For people who hold Israel to blame for the deterioration of ties with the U.S., the former ambassador’s firsthand account poses a serious challenge.

The last six years of Israeli-American relations have been characterized by both a deepening security partnership and—at the same time—acrimonious, occasionally personal, and often public disagreements on political issues.

A prevailing orthodoxy has emerged to explain this, one that creates very little dissonance for Americans whose views are basically liberal and not explicitly anti-Israel. The orthodoxy holds that the tensions between Washington and Jerusalem are the fault of an Israeli government that prioritizes settlements over peace and interferes in domestic American politics in an attempt to sabotage a diplomatic opening with Iran. The explanation for this is found in Israel’s “increasing rightward shift” and the personality of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. It is an orthodoxy championed by the likes of New Yorker editor David Remnick and assumed implicitly by The New York Times.

This orthodoxy is easy for American liberals to accept, particularly the bulk of American Jewish liberals. It also has a veneer of credibility, as Israel’s government has at times appeared to prefer policies that privilege the settlement enterprise over Israel’s more pressing security needs. At other times, its prime minister has publicly acted in ways that make him seem a bit too close to some of President Obama’s nuttier domestic opponents.

But this is not the entire story or even most of it, and the memoirs of Michael Oren, who was Israel’s ambassador to Washington during the crucial years of 2009-2013, will force a complete rethink of the orthodox narrative.

Readers of Oren’s previous historical writing, most notably Six Days of War and Power, Faith, and Fantasy, will not be surprised by his new book, Ally: My Journey Across the American-Israeli Divide. The reader encounters the same trademark historical method, with its focus on the dilemmas and information deficits of key decision-makers. Oren’s historical writing is never about defending an all-encompassing thesis or—as in much writing on Israel—drawing up an indictment. His histories are fundamentally human; but in this history, one of the humans involved is Oren himself.

And what a story it is. In a manner unsurprising to anyone who has followed the life arc of any Israeli male, Michael Oren in his mid-20s evinces a maturity far beyond his years, whether he is fighting in Lebanon or enduring a KGB interrogation while trying to reach out to Soviet Jews. At the same time, Michael Oren in his early 40s lives in a suspended adolescence, squeaking by in a tiny apartment and trying to figure out what he will do when he grows up. His tales of aliyah, career, marriage, fatherhood, and far more rushed trips to the emergency room than anyone should have to endure over a lifetime are related in an endearing, revelatory, and often poignantly self-aware manner.

It’s not the Michael Oren bildungsroman that will or should concern most readers of this book, however, but rather the deft challenge his book poses to the aforementioned orthodoxy regarding the crisis in U.S.-Israel relations that began in that long-gone winter of 2009 when Barack Obama stepped into the White House and Benjamin Netanyahu returned to the Prime Minister’s Office for his second term.

Oren dispatches the easy targets without much effort or energy. Radical Left anti-Zionists are a constant irritant, though the ambassador seems remarkably tolerant of them. Right-wing Republicans who want to use the issue of Israel as a means of attacking President Obama, even when they are doing long-term damage to Israel’s standing, are even more of a nuisance; but they also don’t merit more than a few short, explicit condemnations.

Oren’s real target is a broad, Center-Left liberal consensus; one that is largely sympathetic to President Obama and views itself as mostly pro-Israel. But Oren doesn’t explicitly attack this consensus the way he does the polemicists from Right and Left who occasionally made his job difficult. For the most part, he leaves judgments aside and presents a long narrative that ultimately paints a damning picture of an American administration that is—at times because of ideology and at other times because of incompetence—unable to process events in the Middle East. Yet it is very keen on expressing its impotent rage in well-publicized and self-defeating confrontations with its only dependable ally in the region—Israel.

This is more than just effective rhetoric; it is also quite clearly autobiographical. Oren begins the Obama era as a private citizen freezing on the Washington Mall, choked with emotion at the sight of America’s first black president being inaugurated. But then he watches the collection of mini-crises, manufactured eruptions of outrage, and tendentious and personal leaks against the Israeli prime minister that have no parallel even with America’s enemies, much less its friends. Oren reacts first with bewilderment and ultimately acceptance—a reaction that all but the most partisan readers will have as the book progresses.

Oren chronicles how the administration slights Israel over its efforts at foreign aid, indulges the provocations of the openly anti-Semitic leader of Turkey, insults Israel’s historic rights before the Arab world, and mocks Israel’s security fears with its allies in Europe. It violates a decades-old understanding between the U.S. and Israel that there will be “no surprises” between them by ironing out fastidiously diplomatic “terms of reference” that take both Israeli and Palestinian demands into account, but then announces the Palestinian position—the 1967 lines as a basis for negotiations—as U.S. policy.

In the first months of the Obama administration, the president endeavored to kick-start Arab-Israeli peacemaking by demanding three parallel gestures from Israel, the Palestinian Authority, and the pro-American Arab states. All three requests were refused, but only the Israeli “no” erupted into a full-blown public crisis—though, ironically, it was the only one that eventually turned into a “yes.”

Oren reacts first with bewilderment and ultimately acceptance—a reaction that all but the most partisan readers will have as the book progresses.

Since this early crisis became the template for all future such crises, it’s worth recalling some of the details. In his first meeting with newly-elected Prime Minister Netanyahu in 2009, newly-elected President Obama demanded a total freeze on all settlement construction. Tactically, this had the effect of denying Israel a potential concession that could have been used to advance the peace process. Even worse, it placed Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas in a position in which any future negotiations without a total settlement freeze could be read as a Palestinian concession, and thus much harder to sell to his people.

Beyond the tactical flaws however, lay a bigger problem: The blanket settlement freeze was a violation of understandings already reached between the previous Israeli government and the Bush administration. Here, I quibble slightly with Oren’s account, which follows the standard narrative in the Israeli media at the time. Oren describes the Obama demand as a violation of the Bush-Sharon letters from 2004, which spelled out American policy for a long-term vision of two states, in which the 1949 armistice lines (routinely referred to as the “1967 lines”) are explicitly ruled out as a future border.

The Bush letter, however, did not endorse or accept Israeli settlement construction in the blocs that are likely to be annexed by Israel; nor does it identify the blocs or even refer to them as such. Understandings about permissible or tolerable settlement construction were a separate, more discreet endeavor between the Bush administration and the Israeli government that was only partially successful. By failing to distinguish between understandings on construction in the near term and a firm American commitment to a political settlement in the long term, Oren is granting broad allowances to both sides.

First, he is letting Netanyahu off easy. In his zeal to protect his settler constituency, the prime minister was willing to be dragged into a public fight over an issue that was not a vital national interest. Second, Oren is letting the president off very easy for a dramatic departure in American foreign policy. The Bush letter didn’t come out of nowhere. It was an American reward for a very dramatic and painful Israeli concession—the complete withdrawal from Gaza and the dismantling of four Israeli settlements in the northern West Bank without any reciprocal Palestinian concession of any kind and with no promise or even suggestion of peace in return.

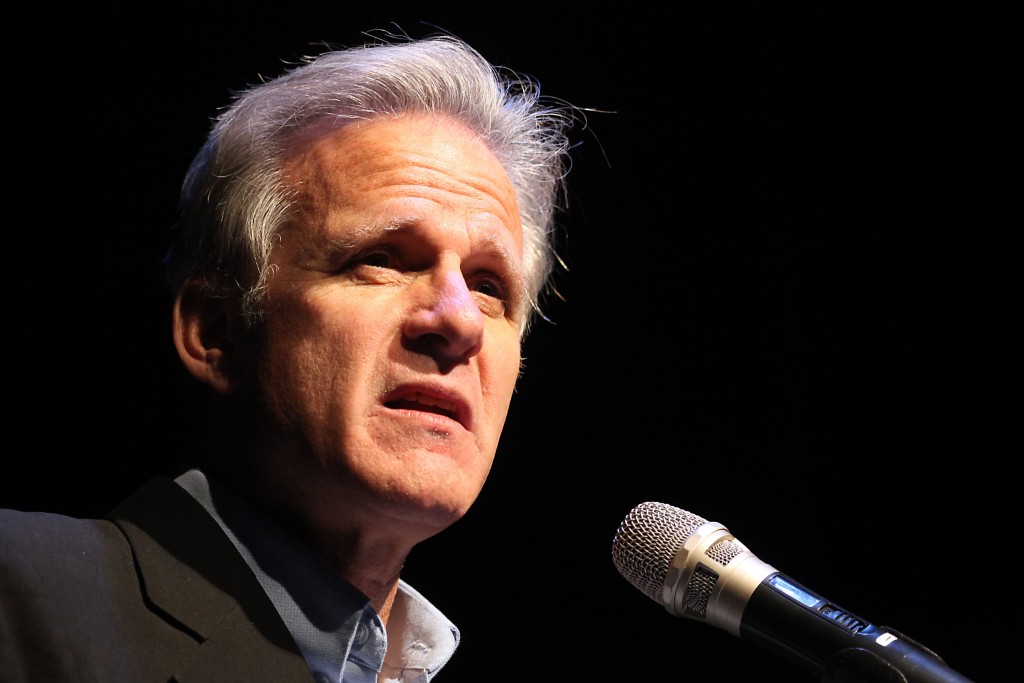

Former Israeli Ambassador to the United States Michael Oren speaks about his book Power, Faith, and Fantasy in Tel Aviv, December 16, 2013. Photo: Gideon Markowitz / Flash90

Thus, Israel in 2004 was embarking on a very risky withdrawal and getting nothing in return but an American commitment that the new administration pretended did not exist. Obama is often unfairly blamed for bungling American policy in places where he inherited a genuinely difficult situation from his predecessor. This, however, was the one situation in which this was not the case; yet it was this inheritance that he was most determined to abjure immediately upon assuming command.

The resulting dispute played out in a tone that was uniquely poisoned and personal in comparison to others, including much bigger and more principled disputes with leaders much less friendly to Obama or the United States. But it was eventually resolved, with Israel agreeing to a ten-month freeze on settlement construction and the United States sponsoring peace talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority.

Except that, for nine months, the Palestinians didn’t show up. And when they did, talks collapsed almost immediately. Oren’s play-by-play of what happens next is riveting. The administration makes Israel a far-reaching offer in exchange for a new settlement freeze, then leaks the American offer to the press as an Israeli demand, then rescinds the offer, then blames Israel for the collapse of the talks.

This was a pattern that repeated itself in the next round of negotiations. Israel’s concessions on statehood and territory were far-reaching, and its attempts to find a workable formula for mutual recognition went far beyond what the Israeli public was aware of; yet the Palestinian side was unable to agree to a meaningful peace. Nonetheless, in the aftermath of the process’ collapse, the Obama administration led a coordinated campaign to place the blame on Israel and settlement construction. It then took a back seat while American allies ganged up on Israel and the Palestinians pursued a course of unilateral action at the UN and the ICC, as well as forming a unity government with Hamas. “The Palestinians,” Oren writes about both rounds of talks, “pocketed Israeli and American concessions and then left the table.”

The story of the final collapse—the canceled prisoner release, the almost-deal to revive talks, the ceremonious Palestinian signing of treaties in violation of their commitments, the reconciliation with Hamas, Kerry’s poof moment, and Martin Indyk’s barely anonymous interview pinning all the blame on Bibi—is well known.

Oren, of course, was no longer ambassador by the time the 2013-2014 talks fell apart last April, having left his post six months earlier. He was still ambassador, however, when the negotiations began and Israel agreed to the conditions governing them in July 2013. The administration’s playbook this time around was nearly identical to the previous round: Squeeze concessions from Israel before negotiations begin, allow the Palestinians to pocket more concessions during the negotiations as a baseline for unilateral action, watch as the Palestinians refuse any agreement that involves actual reconciliation with the presence and legitimacy of a Jewish state, condemn Israel when the talks fail, and sit back as Europeans and others seek to make Israel “pay” for its “intransigence,” all while pursuing a parallel diplomatic initiative with Iran that an isolated Israel was powerless to block.

Yet Oren’s book leaves the reader wondering what his assessment of all this was. Oren refers constantly to his role as both an explainer of Israel to the Americans and an explainer of America to the Israelis. But reading his memoir, it remains unclear if he understood in real time what the administration’s strategy was and if he succeeded in “explaining” it to his government back home. For example, by agreement with the U.S. and the Palestinian Authority, Israel was to agree to one out of three suggested preconditions: A new settlement freeze that would include East Jerusalem, a broad release of convicted Palestinian terrorists, or an a priori Israeli acceptance of the 1967 lines as the basis for negotiations. Between the lines, it is clear that Oren believed the best option was the settlement freeze, but it’s not clear how strongly he urged it on the prime minister or if he understood that either of the other two options was a trap.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu shakes hands with Israeli Ambassador to the United States Michael Oren as Netanyahu arrives in Washington, D.C., March 5, 2012. Photo: Amos Ben Gershom / Flash90

The trap should have been obvious enough: A Palestinian agreement—on any borders and in any international framework—that would recognize a Jewish state and declare an end to the conflict was never possible to reach in nine months. Even if it were possible, it could never have been implemented by a Palestinian government that barely controlled the West Bank and didn’t control the Gaza Strip. Any concession Israel made would simply become the baseline for either future negotiations or an internationally-imposed settlement that would not include Palestinian acceptance of Israel’s presence and legitimacy. More importantly, anyone who had lived through the previous round of talks should have known, must have known, that the administration would blame Israel for the failure and would use settlement construction as an excuse. Netanyahu might have thought he was picking only one precondition out of three, but the settlement precondition was always going to be used against him. I couldn’t glean from Oren’s book whether anyone on the Israeli side took this into consideration, much less thought about what to do when negotiations inevitably failed.

For Michael Oren, this is a particularly glaring lacuna, since once out of office, he more than any other public figure in Israel has made a lonely cause of planning affirmative Israeli action in the absence of diplomatic progress. Oren has done so much over the years to get an uninterested Israeli public to wake up to the importance of having a “Plan B” that it’s thanks to him that the Hebrew language now has a term for it (it’s plahn-BI, said even by Oren himself with a strong sabra accent). Yet it’s not clear from reading his memoirs if he or anyone else doubted that the second round of negotiations would lead to an actual agreement. This is a bit shocking given Abbas’ well-known positions, to say nothing of the chaos that gripped the Arab world in 2013 and the easily ignored fact that the Abbas regime was ruling only half of the Palestinian territories at the time. If there were pessimists on the Israeli team, did any of them formulate a Plan B?

Oren doesn’t say. Instead, he describes how shocked the Israeli team is by the way the American administration lets Israel take all the blame for the talks’ failure, then lies low while Israel’s enemies take action in international forums and America’s friends formulate punitive measures. The administration’s behavior in May-June 2014 was certainly shocking, but it should not have been surprising, least of all to Oren himself.

There is no room for surprise anymore as this administration moves forward with its opening to Iran and its risky gamble on the Iranian nuclear program. Pro-Obama, pro-Israel liberals have lived in a dissonance-free zone as long as they embraced the prevailing orthodoxy of Netanyahu’s malfeasance. Oren’s book does not in any way exonerate Netanyahu from responsibility for allowing the settlement issue to limit Israel’s policy options or from misunderstanding a changing American domestic political landscape. But no serious reader from the camp that Oren is trying to address can close this book and still be free of that dissonance.

If that dissonance sparks a more robust and honest conversation about U.S.-Israel relations, and in particular about the problems of the last six years, this book will have made an enormous contribution. If it is mistakenly received as an anti-Obama Right-wing screed, embraced by the President’s conservative foes and caricatured and dismissed by everyone else, we will all be poorer for it.

![]()

Banner Photo: Miriam Alster / Flash90