In Lebanon, Iraq, Yemen, and elsewhere, Tehran has perfected the art of gradually conquering a country without replacing its flag.

The Middle East is witnessing the birth of a new Persian empire, under the aegis of the Islamic Republic of Iran. In fact, when Iranian officials gloat over their control of four Arab capitals, they are being uncharacteristically modest. Tehran’s hegemony has spread far beyond Baghdad, Beirut, Damascus, and Sana’a. But this latest incarnation of Imperial Iran is unique in that it is virtually invisible. Iranian flags do not fly above the centers of government in these capitals, and the foot soldiers of the elite Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps – Quds Force (IRGC-QF) do not march in their streets. Tehran has contracted this clandestine conquest out to an ever-expanding list of loyal proxies. They mutate and fracture into new entities, adopt new names, and operate in different roles and locations; but this constellation of proxies orbits around Iran, effectively masking the Islamic Republic’s increasing control over the Middle East.

Tehran coordinates and provides a wide array of support and aid to its proxies, mainly through the IRGC-QF and its commander, Qassem Suleimani. It seems important, then, to recall that the U.S. Treasury Department has designated the IRGC-QF and its commander for activities related to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and support for terrorism, accusing the Quds Force in 2007 of providing material support to the Taliban and other terrorist groups. The Justice Department cited the group as “conduct[ing] sensitive covert operations abroad, including terrorist attacks, assassinations and kidnappings, and is believed to sponsor attacks against Coalition Forces in Iraq.”

A painting of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini on the walls outside the former American embassy in Tehran. Photo: David Holt / flickr

To understand the nature and danger of Iran’s ever-multiplying proxies, one must understand their ideology: Most are Shi’a Islamists who adhere to the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s extremist concept of “Absolute Wilayat al-Faqih” (Guardianship of the Jurist), which maintains that all issues, including the governance of a country, must be in the hands of the Jurisprudent Ruler, who is the vicar of the Awaited Mahdi. In many ways at odds with traditional Shi’a jurisprudence—which emphasized political quietism—Khomeini’s innovated ideology declared Islamic jurists to be the only true source of religious and political authority. Their pronouncements must be obeyed “as an expression of obedience to God,” and their rule takes “precedence over all secondary ordinances [of Islam] such as prayer, fasting, and pilgrimage.”

As the spiritual father of the Islamic Republic, Khomeini was the first to hold the post of Rahbar (Supreme Leader), and since his death in 1989, his worldview and political thought made their way into Iran’s post-Revolutionary constitution, and have continued to hold sway over the Islamic Republic’s domestic and foreign policies. Indeed, politicians like Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s current Rahbar, strive to adhere to his teachings as much as possible in their decision-making.

Hatred of the West and combating its various founding ideologies—capitalism, secularism, communism, and Zionism—was integral to Khomeini’s ideology, who considered “export[ing] our Revolution to the whole world” one of “the great goals of the revolution,” for the purpose of “establishing the Islamic state world-wide.” And until such time when the world submitted Iran’s Revolutionary twist on Islam, “there will be struggle.”

Khomeini singled out the United States for special opprobrium. This was a theme he constantly preached over the course of his religious and political career, expressing his hope and confidence that, “The Iranian people…will keep alive in their hearts anger and hatred for…the warmongering United States. This must be until the banner of Islam flies over every house in the world.” America received this place of dubious honor in Khomeini’s worldview because he considered it the “foremost enemy of Islam” and “a terrorist state by nature that has set fire to everything everywhere….Oppression of Muslim nations is the work of the United States.”

Tehran’s conquest of the Middle East has been contracted out to an ever-expanding list of proxy groups.

Ayatollah Khamenei has not abandoned his predecessor’s ideological path, and over the past three decades—first as president and then as Supreme Leader—he has expressed his contempt for the U.S. with remarkable consistency. Many, though not all, of his closest confidantes have claimed that this is an outgrowth of his adherence to Khomeini’s belief that the Islamic Republic and the United States can only have a relationship akin to that between “a wolf and a sheep,” with Khamenei emphasizing that “the conflict and confrontation between the two is something natural and unavoidable.” This, he believes, is because Washington is intrinsically hostile to Iran due to “the Islamic identity of our system.” Any other issue on which America expresses opposition to Iran—Iran’s nuclear ambitions, hostility toward Israel, and support for Hezbollah—are simply excuses for America to further its anti-Islamic goals.

Therefore, he thinks Iran “needs enmity with the United States” in order to prevent America’s supposedly corrupting influence and lax morals from seeping into the country and weakening the Islamic Revolution. In fact, he rarely misses an opportunity to express the Iranian regime’s unyielding opposition to “Global Arrogance,” his favorite term for the United States, only slightly less damning of a title than Khomeini’s “Great Satan” label. And so, at a time when Khamenei was willing to entertain former president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani’s efforts to improve Iran’s relations with its Arab neighbors and European countries, he was rigidly opposed to any such rapprochement with the United States, an intransigence based on Khamenei’s belief that combating America’s influence, specifically, was one of the primary goals of the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

This overt hostility is not confined to the current Supreme Leader and his predecessor—who hold absolute authority over any government—but has become ubiquitous among Iranian government officials. Even a touted “moderate” like President Hassan Rouhani—who would not have his post unless he were completely loyal to the Islamic Revolution’s ideals—has said, “Saying ‘death to America’ is easy. We need to express ‘death to America’ with action.” These views have been echoed repeatedly by members of Rouhani’s cabinet.

In short, Iran’s anti-Western animosity and enmity—particularly focused against the United States and Israel—is a critical component of the Islamic Republic’s political culture and policies. Its Shi’a proxies, which by and large have sworn fealty to the Iranian Supreme Leader, echo the views of the man whose words they view as, in essence, the vicarious and infallible word of God.

Iran’s Revolution led to an “awakening” of Shi’a Muslims worldwide, hijacking the traditionally politically quietist religious sect and injecting a militancy into its theology, imbuing it with temporal demands. As such, Iran has spawned numerous Shi’a proxies across the Arab and Muslim world.

Perhaps the most striking example of this turn from quietism is Yemen’s Ansarullah, better known as the Houthis, currently the country’s de facto rulers. The Houthis differ from most of Iran’s other Shi’a proxies in the nuances of their theological history. Yet they are now acting at the behest of Iran – causing panic in neighboring Saudi Arabia – and their banner carries the same “Death to America” and “Death to Israel” slogans regularly chanted by the Tehran regime’s loyalists in Iran, Lebanon, and Iraq. Despite their shared enmity with the United States towards Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), the Houthis held an uncompromising opposition to the government’s alliance with the United States.

Though there is no public evidence of the Houthis espousing adherence to Absolute Wilayat al-Faqih, the group’s founder, Hussein Badreddin al-Houthi, spent considerable time in Iran. There he was influenced by the Khomeinist theology, believing that the Iranian model could be applied in Yemen as well. Iranian officials have confirmed these ties, which includes financial and military support for the Houthis, with a senior Iranian official saying that the Quds Force even placed “a few hundred” members in Yemen to train the Houthis. When the Houthis overran Sana’a, Iranian officials boasted that Yemen’s capital was now in Iran’s possession.

But while the Houthis have made the most recent noise, Iran has been using proxies to dominate other countries since the 1980s. Lebanese militia-cum-political party Hezbollah remains the most successful and most prominent Iranian revolutionary export. Indeed, Gilbert Achcar of the University of London has called it “the most prestigious member of the regional family of Khomeinism.” The Lebanon-based terrorist group is cut from the same ideological cloth as the Islamic Republic, which, according to former CIA intelligence analyst Kenneth Pollack, is Hezbollah’s model and inspiration. Eitan Azani, the deputy executive director of the Institute for Counter-Terrorism at IDC Herzliya, has said that Khomeini and his successors serve as Hezbollah’s ultimate source of religious, political, and ideological guidance and authority. Hezbollah fully accepts the concept of Absolute Wilayat al-Faqih, and openly acknowledges Khomeini as its faqih, leading Augustus Richard Norton of Boston University to call Khomeini Hezbollah’s “undisputed, authoritative leader.”

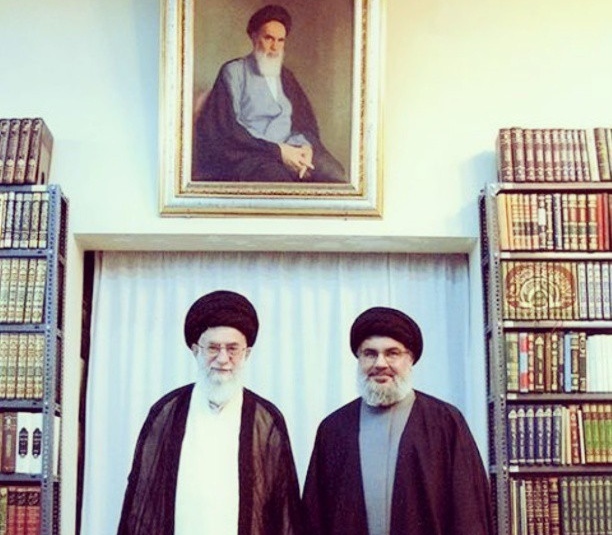

Hezbollah itself acknowledged this fact in their 1985 Open Letter, stating, “We obey the orders of one leader, wise and just, that of our tutor and faqih, who fulfills all of the necessary conditions: Ruhollah Musawi Khomeini.” With the death of Khomeini, Hezbollah did not end its submission to Iranian authority, but reaffirmed its allegiance to the current Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei. Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah himself declared in May of 2008 that he was “proud of being a member of the Wilayat al-Faqih party.”

An undated photo of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei meeting with Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah. Photo: Iftikh / flickr

Hezbollah’s connection to Iran is not limited to professions of ideological fealty. In his book Deadly Connections, Daniel Byman, Research Director of the Brookings Institution’s Center for Middle East Policy, notes that Hezbollah does not only accept the concept of Absolute Wilayat al-Faqih in a general sense, but also subscribes to Iran’s particular worldview and its enmity toward the United States and Israel. Hezbollah’s implementation of its Islamist strategy is closely linked to Iran’s policy of exporting the Islamic Revolution abroad while consolidating and expanding it at home. In effect, this makes Hezbollah an arm of Iranian foreign policy. Indeed, Hezbollah has repeatedly fought wars that, in effect, solely benefited Iran. Whether combatting Israel, participating in the Syrian civil war, or sending its militants to Iraq, Hezbollah is at the service of its masters, often at the expense of its own, or Lebanon’s, interests.

Hezbollah is unquestionably the most prominent Iranian proxy on the international scene, having carried out a series of attacks abroad through what Matthew Levitt, Director of the Stein Program on Counterterrorism at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, has called “Hezbollah’s international terrorist wing.” Known alternatively as the Islamic Jihad Organization or External Services Organization, it has received strong support from the IRGC and Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence. But perhaps the most telling example of the close relationship between Iran and Hezbollah is that Hezbollah has also operated within Iran itself, reportedly helping the regime to crush internal dissent. Indeed, Hezbollah sent approximately 5,000 of its fighters to participate in the suppression of the “Green Revolution” in 2009.

But while Hezbollah has been the most famous Iranian proxy, Tehran has also established a number of loyal militias in neighboring Iraq—to the point where (with the exception of the autonomous Kurdish region in the north) the entire country’s security infrastructure has come under the sway or even direct control of Tehran. The Badr Organization, which, like Hezbollah, has molded itself into a political party while retaining its military capabilities, is probably the most prominent. Indeed, it is particularly telling that the logo of Badr’s military wing is almost identical to that of the IRGC, Hezbollah, and other Iranian terrorist franchises.

The Badr Organization was formed in November of 1982—shortly after the Iran-Iraq War broke out—as the Badr Brigades, the military wing of an Iran-based Shi’a Islamist party called the Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI). Badr was comprised of defectors from the Iraqi army who fled to Iran and joined SCIRI, and were originally recruited, trained, and equipped by the IRGC. Badr fought on the side of Iran during the war, and its current leader, the unabashedly pro-Iranian Hadi al-Amiri, was among its ranks. After the war ended, Badr participated in the uprisings against Saddam Hussein in the early 1990s, during which, according to al-Amiri, the group received Iranian support just as “Iran supports Iraq now.”

Al-Amiri, now Iraq’s Transportation Minister, makes no secret of his loyalty to Iran, and has openly stated, “I believe in the principle of Wilayat al-Faqih, the Absolute Wilayat al-Faqih, as it currently exists in Iran.” He has been photographed with Quds Force commander Qassem Suleimani on multiple occasions, and has called Suleimani his “dearest friend.”

Another prominent Iranian proxy is Kata’ib Hezbollah (KHA). Established in 2003, it is an offshoot of the “Special Groups”—Iranian-backed elements of radical Iraqi cleric Muqtada al-Sadr’s Mahdi Army—though it is now an entirely separate entity. It is a designated foreign terrorist organization, and receives funding and training, as well as logistic and military support, from IRGC-QF and Hezbollah. Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, an adviser to the IRGC-QF’s commander Qassem Suleimani, is known to be one of the group’s senior leaders, and has been designated by the Treasury Department as posing a “threat to the stability of Iraq,” which said that al-Muhandis and KHA “have committed, directed, supported, or posed a significant risk of committing acts of violence against Coalition and Iraqi Security Forces.” Michael Knights, Lafer Fellow at the Washington Institute, has noted that KHA is “firmly under IRGC-Quds Force control.” Like the aforementioned groups, KHA espouses the Khomeinist ideology of Absolute Wilayat al-Faqih.

Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (AAH), established sometime in July of 2006, is another Iranian-controlled proxy in Iraq that operates under the patronage of Qassem Suleimani. It considers Ayatollah Kazem al-Haeri, a Khomeinist scholar of Iraqi origin residing in the Iranian holy city of Qom, to be its spiritual leader. On his personal website, Ayatollah Haeri states in a fatwa, “I believe in the Absolute Wilayat al-Faqih.” AAH has also boasted about launching a 2012 poster campaign promoting Ayatollah Khamenei throughout Iraq. Under Iranian orders, this group is now fighting in Syria on behalf of Bashar al-Assad’s Iranian-backed regime.

It is not alone. Liwa Abu Fadl al-Abbas (LAFA) is perhaps the most important Iranian proxy in Syria. It first made its appearance in the fall of 2012 and, as Phillip Smyth of the University of Maryland has noted, fights in Syria under the pretense of defending the Sayideh Zainab Shrine and surrounding Shi’a neighborhoods in southern Damascus. It is made up of a small number of native Syrian Shi’a, but the majority of its members are foreign Shi’a fighters. Smyth further noted that these fighters are mostly drawn from Iranian-backed organizations like the aforementioned Kata’ib Hezbollah and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. LAFA also openly identifies with Lebanese Hezbollah. The original parties to which LAFA’s foreign fighters belonged were themselves ideologically loyal to Iran and its Absolute Wilayat al-Faqih ideology, indicating both direct Iranian involvement in LAFA’s creation and its ideological fealty to Iran.

Through these proxies, Iran has managed to gain direct control over certain areas of Iraq. According to Sadeq al-Husseini, the head of the Diyala provincial council’s security committee, former Iraqi prime minister Nuri al-Maliki placed Diyala under the control of Hadi al-Amiri and his Badr Organization after the virtual disintegration of Iraq’s army. Reportedly, Iran soon dispatched 500 IRGC members to Diyala in order to fight alongside Badr, though Iran’s Foreign Ministry has denied this.

A few months later, however, Iran allegedly played a major role in retaking the city of Jurf al-Sakher in Diyala’s neighboring Babil province from ISIS. Pictures circulated online showing Suleimani at the site, along with Shi’a militia fighters and al-Amiri. A local police officer, who spoke anonymously to reporters, said Iranian fighters were present on the battlefield, and a Washington Post reporter heard Farsi being spoken at a military base. Sheikh Qassem Sudani, a commander with Kata’ib Hezbollah—another Iranian-backed militia fighting in the area—partially admitted to the Iranian presence.

The presence in and, in some areas, domination over parts of Iraq by these groups should not be viewed as a local or even regional issue. Their worldview and ambitions are international. Indeed, their animosity toward the West, its allies, and Israel is not only ideological, but has manifested itself in some of the deadliest terrorist attacks committed against Western targets in recent times, almost all at Iran’s behest and mostly carried out by Hezbollah. A list of the attacks committed by Iran and Hezbollah is too long to be detailed here in its entirety, but a few of the major incidents deserve mention.

On November 11, 1982, a Hezbollah suicide bomber drove a car filled with explosives into an IDF headquarters in Tyre—from which the IDF was running its Lebanon War operations—killing 75 soldiers. On April 18, 1983, an explosive-laden van rammed into the U.S. embassy in Beirut, killing 63 people, including 17 Americans, among whom was the CIA’s chief Middle East analyst, Robert C. Ames. After the attack, a pro-Iranian group calling itself the Islamic Jihad Organization—a cover name for Hezbollah’s terrorist wing—claimed responsibility, saying that the attack was “part of the Iranian Revolution’s campaign against imperialist targets throughout the world.” On October 23, 1983, the Islamic Jihad Organization carried out simultaneous attacks against the U.S. Marine and French army barracks in Beirut—both forces had been sent to Lebanon as peacekeepers—killing 241 Americans and 54 French. Hezbollah recently boasted about its responsibility for the attack in a nasheed it produced to commemorate the slain Jihad Mughniyeh, son of Hezbollah’s terrorist mastermind Imad Mughniyeh. The song included the lyrics, “I am Jihad, son of the hero, who led columns of the defiant; the one who felled elite soldiers, marines, and well-armed armies.”

Iran’s animosity toward the West is not only ideological, but has manifested itself in some of the deadliest terrorist attacks committed against Western targets in recent times.

On November 4, 1983, Hezbollah carried out another attack against the Israeli headquarters in Tyre, resulting in the death of 28 Israeli soldiers. On December 12, 1983, Iran tasked 17 members of the Iraqi Shi’a Da’wa party—supported by the Islamic Jihad Organization—with carrying out attacks against targets in Kuwait. These attacks, notes Levitt, were “in explicit service of Iran, rather than in the group’s immediate interest.” Within two hours, they carried out a series of six coordinated bombings against the American and French embassies, the Kuwaiti airport, the Raytheon Corporation’s headquarters, a Kuwait National Petroleum Company oil-rig, and a government-owned power station. The shoddy assembly of the explosives ensured that the death toll was relatively low, with five people killed. On September 20, 1984, Hezbollah’s Islamic Jihad Organization bombed the newly re-opened U.S. embassy in East Beirut—the second such attack in less than a year—killing 23 people, two of whom were Americans. After the attack, the CIA stated that “an overwhelming body of circumstantial evidence points to the Hizb Allah, operating with Iranian support under the cover name of Islamic Jihad.” Through satellite reconnaissance, U.S. intelligence discovered that a mock-up of the target had been created at the IRGC-run Sheikh Abdullah barracks in Baalbek, Lebanon in order to train for the attack.

On December 3, 1984, four Hezbollah members—including Mughniyeh—hijacked Kuwait Airways Flight 221, diverting it to Tehran. Two USAID employees, Charles Hegna and William Stanford, were killed before Iranian security forces seized control of the plane and arrested the Hezbollah operatives. Levitt notes that the “rescue was apparently a farce, engineered by Iran to give the hijackers a way out.” The BBC noted that American and Kuwaiti authorities “suspected that the hijackers were acting in league with leading members of the Iranian regime,” possibly based on passenger testimony that the hijackers received additional weapons once they landed in Tehran. The suspicions were reinforced by Iran’s refusal to extradite the hijackers and helping them go into hiding, and later confirmed by subsequent developments in Iran’s relationship with Mughniyeh, as he reported directly to Iran, was dispatched to Lebanon by Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence to supervise the reorganization of Hezbollah’s Palestinian Affairs security apparatus, and worked as a liaison between Hezbollah and Iranian intelligence.

On June 14, 1985, Islamic Jihad Organization/Hezbollah terrorists hijacked TWA flight 847 after it took off from Athens, Greece, killing United States Navy diver Robert Stethem and throwing his body on to the tarmac. As a result, Mughniyeh was indicted by the United States, along with alleged collaborator Hassan Izz al-Din, a prominent Lebanese member of Hezbollah, for the hijacking and murder. In 1985 and 1986, the group was also directed to carry out several attacks in France—coordinated by Wahid Gordji, an Iranian intelligence official—due to French support for Iraq. “In essence, Hezbollah acted as part of Iran’s intelligence and security forces,” Byman wrote.

On April 5, 1988, Hezbollah operatives, including Izz al-Din, hijacked Kuwait Airways flight 422, forcing it to initially land in Mashhad, Iran, in order to free 17 Shi’a Muslims held in Kuwait for their role in the 1983 bombings. Two Kuwaiti passengers, Abdullah Khalidi and Khalid Ayoub Bandar, were shot dead in Larnaca, Cyprus (the plane’s next stop) by the hijackers and dumped on the tarmac, before the hijackers finally surrendered to Algerian authorities at their final destination in Algiers.

The next attacks occurred in 1992 and 1994 in Argentina. They targeted the Israeli embassy, killing 29, four of whom were Israelis; and the AMIA Jewish community center, killing 85. Both attacks were assisted by Iran’s embassy in Buenos Aires, and Iran and Hezbollah’s joint responsibility was confirmed by the CIA, Mossad, and Argentina’s SIDE.

Then came the attack on the Khobar Towers in Saudi Arabia, killing 19 American airmen. An official U.S. statement said that Hezbollah al-Hejaz—a Saudi-based proxy—was responsible, and in 2006, a U.S. court found Iran and Hezbollah guilty of orchestrating the attack. Ahmed Ibrahim al-Mughassil, the head of the group’s military operations, and Abdelkarim Hussein Mohammed al-Nasser, another of the group’s leaders—both indicted by the United States—are now living in Iran. Hezbollah al-Hejaz was a Saudi Shi’a cleric-based group that formed in 1987, aligning itself with Iran and modeling itself on Lebanese Hezbollah. Backed by Iran, it operated in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Bahrain, and followed the marja’iyya (authority) of Ayatollah Khomeini, and later Khamenei, completely embracing the principle of Absolute Wilayat al-Faqih. Its long-term political goal was the establishment of an Iranian-modeled Islamic Republic in the Arabian Peninsula. The group was thought to have been entirely dismantled by the Saudi crackdown that followed the Khobar bombings, but it has reemerged after Saudi Shi’a pilgrims were attacked by religious police in 2009.

On October 11, 2011, the United States uncovered an Iranian plot to assassinate the Saudi Arabian ambassador, Adel al-Jubeir, and bomb the Israeli and Saudi embassies in Washington, DC. The planners were Gholam Shakuri, a commander in the IRGC-QF, and Manssor Arbasiar, a dual U.S.-Iranian citizen.

Finally, on July 18, 2012, a suicide bomber in Burgas, Bulgaria committed a terrorist attack against a passenger bus carrying 42 Israeli tourists, mainly young people. The explosion killed five Israelis and the Bulgarian bus driver. In February of 2013, Tsvetan Tsvetanov, Bulgaria’s interior minister, said that there was “well-grounded” evidence that Hezbollah was behind the attacks, and Europol noted that forensic evidence and intelligence information pointed to Hezbollah and Iran.

It should be noted that Hezbollah has no qualms about targeting or killing Israeli civilians, as stated by Hezbollah apologist and supporter Amal Sa’ad-Ghorayeb in her rather frank 2002 book Hizbu’llah: Politics & Religion. Sa’ad-Ghorayeb noted that Hezbollah sees all of Israeli society as an anti-Islamic, racist Zionist monolith, with Israeli civilians viewed as “hostile, militant Zionists” who are an extension of the Israeli army. Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah has said, “In occupied Palestine there is no difference between a soldier and a civilian, for they are all invaders, occupiers, and usurpers of the land.”

Disturbingly, even Israeli children are not considered an exception, as Hezbollah also views them as “occupiers.” Muhammad Raad, a party ideologue, member of its executive committee, and elected by the Iranian legislature as Lebanon’s only representative in the IRGC, stated, “We know the emotions and sympathy associated with the [killing of Israeli] children differ from those associated with adults. But in the end, they are all serving one project….One day this child will become prime minister.”

Iran’s Shi’a proxies have also wrought havoc against American and Western targets in Iraq. In fact, the attacks by Iran’s Shi’a proxies became so pronounced—one statistic states that they caused two-thirds of American casualties in Iraq in July 2007—that General David Petraeus established a special division of the anti-terrorist Joint Special Operations Command specifically tasked with “countering Iranian influence.” It did so mainly by targeting Shi’a militias, but also by pursuing the IRGC-QF operatives arming and supervising their attacks on U.S. troops.

KHA and AAH have carried out numerous attacks against U.S. personnel in Iraq, subsequently boasting about them in propaganda videos. AAH has claimed responsibility for over 6,000 attacks in Iraq, including the October 10, 2006 attack on Camp Falcon, the assassination of the American military commander in Najaf, the downing of a British helicopter on May 6, 2006, and the October 3, 2007 attack on the Polish ambassador. The most famous incident occurred in January 20, 2007, when they attacked the U.S. Army’s Karbala province headquarters, killing one soldier and abducting four more who were later killed also.

The Badr Organization has played a role in attacking American personnel as well. Prior to 2003, Badr served as Iran’s most important proxy inside Iran, and was considered an official component of the IRGC-QF, receiving weapons and training from the IRGC-QF and Lebanese Hezbollah. During the U.S. occupation, many of Badr’s senior individuals played important roles in funneling weapons to associated militant groups fighting the U.S. and coalition forces. While it attempted to hide its role in attacks against Americans, Smyth notes that, in spring 2014, “the Badr Organization … announce[d] on its al-Ghadeer TV network and official social media that it had attacked U.S. forces in Iraq.” It did so “as propaganda to recruit fighters in Syria.”

Yet this hostility toward America’s presence in the Middle East is not only directed against the U.S. presence in Iraq. In a twist that would be ironic in any other region besides the Middle East, recent reports have indicated that Iran is once again turning to al-Qaeda as a proxy, using Hezbollah to coordinate with al-Qaeda offshoot Jabhat al-Nusrah in order to attack U.S. interests in the region.

The U.S. is not the only target of these groups. They have also committed atrocities against local Sunnis in Iraq and elsewhere, exacerbating the country’s sectarian tensions and damaging the United States’ stated policy of furthering sectarian reconciliation.

This violence is nothing new, and has been known to U.S. officials for some time. During the U.S. occupation of Iraq, a 2009 U.S. embassy cable indicated that the Badr Organization had infiltrated the Iraqi security forces and was carrying out a widespread campaign of terror and murder against Sunnis. Hadi al-Amiri may have been personally responsible for ordering the killing of up to 2,000 Sunnis. One of his “preferred methods of killing” was “using a power drill to pierce the skulls of his adversaries,” a method used by lower-ranking Badr militiamen as well.

The sectarian violence did not end with the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq in 2011 or the election of Iranian-endorsed Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi on a platform of reconciliation with Iraq’s Sunnis. Though it was al-Maliki who put Diyala under the command of al-Amiri and his militia forces, al-Abadi—who holds strong pro-Iranian sympathies—has allowed al-Amiri’s divisive influence to grow, resulting in serious human rights violations. For example, Iraqi government and Western intelligence sources claim that Shi’a militias, including Badr, tortured and executed a number of what it claimed were ISIS fighters. After pushing the Sunni terrorists out of Jurf al-Sakher, Badr Organization militiamen decided to exact revenge on captured ISIS fighters and dragged their bodies through the streets. One need not sympathize with ISIS fighters to see that these actions demonstrate the similarity between the Sunni terror group and Iran’s Shi’a proxies.

These horrific actions have also extended to civilians, with the Badr Organization and others killing Sunni residents it accused of being sympathetic to ISIS. Reports surfaced in January that Shi’a militiamen arrived in the town of Barwanah in 10 Humvees, took Sunni residents—some up to age 70—from their homes, led them in small groups to a field, made them kneel, and then shot them one by one. At least 72 Iraqi Sunnis were killed by what witnesses called a collection of Shi’a militiamen and security forces, identified by their black-and-brown uniforms and green headbands emblazoned with the slogan, “Ya Hussein!” The militias and associated security forces subsequently encircled the village, preventing anyone from leaving. One of the residents, Abu Ahmed, said that the town was “surrounded for days. We have no food. We have nothing.”

These are only a handful of examples of the countless incidents of horrific violence perpetrated by Iran-sponsored Shi’a militias. Human Rights Watch has issued a series of reports chronicling these systematic abuses against Iraq’s Sunnis, which rival ISIS in their barbarism and cruelty. Though al-Amiri tried to blame these abuses on the lack of discipline among new recruits, Erin Evers—a researcher with Human Rights Watch—was unconvinced due to the Badr Organization’s “bloody history.” Evers has accused Badr of “systematic” abuses that “range from the Badr Brigade kidnapping and summarily executing people, to expelling Sunnis from their homes, then looting and burning them, in some cases razing entire villages.”

With their ideological allegiance to Iran and the concept of Absolute Wilayat al-Faqih; their ideologically motivated hostility to the United States, the West, and its allies; and their list of human rights atrocities and terrorist acts over the course of the last three decades, one would assume that these groups would be sidelined and marginalized, if not placed in the same category as ISIS.

Yet, the opposite seems to be true. General Martin Dempsey, the former supreme commander of U.S. forces in Iraq, has said that the expansion of “Iranian influence will be a net positive.” Making matters worse, President Obama’s desired Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) against ISIS and its accompanying explanatory letter propose using American forces in a support role for “our partners on the ground” and “local forces.” Any astute observer of the Iraqi and Syrian battlefield can readily see that Iran’s Shi’a militia proxies are the only groups fitting those descriptions that are leading the fight against ISIS. In effect, with the best of intentions, the AUMF is calling for the inadvertent support of some of the United States’ staunchest enemies.

Despite the old adage “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” such a policy can only backfire. Every inch of territory acquired by these groups has not been liberated from ISIS occupation, but conquered by Iran, which is a far more formidable enemy. Such a strategy is counterproductive, and supporting groups committing unspeakable atrocities against Sunnis is not a viable alternative to fighting ISIS. It will only add fuel to the sectarian fires already raging in Iraq and elsewhere, severely hindering U.S. foreign policy goals in the region. The same applies in Yemen, where the United States turned its back on its ally, President Abed Rabbo Mansour al-Hadi, and after signaling its openness to working with the Houthis, actually formed indirect ties with them, according to the White House and the group’s commanders. Houthi commanders said the U.S. has indirectly provided them with intelligence and logistical support against AQAP. This happened despite the group’s allegiance to Tehran, opposition by Saudi Arabia and the fact that the group stands poised to ignite heretofore minimal to non-existent Sunni-Shi’a tensions in the country. April Longley Alley, senior Arabian Peninsula analyst for the International Crisis Group, notes that the “most worrisome” part of the rise of the Houthis is that “by taking the lead in the fight against al-Qa‘ida, the Houthis are opening the door to a sectarian conflict that the country has never experienced.” These fires will spread, fueling recruitment by extremist groups of all stripes, and consuming the lives of countless innocents.

Most importantly, supporting Iran’s proxies aids in the expansion of Iran’s influence throughout the region, furthering Tehran’s imperialist ambitions. Iran wishes to be the hegemonic power in the Middle East, and is consciously using its many proxies to further this ambition. Ultimately, supporting Iran’s proxies could well lead to the emergence of a new Persian empire that would place much of the Middle East under the influence of a fervently anti-Western and anti-American theocracy that is, ultimately, a far greater threat than even its most brutal enemies.

![]()

Banner Photo: Neil Hester / flickr