Israel and Japan are growing closer than ever, tied together by a shared desire for trade and their mutual commitment to an international system that is currently under attack.

With the Paris terror attacks, the high-profile killing of senior Hezbollah leaders in Syria, and ISIS’s release of a hostage video featuring two kidnapped Japanese nationals monopolizing much of the world’s attention, few noted the significance of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s January 18 visit to Israel—the first by a Japanese PM in over a decade.

And that’s a mistake, because the trip’s goal of improving ties between the two countries is vital to the national security, foreign relations, and economic well-being of both countries. It is a potentially major shift in both policy and perspective for two of the most economic and geopolitically important countries in the Middle East and Asia.

There are good reasons for this shift: Both Israel and Japan face very similar challenges in a changing and, indeed, decaying international system. For Israel, Arab and Islamic countries have been manipulating the international system for decades in order to undermine the Jewish State. They have pieced together an influential coalition of countries and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to assist them. As a result, so-called human rights institutions at the United Nations have been taken over by undemocratic, theocratic, and grotesquely oppressive countries, often enabled by anti-Israel and sometimes anti-Semitic NGOs. The result is that the international system set up to protect human rights has been co-opted by many of the worst human rights abusers, allowing despots and fanatical terrorist groups to spread instability, death, and poverty throughout their lands.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu greets his Japanese counterpart Shinzo Abe at the Japan-Israel Business Forum, held at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in Jerusalem, January 18, 2015. Photo: Miriam Alster / Flash90

For Japan, the threat comes from a much larger phenomenon: Countries like China and Russia are systematically undoing the mechanisms that protect national sovereignty and legitimizing a strategy of grand theft territory by undermining values like the right to self-determination and secure, defensible borders. They are successfully pursuing subversive territorial land and sea grabs, such as Russia’s success in quite literally stealing significant parts of Ukraine. Japan is also a primary target of these ambitions. Its success in annexing Crimea has emboldened Russia to step up coercive military pressure on Japan to cede control over the Kuril Islands. China is pursuing a similar strategy toward other Japanese territories.

Due to this systematic effort led by the foes of Israel and Japan, a truly frightening deterioration of international norms is taking place. At the same time, America is taking a step back from principled leadership and Europe is becoming increasingly feeble. Neither seems ready or willing to arrest this deterioration of the international order.

All of this helped lead to Abe’s visit to Israel, which was an official statement of Abe and Netanyahu’s intentions to diversify their foreign relations as a hedge against their enemies’ tactics, boost their economic ties, and build support for their respective security postures. This does indeed represent a major shift in both countries’ foreign policies. Japan has never supported Israel to the extent that many other countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development have. But now both Israel and Japan are facing a situation in which their adversaries seem to be successfully tipping the scales against them, and they need each other to arrest this threat to their national interests.

This is not simple posturing. These seemingly unnatural allies do in fact have much to benefit from cooperation with each other, and contrary to assumptions, their path toward an alliance is not only important, but quite natural indeed. Both countries appear to understand this. Abe did not arrive in Israel with 100 government officials and heads of Japanese companies for nothing. Abe seems to recognize that a sound Middle East policy includes close relations with Israel. And Netanyahu sees the importance of diversifying Israel’s foreign relations and economic ties, as well as the positive role Japan plays in the world and the opportunities presented by a stronger relationship with it.

In order to understand how Abe came to visit Israel and why the trip is so important to the future of both countries, we need to understand why Abe has become the most-traveled Japanese prime minister in history; indeed, one of the most-traveled leaders of any country. In the two years before his visit to Israel, Abe visited more than 50 countries. There is good reason for this.

Like Netanyahu, Abe is on his second go-around as Japan’s leader. During his six-year absence from the prime minister’s office, Abe watched as Japan lost significant economic and diplomatic clout. Once considered an economic miracle, Japan has slipped from second to third on the list of the world’s largest economies, while its geopolitical influence has waned in the face of economic stagnation and China’s rise to the status of regional hegemon.

Upon his return to power, Abe set out to achieve three goals: improving Japan’s economy, national security, and diplomatic position. As a result, Abe has pushed through major economic and security reforms, and embarked on his unprecedented round of diplomatic travel. According to the Carnegie Endowment’s James Schoff, Abe is seeking to sell Japan as a country relevant to global policy issues like technology, the environment, diplomacy, economics, and security. In so doing, Abe is working to make Japan relevant, even though it cannot be as militarily active as other nations. Part of Abe’s pitch to foreign leaders is that Japan is a better partner in Asian trade and diplomacy than China, and the leading representative of Asia in the international community.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe meets with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at his office in Jerusalem, on January 19, 2015. Photo: Kobi Gideon / GPO / Flash90

Abe has now brought this important message to Israel. Until his visit, Israel’s relationship-building efforts with China dwarfed those with Japan, not an unexpected phenomenon given that, in 2013, Israeli exports to China outstripped exports to Japan by a factor of four. Yet, as mentioned above, China—along with Russia—is the preeminent opponent of the international system of economic, security, and legal institutions that, despite their frequent anti-Israel bias, are critical to the maintenance of international order, security, and the promotion of economic and social prosperity around the world. Rising tides lift all boats, even Israel’s, just as a receding one beaches them. As Abe blitzes capital cities, he has to counteract China’s growing influence by making a special effort to convince every leader he meets that Japan’s growing activism on security matters in Asia should be a welcome development. Tellingly, not many leaders have refused.

Abe’s selling of Japan as a better alternative to China furthers his three goals. By standing up for international standards and the benefits of a well-functioning system, he presents Japan as the more trustworthy and constructive partner, and sends the message that Japan stands behind and for a global order in which all countries will be safe, secure and prosperous. The same cannot be said for China. This makes Japan appear to be a more stable economy to invest in and trade with, a more trustworthy security partner, and a more reliable diplomatic ally.

Netanyahu’s concerns are quite similar. He has put a lot of time and effort into expanding Israel’s network of foreign relations for similar reasons. Part of Abe’s motivation for working to secure international norms, for example, is Japan’s export-driven economy. Because the country relies on international markets, the international framework that regulates the global economy is critically important to Japan’s future. Israel’s private sector is also reliant on export markets, and since its domestic consumer economy is dependent on inexpensive imports, it will find that the economic components of the international system often overlooked by Israel’s supporters are critical to its future, as well.

Israel is waking up to this reality as it deals with the shrinking European economy (a key export market), the economic threat from the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement, and growing political isolation. Israeli companies export a lot of product and talent, and Netanyahu has responded by working hard to open more foreign markets to Israeli exports, especially in Asia. The numbers speak for themselves. In 2014, according to statistics from Israel’s Economics Ministry, Israel probably exported more to Asia than to the U.S. By 2018, the ministry projects, a full 25 percent of Israel’s exports will go to Asia.

Netanyahu is intent on expanding these economic ties. In January, he told his cabinet that over “the last two years, I have met with the leaders of China, Japan, and India as part of a comprehensive policy of turning to major markets, including Latin America and Africa.” At that meeting, the cabinet approved a plan calling for the opening of an Israeli trade office in Osaka, Japan, increasing the number of commercial attaches in Tokyo, increasing joint research grants by 50 percent in 2015, increasing cooperation on space programs, and increasing Japanese tourism by 45 percent in two years. He seems to have realized that Japan can be a fruitful partner in Israel’s high-tech sector, an example of how to build an industrial base, a market for Israeli high-tech products, and a source of tourism. While Japan will never supply consumer goods as inexpensive as those from China, it seems that Israel’s political leaders are hearing Abe’s message.

Indeed, on the very day Abe arrived in Israel, Netanyahu let everyone know why he is paying special attention to Asia. “Western Europe is undergoing a wave of Islamization, of anti-Semitism, and of anti-Zionism,” he said, “and we want to ensure that for years to come the State of Israel will have diverse markets all over the world.” Japan is a very appealing part of Netanyahu’s diversification policy.

But improved trade relations and greater investment are not the only reasons for Netanyahu’s hospitable reception of Abe. In particular, Japan and Israel face eerily similar security threats and challenges to their sovereignty and territorial integrity. Readers of The Tower are well aware of Israel’s challenges in this area: Homegrown terrorism, Hamas, Hezbollah, Iran, Turkey, the anti-Israel UN bloc, etc., etc. As a member of the international community, Israel is often and unfairly treated as a pariah state, which also harms Israeli security. And because the legitimacy of Israel’s borders is disputed by its neighbors and most other countries to one degree or another, Israel cannot not sit comfortably in its own home.

Japan’s security concerns are increasingly similar. This is a relatively new development. Until the last few years, it seemed clear that Japan’s borders were recognized by all its neighbors. But as China and Russia became rich and realized that they could successfully flout international laws and conventions, China has begun to make claims on Japan’s Senkaku Islands, while Russia has done the same in regard to the Kuril Islands. The absurdity of these positions—China did not care about the Senkakus until oil was discovered under them, while Russia has repeatedly turned down Japan’s suggestion of international arbitration while ramping up military overflights—is matched only by the weak stand against Russian and Chinese aggression taken by the international community.

Members of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces train at Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni. Photo: United States Marine Corps / Wikimedia

In response, Japan is moving away from the pacifist policies that have guided the country’s foreign policy since World War II, when it was forced to sign the Potsdam Declaration and accept that it could no longer maintain an offensive military. In the nearly 70 years since Potsdam, Japanese society has internalized its posture as a pacifist nation that promotes peace by refusing to fight wars and maintaining a “Japanese Self-Defense Forces” that is constitutionally prohibited from offensive operations. In fact, Article IX of the Japanese constitution prevents Japan from attacking a foreign military—even to protect an ally—except in self-defense, and until recently refrained from establishing a national security council. Japan reinforced this posture by contributing to many international peacekeeping efforts, conflict resolution mechanisms, and human development programs around the world. As a result, Japan has a sterling reputation as a responsible nation that helps create stability and plays by internationally recognized norms.

None of this has changed in the sense that Japan remains and intends to remain a country that contributes to international security and prosperity. But the manner in which Japan is responding to rising threats to its security and sovereignty is changing significantly. Abe, and with him a small but growing number of Japanese, feel that Japan can no longer ensure its security with a purely defense-oriented military, a prohibition on protecting allies, and the lack of a national security council. As a result, Abe has initiated a series of significant improvements to Japan’s already advanced defense forces, secured cabinet approval of a reinterpretation of Article IX that allows Japan’s military to fight in the defense of allies, established a national security council, introduced security and intelligence reforms, opened up Japan’s defense industry to international research and development efforts, and dramatically increased Japan’s operations against cyber-terrorism. In addition, after a decade of declining military budgets, Japan is set to increase defense spending for the third year in a row.

Supporters of Israel rally in Tokyo, July 31 2014. Photo: Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs / flickr

These efforts involve growing collaboration between Japan and Israel. The two countries are already part of the F-35 fighter plane program and signed an agreement on cyber-security cooperation last year. Ongoing changes in Japanese security policy make it very likely that these ties will expand. Both countries have world-class domestic defense industries and access to the American and European defense markets, and are thus entering their partnership on equal terms, which bodes well for a productive future in this area.

Another major factor in Abe’s outreach to Israel is that, as he works to make Japan internationally relevant again, he has taken a particularly strong interest in the Middle East. As will be discussed below, this is due in large part to Japan’s current reliance on imported energy. But it is also motivated by Abe’s especially deep understanding of the impact of Middle East instability and conflict on the international system.

Speaking to the Japan-Egypt Business Committee in Cairo on January 17, for example, Abe spoke of “the stability of the Middle East” as “the foundation for peace and prosperity in the world, and of course for Japan.” He explained Japan’s approach to the region as one that “always aims at no less than restoring stability in the region,” because Japan’s “unwavering path” in foreign affairs “is one adhering to peace.” To this end, he reminded the crowd of his pledge two years prior to commit $2.2 billion in assistance to the region. He then pledged an additional $2.5 billion in non-military aid. He also spoke of his government’s active role in the peace process. For example, among other efforts, Japan facilitates agricultural cooperation between Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinians. As I have previously written in The Tower, agriculture plays a very positive role in Israeli-Palestinian relations, and the Israeli government and Palestinian agriculture professionals go to great lengths to make the most of these cooperative programs.

Abe concluded his speech by saying the “world will be truly blessed when the Middle East steadily takes the enormous step, aiming at tolerance rather than hatred, and embracing moderation.” Abe appears to believe that so long as the Middle East simmers and is used by world powers to wage proxy wars and challenge each other’s commitments and influence, the international system will be undermined, making Japan increasingly unsafe.

ISIS captured Japanese citizens Kenji Goto and Haruna Yukawa and held them as hostages. Photo: CBC News / YouTube

Another influential factor in Abe’s attention to the Middle East is the rise of ISIS. The rising prevalence of “foreign fighters” traveling to Syria and Iraq in order to fight for ISIS was the first element to catch Abe’s attention. There are an estimated 100,000 Muslims living in Japan; a few have shown support for ISIS, and some are believed to have at least attempted to join the terrorist group. In October of 2014, Japan made its first ISIS-related arrest, detaining a university student suspected of planning to join ISIS in Syria. A few weeks prior, a former chief of Japan’s air force quoted Israel’s Foreign Ministry Director-General as saying that nine Japanese have already joined ISIS. While this report has yet to be confirmed, the deadly threat posed by returning foreign fighters has been made obvious in Europe, and Abe is paying close attention to it.

The full depth of the ISIS threat has become epitomized by the hostage crisis that coincided with his visit to Israel. While in Israel, ISIS released a video of two Japanese nationals it had captured, and demanded $200 million in ransom. This number was likely chosen by ISIS because it matched a commitment worth $200 million Abe had just made to help its allies fight the group. When Abe refused to pay the ransom and his government’s efforts to secure the release of the hostages failed, ISIS executed both men. This series of events has touched off a debate in Japan, with Abe and his allies arguing that the tragic situation made clear that Japan’s military needs to be able to operate abroad in order rescue Japanese citizens from emergency situations. His opponents draw a cause-and-effect connection between Abe’s support of the anti-ISIS campaign and ISIS’s cruel acts against the two Japanese hostages to argue that Japan should remove itself from the international coalition against ISIS.

Japan’s intelligence operations in the Middle East are not robust, and if Japan is to be able to more effectively handle a terror-related threat against its citizens it the future, it has much to learn. Closer relationship with the Israeli intelligence and military communities will go a long way in sharpening Japan’s ability to combat the threat of terrorism. Abe has already committed some $200 million in helping its allies fight ISIS, and another $7.5 million in broader counter-terrorism efforts in the Middle East and North Africa. The hostage crisis may end up spurring deeper investments.

A final area of potential Japanese-Israeli cooperation is energy. While both countries have always needed to import petroleum products, the two countries have recently begun moving in opposite directions in terms of energy supply. Until the March 2011 tsunami knocked out Japan’s nuclear industry, Japan was able to generate about a quarter of its domestic energy needs with nuclear power. Following the disaster, the Japanese public turned decisively against nuclear energy. As a result, Japan has become the world’s largest importer of liquefied natural gas. Natural gas is not only significantly more expensive that nuclear energy, but Japan’s reliance on it has dramatically worsened its energy security. As a result, within his first nine months in office, Abe visited seven major energy-producing countries, hoping to diversify Japan’s imports—Russia, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar, the United States, and Canada. Of these seven, the only countries that do not tend to make life difficult for an energy client are the U.S. and Canada. But Japan’s energy needs are significant enough that Abe has been forced to court such dubious figures as Vladimir Putin and the Saudi royal family.

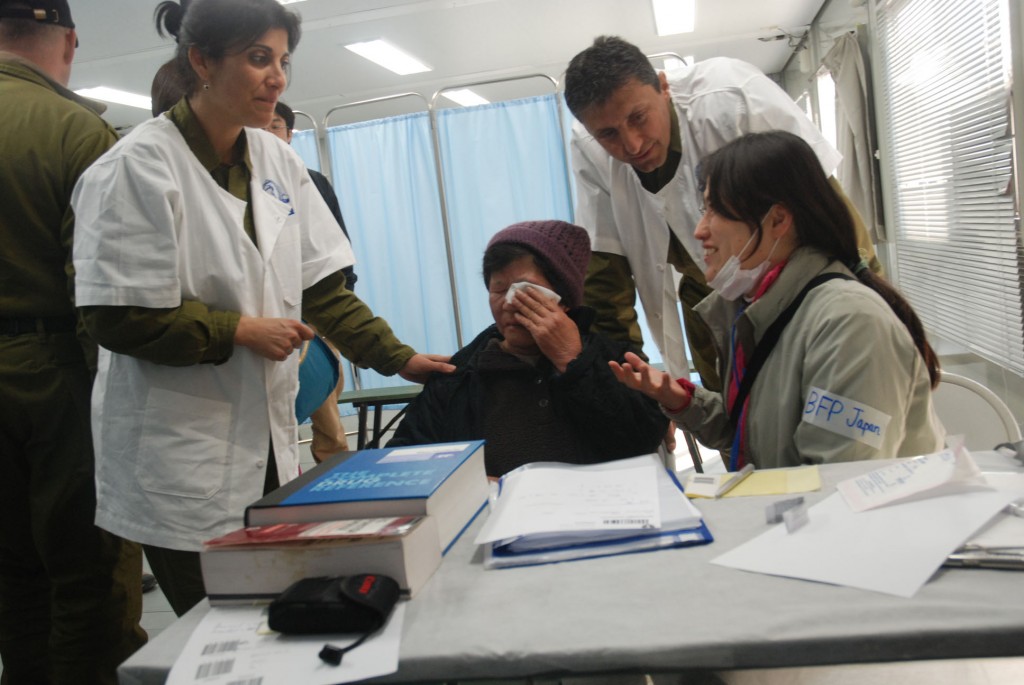

An Israeli medical delegation traveled to Japan to assist after the devastating earthquake and tsunami in 2011. Following publications in Japanese news outlets regarding the opening of an Israeli medical clinic in Minamisanriku, Setsukao Yamauchi, an 80-year-old woman, walked three hours from her distant village to be treated by Lt. Col. Dr. Orly Weinstein, an Israeli eye specialist. Photo: Israel Defense Forces / Wikimedia

Israel, on the other hand, has seen a major shift in its favor in terms of energy supplies. After the discovery of large reserves of natural gas in its territorial waters, Israel has gone from an importer of natural gas to a domestic producer. While Israel’s energy sector is going through a difficult maturation and domestic energy prices have yet to decline, Israel has been quick to leverage its new supplies to serve foreign policy goals. Export deals with the Palestinians and Jordanians, although not yet enacted, stand to increase Israel’s influence and, hopefully, improve relations as well. Israel may be able to extend this strategy to Egypt over the long term. And because they have discovered abutting natural gas fields, the relationship between Cyprus and Israel has significantly strengthened through a major expansion in cooperation. In short, Israeli natural gas has made Netanyahu a slightly more attractive partner to his neighbors.

While it does not appear that energy was on the agenda during Abe’s visit, both countries are experts in natural gas and the ramifications of poor energy security, and have the same interest in building a more secure and affordable global energy market. While it is unlikely that Israel will build a liquefaction terminal in Eilat to ship natural gas to Japan, Japan’s diplomatic standing can help Israel export its natural gas to the European market, helping to stabilize Europe’s energy security. This, in turn, would aid Japan by reducing the amount of gas sent to Europe by some of Japan’s suppliers, improving the energy market to Japan’s advantage.

So, on economic, security, diplomatic, and energy issues, a closer relationship between Israel and Japan promises major benefits to both sides. With many Western countries moving away from unqualified support for Israel, the importance of Japan is growing, creating an urgent need for Israel to tighten cooperation and formalize an expanded relationship.

Japan’s partnership and support will not come free of political and diplomatic disagreements, however. Japan has built its global reputation by embodying the values driving the international system that Israel is often accused of violating, and thus cannot become an uncritical supporter of Israel. But in the context of Japan’s growing identification with the challenges Israel has always faced, Japan’s favorable place in the international system is exactly what can make a closer relationship with Israel so helpful.

Japan’s international reputation is a double-edged sword, however, as evidenced by the joint press conference held during Abe’s visit. Both leaders agreed on a great deal: The importance of combating terrorism, anti-Semitism, anti-democratic forces, Iran’s nuclear weapons program, and even the Palestinians’ bid to use the International Criminal Court against Israel (Abe said he would push Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas to halt his campaign to do so). But on the issue of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as a whole, they diverged, and Japan showed the importance it places on maintaining a neutral position on this highly controversial topic. As Abe well knows, taking a strong pro-Israel position would significantly undermine Japan’s reputation in the international community and the weight it carries on many other issues of great significance.

In an op-ed published in Yediot Aharonot, Israel’s largest Hebrew daily, Abe emphasized the importance of a negotiated two-state solution and bemoaned the collapse of recent peace talks, as well as Israeli settlement building. He warned that the issue could trigger international isolation and recommended that Israel and the Palestinians refrain from actions that make peace less likely. While Japan is on the same side as Israel on maintaining international support for the right of nations to self-defense and territorial sovereignty, Abe does not appear interested in applying these principles to the most controversial of Israel-related issues.

That said, Netanyahu knows he cannot win a favorable solution to Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians from the international community, even if Japan takes his side; and he is not particularly interested in seeing the conflict play out in that sphere in any case. What matters to Netanyahu are the many issues on which there is confluence with Japan. If Israel can maximize this opportunity, it can offer help on some of the challenges outlined above, leverage the lessons Japan has to offer, and pursue the opportunities offered by a better relationship with Japan. Due to Japan’s diplomatic standing, this would help earn recognition of Israel’s legitimacy and an endorsement of its positive aspects, something Israel currently enjoys from precious few countries.

A better relationship between the two countries means Israel can ask Japan for help and advice on how to better integrate itself into the international system and make the system work for Israel, or at least mitigate the damage it can do. It means that as America withdraws from the Middle East, Israel picks up support from another major player that does not carry the often negative reputation America has among Israel’s detractors. It means that Israel has a strong ally against Chinese and Russian-led efforts to undermine the international system and norms of sovereignty, national legitimacy, and human rights; something that places Israel in increasing danger. It means that if Europe does move toward some form of BDS or continues to shrink economically, Israel has the option of turning to another major international market in an increasingly important and wealthy Asia. These are all positives, and they do not come at the cost of other relationships. In today’s swiftly changing and, in many ways, unraveling world, Japan and Israel are natural allies.

![]()

Banner Photo: Noam Moscowitz / Flash90