Hebrew activity of my day. Naturally I made friends with my co-workers and the process of entering the Anglo Bubble began. The problem was that I didn’t like the Bubble. I’ve met plenty of anti-Israel people before in my life. But here was a group that, fascinatingly, was anti-Israel in a way that had nothing to do with politics. They espoused the ubiquitous diaspora opinion that they “love Israel but hate Israelis.” To them, speaking Hebrew or even letting their children learn it meant admitting that they are in Israel and not London or New York, where they wish they were. This, needless to say, was not what I wanted for myself.

Yaron was my teacher at Ulpan Bayit (“home ulpan”) back when it was actually run out of his home. Now he has moved both home and ulpan into two adjacent lofts on Frenkel Street in the so-hip-it’s-passé neighborhood of Florentine. He is now officially a friend rather than a teacher, and one of my favorite people to speak with in Hebrew. An ulpan teacher always knows how to speak to someone so they can understand, whatever their level of Hebrew might be. It’s a real gift.

I sat down with Yaron because I want to ask him when people usually succeed in leaving the English bubble. After all, he sees a lot of students in his ulpan and gets to know them personally. He understands their motives for studying, whether they want to become fluent or just learn a few phrases.

“Six years,” Yaron says. “Six is the magic number. When someone is in Israel that long, that’s when they start to see the value of studying Hebrew seriously.”

I ask him why it takes so long.

“At that point you might have an Israeli partner,” he says. “Or you might want to advance in your career beyond entry level.” Basically, after six years the vacation is over and the limitations of not being a Hebrew speaker become overwhelming. “You might be able to communicate with your partner in English but you won’t be able to participate in a loud, Hebrew Friday night dinner with his family.”

He then asks me if I will be staying in Israel forever. It’s a question you get a lot when you live here, as if everyone is supposed to have “forever” written in their datebook. I shrug and say I don’t know, but then I give voice to a thought that comes to me from time to time. “I can’t leave until I’ve truly mastered Hebrew,” I say. “When I’m fluent, then I’ll go back home.”

“Muzar,” Yaron says. “Strange.”

Of course, I realize this is a strange thought. Learning Hebrew should make living in Israel easier. Why leave after I’ve learned it? The reasons are related to the bigger question of what Hebrew means in the diaspora, and what it means to speak a language for non-practical reasons.

I believe this is something people once understood implicitly. Latin, for example, was studied as an academic language without any other practical application. But in the past 100 years, education in general has become more focused on practicality and utility. This has deeply affected our culture’s view of language. Learning a language is no longer seen as an inherently valuable activity. Instead, a language is considered valuable in proportion to how many people in the world speak it. By this rationale, Chinese and Spanish are worthwhile languages to learn, while French, Latin, and Hebrew are niche languages. One should only learn them if one plans to spend a great deal of time working in a Francophone country, studying Latin texts, or being a rabbi.

I am not criticizing this view of languages. People should consider utility when deciding which language to learn. But we are quick to forget that language is more than just a means of communication.

Sitting with Yaron, I mention one friend I know who has labeled everything in her home with its Hebrew name. The table is labeled “shulchan” and the couch is labeled “sapa.” Yaron laughs. “Most people think that a language is words,” he says. “They think, ‘If I learn the words I will know the language.’ But of course a language is a game. The words are the cards you play with, but the rules of the game are what’s important.”

Yaron, in addition to being a language teacher, is a student of linguistics at Tel Aviv University. Undoubtedly, this makes for a unique approach to studying at his ulpan. “All of Level Aleph (level one) is a game,” Yaron says. He’s referring obliquely to Wittgenstein’s philosophical concept of language-games—substructures of language that demonstrate, in Wittgenstein’s terminology, “the speaking of language is part of an activity or form of life.”

Is it valuable for diaspora Jews to know Hebrew? Yaron thinks about it for a moment. “If you really want to understand Israelis and Israel, you need to know Hebrew,” he says. “For one thing, it is a very different experience to read about Israel in English versus Hebrew.”

This is true. Most Israeli newspapers appear in English, but they all publish different material for their Hebrew editions. The English versions tend to focus on issues that a diaspora audience cares about—diplomacy, defense, Jewish world news, and the peace process. The Hebrew edition, on the other hand, reports on culture, food, events, and aspects of politics that a diaspora audience might not even know about.

But this is still a purely practical reason to learn Hebrew. It’s not the answer I’m looking for.

In the 1960s, the Vatican II council was set up to address how the Catholic Church should relate to the modern world. One of the major changes the council enacted was to give churches permission to deliver the Mass in the language of the local population rather than Latin.

One can see this as part of the general intellectual trend of reducing language to practical application. After all, if a language is not understood, it is not functioning. Therefore, goes the argument, the Mass should be delivered so it can be understood by the congregation.

Like Latin, Hebrew is also a religious language. When I was growing up, I even felt jealous of Christian friends because their religion was in English. Like most Jewish families in my town, we went to synagogue a handful of times over the course of the year. I attended a Hebrew school where I learned to read Hebrew letters and say Hebrew blessings, but not how to understand Hebrew in any meaningful way.

This meant that as a child I was, quite frankly, bored in synagogue. Whether this would have been different had the services been in English is impossible to say. But I do know that I would have been thankful for a Vatican II-esque decision to practice Judaism only in the vernacular.

Little did I know that, in many synagogues and temples across America, this is what has happened. Like the Roman Catholic Church, many Jewish communities are beginning to operate almost exclusively in the vernacular language of their congregations. It is easy enough to see the advantage of this—people can understand the services without having to learn an entire language that may never be of any other use to them. What is lost is slightly less tangible. Whereas a Jew could once feel comfortable in any synagogue anywhere in the world, now he or she will only feel comfortable in synagogues that speak his language. The same goes for the Catholic abroad. A shared language is a way in which a global community can remain cohesive, even if the members only know the words by rote.

This focus on the utility of languages reminds me of certain educators I have worked with who denigrate Dr. Seuss for his use of made-up words. They argue that it teaches children incorrect English. This attitude, which emphasizes a form of learning that is highly deterministic, has always struck me as stodgy and no fun. Dr. Seuss is one of my favorite authors, and language ought to be playful and vibrant. I’ve yet to meet anyone who, having grown up on Dr. Seuss, is worse off for it, only able only to speak in wacky rhymes. If I did meet such a person, however, I’m sure I would be impressed.

Still, language devoid of meaning is less interesting than language replete with meaning. Knowing how to pray in Hebrew might help you feel at home in a synagogue, but knowing how to understand those prayers would help you feel at home with the liturgy itself. If we want people to learn Hebrew for non-practical reasons, it is possible that we still have to teach it to children as if their plane to Tel Aviv were leaving in a month.

This is illustrated by two different approaches to Hebrew school pedagogy I myself experienced. One was the Hebrew school I attended from first grade until just before my Bar Mitzvah. The other was a program I taught in New York for two years.

My own Hebrew school, as I mentioned, was focused on blessings and letters. Somehow we managed to fill six years studying only this. Jewish identity was made equivalent with the Jewish religion, and Hebrew was taught to us as a Jewish religious tool. In Hebrew school we learned how to be religious Jews, despite the fact that most of us were very secular. We learned how to pray and studied the rules of kashrut. We learned how to sing the Hebrew alphabet and read different blessings. Zehu. That’s all.

Ten years after I graduated from Hebrew school, I was an assistant teacher in a second-grade afterschool Hebrew program. It was run through JCP Downtown, the secular Jewish community center and preschool where I was employed. The head teacher was an Israeli woman named Iris who had lived in New York for years. In this program, our focus was on Israel, not Judaism. The children learned about Israeli food, customs, and geography. The Hebrew they were taught was modern and conversational. By the end of the year, they could have short conversations with one another in Hebrew about what they were wearing and where they were from. They learned so well, I believe, because their teacher could actually speak Hebrew, as opposed to just being able to read it or pray in it.

I’d be quick to recommend this second approach over the first. Quite simply, I think the students learned more Hebrew by being able to actually use it with one another. The practical application of a language often provides the motivation needed to learn it. I experience this in my daily life. Each time I have a successful encounter with someone in Hebrew, I feel a rush of exhilaration and the desire to study further. The fun of learning languages is being able to use them.

But the primary difference between these two different approaches is that one focuses on Hebrew as the liturgical language of Judaism while the other approaches Hebrew as the language of Israeli Jews. This, ultimately, is not a question of language but of Jewish identity. This is the dichotomy at the heart of all conversations of Jewish identity in the diaspora: Judaism vs. Israel.

The story of Hebrew’s revival in Israel is a remarkable one. Somehow, so many people from so many different places managed to adopt a shared language. Hebrew was not the language of the majority or the easiest language to learn. It was a new language to all. Yet it became the mother tongue of a nation, like the Tower of Babel in reverse. This demonstrates a language’s extraordinary power to connect people.

Ten years after I left Hebrew school, I realized that I connected with very little of the Jewish identity it taught me. I am not religious, nor do I pray in Hebrew with any regularity. Yet I still felt deeply connected to my Jewish identity. The question then becomes one of why and how? If I’m not religious, in what sense am I Jewish? How do I express my Judaism? Moving to Tel Aviv, as many Anglos living here will tell you, relieves this tension. Here, one can feel Jewish without having to do very much about it.

I am sure there will be graduates of the Israel-focused Hebrew school where I taught who will grow up and realize that they too feel deeply connected to their Jewish identity, but not in the way their Hebrew school tried to teach them. They may find themselves politically or culturally disconnected from Israel. Or they may simply feel Israel is not their country, so why speak its language? Whatever one’s personal feelings on the issue, it is a fact that many diaspora Jews feel no particular connection with Israel.

Israel and Judaism will always be relevant to Jews for myriad reasons. But they will never be important to all Jews in the same way. Perhaps they are simply not the best candidates for a centerpiece to our culture. Religion will always exclude those who don’t believe and nationalism will always exclude those who don’t belong.

The problem, if it can be called a problem at all, was articulated by Leon Wieseltier in his essay “Language, Identity and the Scandal of American Jewry.” Tackling the issue of Hebrew illiteracy among American Jews, Wieseltier points out that “We cannot teach our children what to believe; or rather, we can try to teach them what to believe, but we can never be certain of the success of our effort.” Understanding the issue this way, a Jewish identity based solely on the transmission of beliefs—translated into English, of course—will be only sporadically successful.

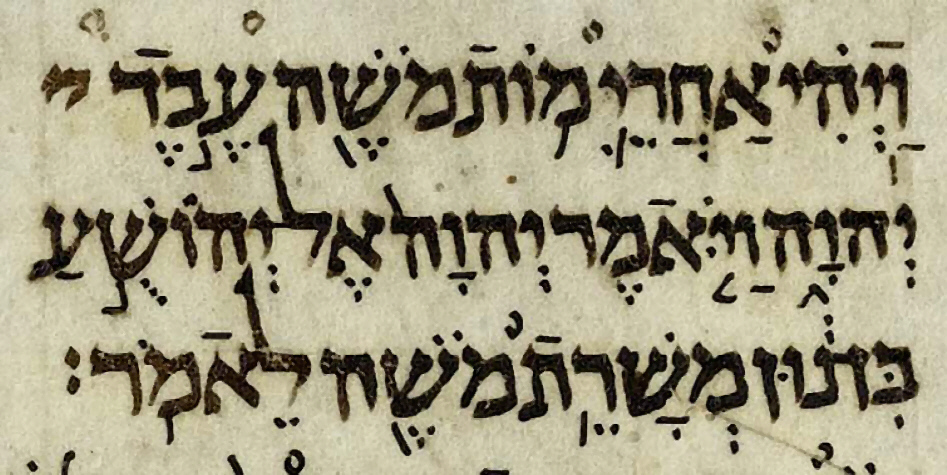

The first verses of Joshua in the Aleppo Codex, a medieval manuscript of the Hebrew Bible. Photo: Wikimedia

But for Wieseltier and, I believe, most Jewish parents as well, the “freedom of mind” of the next generation of Jews is something to be thankful for. This, of course, is more demonstrable in theory than in practice. A child’s freedom of mind will often cause a parent some concern. And what do these Jewish parents worry about, exactly?

I asked my own father to chime in on the issue. Despite having raised us in a house where Jewish identity was an un-emphasized given, he somehow ended up with one son in Israel and the other a Birthright graduate married to a nice Jewish girl from Chicago. I started by asking about the marriage. “How important to you was it that Zack married a Jewish girl?” He thought about it. “I would have been happy with anyone Zack chose,” he said. “Jew, Catholic, atheist, whatever. But I’m happy that I’ll get to go to Bar Mitzvahs and attend the Bris.”

He was relieved, I think, that the Jewishness of the family would continue, though he was not very concerned with the details of how it would do so. When parents do get hung up on the details, I would guess that the root cause is the fear that deviation from tradition will eventually break the chain of Jewish continuity.

Wieseltier touches on this anxiety, which he characterizes as an intrinsic and primal diaspora feeling. “A transplanted culture will always have a powerful anxiety about authenticity,” he writes, “about demonstrating its fidelity to, and even its subaltern relationship to, its circumstances of origin.” In other words, in the Diaspora there is always a need to demonstrate identity, whereas a non-transplanted culture can embody its identity without self-conscious demonstrations of it.

Controlling how your child demonstrates their Jewishness is as impossible as controlling their beliefs. But creating a child who feels inherently Jewish—with fewer strings attached—may be a more attainable goal for Jewish parents and educators.

From this perspective, I can think of no better future for Jewish education in the diaspora than a focus on the Hebrew language.

“If we cannot make sure that we will be followed by believing Jews, we certainly can be sure that we will be followed by competent Jews,” writes Wieseltier. “A competent Jew is not destroyed by his questions, because he can look for the answers himself.”

This competence has a double-edged nature. Looking backward, it connects a Jew to his “founding literature,” which he or she can now read in the original. Looking forward, it implies that competent Jews can do more than just transmit tradition but also contribute to it.

In the Christian New Testament, one of Jesus’ parables says that no man should put new wine into old wineskins. In contrast, scholar Gershom Scholem once wrote that the project of Jewish mystics throughout history has been to do precisely this—pouring new wine into old bottles. The use of modern Hebrew is precisely this. The old bottles are the forms and structures of ancient Hebrew. The new wine is the context and meaning these words inherit.

What young Israeli Jews have is the ability to experience their Jewish identity as second nature. This is exactly what young Jewish people in the diaspora do not have. To be Jewish in the States is to participate in a certain number of demonstrable acts. The actual number of acts, and the nature of them, is different for each individual. They range from synagogue attendance and keeping commandments on one end to Birthright trips and reading Philip Roth novels on the other.

I’ve heard Israelis say things along the lines of “I don’t need to fast on Yom Kippur. I speak Hebrew.” Similarly, young Americans in Israel enjoy getting to experience their Jewish identity outside of the Jewish structures set up by their parents. While my father’s Jewish identity is wrapped up in his yearly attendance of the Kol Nidre service, I have a different set of options as a Hebrew speaker. For example, I can listen to Shlomi Shaban’s “Motek, At Etzli B’Rosh” (a cover of Bob Dylan’s “Mama, You Been on my Mind”) while sitting with friends at our favorite bar, Har Sinai (Mount Sinai).

Hebrew is a language of great scope. It is both ancient and modern, connected to our faith and our land but dominated by neither. To arm children with fluency in Hebrew is to give them a freedom to participate in and build the culture it fosters. The philosopher Frantz Fanon said that “to speak a language is to take on a world, a culture.” A language consists of letters, words, and structures, but within this framework anything can be said.

To a great extent, this mixing of classical Jewish sources with modern culture defines how Jewish identity is expressed in a Hebrew-speaking environment like Israel. I can illustrate this with the story of my first Yom Kippur in Tel Aviv. The previous Yom Kippur, I was in New York, and for the first time I chose not to go home that day. I stayed in the city and didn’t fast. The day passed uneventfully. I completely forgot that it was Yom Kippur, as if it had nothing to do with me. There was something somber about this.

My first Yom Kippur in Tel Aviv was entirely different. I didn’t fast or go to a synagogue. I sat on my balcony as the sun went down and saw the shops close and the streets clear of cars. I heard the radio go silent, leaving only a bit of static as a reminder that the machine still worked. I saw children, in hoards, take to the streets on bicycles and I ran down to join them.

I spent most of that day on my bicycle with my roommate, Ben, who is Israeli. When the next day’s sunset arrived we returned to the balcony to watch the city grind back into motion as surely as it had halted a day before. I didn’t feel far from Yom Kippur like the year before. It felt real to me. Irrespective of what I did to commemorate it or demonstrate my fidelity to it, it was happening. But still I thought of my father on his way to the break-fast at my Uncle Bob’s house, stopping at the cemetery to place a stone on his father’s grave. I felt homesick.

“Do you know why Jews place stones on graves?” Ben asked.

I said I didn’t. I had thought about it before, but had only a handful of guesses.

“The Hebrew word for stone is Even: spelled Aleph, Bet, Nun,” Ben said. “It contains both Av and Ben, father and son.”

It is one thing to hear a word and another to understand it. It’s the same for tradition and identity. To understand is to be within. This is one of the powers of language, which is increasingly and mistakenly regarded as a tool instead of a way of being. If Jews in the States are missing something, it is precisely that. We do not lack a way of doing. Nor do we lack a way of believing. Those are available. We lack a way of being. To create a Jewish people that speaks Hebrew might fill this void, as it has for me and continues to do so as I sit down to read my Hebrew copy of Harry Potter.

![]()

Banner Photo: Nati Shohat / Flash90