Far from being the death-knell of Israeli democracy, the proposed “Jewish State” legislation—which was first promoted by the Center-Left Kadima party in 2011—should be seen as a fulfillment of Israel’s democratic tradition, and a continuation of the international events that give the country legitimacy—even if it never passes.

“Accordingly, we … hereby declare the establishment of a Jewish state in eretz yisrael, to be known as the State of Israel.” Anyone following the news lately would probably assume that this is a quote from the Jewish State Bill, proposed by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. In fact, it’s an excerpt from Israel’s Declaration of Independence, written by David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister and head of the Left-wing Mapai party, and declared by him on the eve of Israel’s independence, on May 14, 1948. Yet, even though its content is not appreciably different from Ben-Gurion’s declaration, analysts and politicians have been in an uproar over the Jewish State Bill, attacking it as a radical threat to Israeli democracy.

In fact, the actual language of the various recently proposed bills is remarkably innocuous. The legislation seeks to officially reaffirm the character of the State of Israel—“a Jewish and democratic state in the spirit of the principles of the Declaration of Independence”—as the national state of the Jewish people. This may seem redundant, but due to the intricacies of Israeli law, it is not. An affirmation both of democracy and reality, such legislation is important as a complement to Israel’s Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty, which defines Israel’s democratic character, so that neither characteristic prevails over the other. “Both of these values are equal and both must be considered to the same degree,” says Netanyahu. In other words, at a time when Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish state is under unprecedented attack, all the “Basic Law: Israel as Nation State of the Jewish People” does is summarize and enshrine these realities in a single basic law.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu addresses the Knesset on the Jewish State Bill, November 26, 2014. Photo: Miriam Alster / Flash90

In order to achieve this, the bill brings together all the various legal aspects of Israel’s unique Jewish existence. It describes the Land of Israel as the Jewish people’s “historic homeland” and “national home” where they realize their “right to self-determination in accordance with its culture and historic heritage,” making the right to self-determination in the State of Israel “unique to the Jewish people.” Just as instruments of international law (particularly Articles 6 and 7 of the Palestine Mandate), the Declaration of Independence, and the 1950 Law of Return (also signed into law by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion) grant Jews special immigration rights to the State of Israel, so too does the Bill declare that “all Jews are eligible to immigrate to the country and receive citizenship of the state according to law,” and that the State would act to gather the exiles of the Jewish people. The bill binds Israel to act in assistance of Jews being persecuted because of their identity. It makes the State’s mission the preservation and cultivation of “the historical and cultural heritage of the Jewish People,” obligating all educational institutions to “teach the history, heritage and tradition of the Jewish people.” It makes Jewish law a source of inspiration for Knesset legislation, and allows courts, in the absence of “legislation, precedent or clear inference,” to draw on the “principles of freedom, justice, fairness and peace of the heritage of Israel.” Like other democratic constitutions, it defines the country’s national anthem (“Hatikva”), flag, and coat of arms. It makes the Hebrew calendar the official state calendar, and defines Yom Ha’Atzmaut (Independence Day), Yom Ha’Zikaron (Memorial Day for Fallen Soldiers), and Yom Ha’Shoah (Holocaust Memorial Day) as official state holidays, marking Jewish holidays and the Sabbath as be public holidays, but “the country’s public holidays.”

The bill also defines Israel as a democratic state, bound to uphold the fundamental freedoms and individual rights of its citizens according to law. As a democratic state, Israel will also “act to enable all residents of Israel, regardless of race or nationality, to preserve their culture, heritage, language, and identity.” The bill also protects all holy places against desecration or any damage that might negatively affect worshippers’ access to these sites or their feelings, and grants “members of recognized faiths [the right] to rest on their Sabbaths and holidays,” paralleling Article 23 of the Palestine Mandate. Finally, like the other Basic Laws, it disallows any infringement on individual rights, except by a law that “befits the values of the State of Israel…designed for a worthy purpose” and which is not excessive. As a point of comparison, in U.S. Constitutional law, such a law would have to be “narrowly tailored,” use the least restrictive means and be justified by a “compelling governmental interest.” It would have to pass the most stringent standard of judicial review used by U.S. courts, known as “strict scrutiny.”

All of this is in keeping with both Israeli and international law, as well as the basic political norms most Western countries apply to themselves.

Nonetheless, the non-controversial concepts enshrined in this bill have come under scathing and overwrought attack, based on straw-men arguments unconnected to the bill’s actual language, or based on now-rejected draft proposals. Israeli-Arab writer Sayed Kashua, for example, claims the bill is “intended to ensure that when the Jewishness of the state clashes with equality, the Jewish nature of Israel will prevail rather than democracy.” The purpose, he says, is to make Israel “exclusively for Jews and only for Jews,” a place where “people are separated by race.” Left-leaning scholar Bernard Avishai has said that the bill is “not really about conserving collective cultural rights, but rather about confirming individual legal privileges.” He claims it is Netanyahu’s attempt to damage individual and minority rights and curtail Israel’s judiciary. He concludes that the bill forces Israel to choose whether it wishes to be a “globalist Hebrew republic or a little Jewish Pakistan.”

Many respected media outlets have also attacked the bill in vitriolic terms. The Sunday Times’s headline on the subject was “Israel Set to Make Arabs ‘Second-Class Citizens.’” An emotional Wall Street Journal op-ed claimed the bill demeans the standing of Israelis like the heroic Druze police officer Zidan Saif and “betrays the most fundamental principles in the Israeli Declaration of Independence.” The New York Times titled its editorial on the bill “Israel Narrows Its Democracy,” calling it a Right-wing initiative contrary to “Israel’s very existence and promise [that] has been based on the ideal of democracy for all its people,” even implicitly tying it to segregation in the pre-Civil Rights American South.

The Jewish State Law is acceptable under both Israeli and international law, as well as under the basic political norms most Western countries apply to themselves.

Western diplomats have also voiced their concern. Senior European Union officials said they have taken note of it, and expect Israel to “recognize and respect” its longstanding democratic principles. U.S. State Department spokesman Jeff Rathke said that the United States “would expect any final legislation to continue Israel’s commitment to democratic principles. … The United States’ position … is that Israel is a Jewish and democratic state in which all citizens should enjoy equal rights.” German Foreign Ministry Spokesman Martin Schaefer noted his country’s “wish and expectation … that the rights of ethnic, religious and all other minorities in the Middle East … are taken into consideration and their rights are ensured. That is one of the biggest problems in the region that is not really achieved in many states, including Iraq. But that is also the case in other states, here I am explicitly referring to Israel.” Many Western embassies in Israel received repeated inquiries from their home countries in regard to the bill, asking why it was needed and what the implications for the Israel-Palestinian peace process might be. The Dutch ambassador to Israel, Caspar Veldkamp, said the West was closely following the debate on the bill and expected “Israel to continue to live up to its democratic ideas and practices.”

This widespread concern, misrepresentation of the idea, and manufactured outrage, is all the more ridiculous when one recognizes that the bill’s conception is not an idea of the Right, or the Likud, or the current government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. In fact, the bill itself originated with MK Avi Dichter of the Center-Left Kadima party back in 2011. But the bill’s vision of Israel as a Jewish state is much older, rooted in the instruments of international law which gave rise to the State of Israel itself.

The Jewish state’s rebirth was the result of the Jewish people’s physical and legal assertion of their national right to self-determination in their ancient homeland, and the international community’s de jure recognition of that right. Being a Jewish State was, and remains, the reason for Israel’s existence under international law.

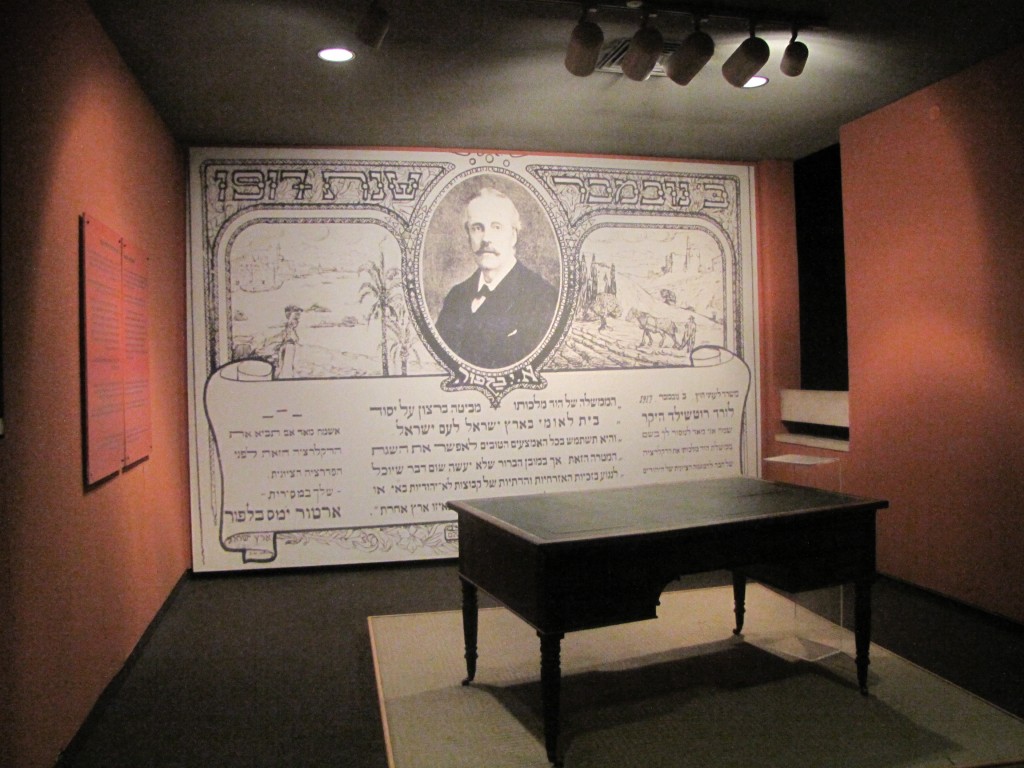

The first official recognition of the Jewish people’s right to a state in the Land of Israel long predates Israel’s establishment. It was given by Great Britain on November 2, 1917, in the form of the Balfour Declaration. Though not a binding instrument of international law per se, the Declaration was important because it was the first time a modern great power recognized the Jewish people’s continuing historical connection to the land and their right to reconstitute themselves as a nation in that territory, then under Ottoman control. It conveyed Britain’s favorable view toward “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people,” and pledged to facilitate that establishment. While the Declaration pointed out the necessity of protecting “the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine,” historian Anita Shapira noted that this refers “not to national rights, but only civil and religious ones.”

Lord Balfour’s writing desk, now located at Beit Hatfutsot – The Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv. Photo: Ziko / Wikimedia

Leopold Amery, a Secretary to the British War Cabinet of 1917-18, testified under oath to the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry in January 1946 that the phrase “national home for the Jewish people” “was intended and understood by all concerned to mean at the time of the Balfour Declaration that Palestine would ultimately become a ‘Jewish Commonwealth’ or a ‘Jewish State,’ if only Jews came and settled there in sufficient numbers.” In his Memoirs of the Peace Conference, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George confirmed Amery’s understanding, noting that the Declaration was intended to make Palestine a “Jewish Commonwealth” when the Jews became a majority of the country’s population, criticizing as “unjust” and “a fraud” the subsequent artificial restriction of Jewish immigration by British authorities intended to keep them a minority in Palestine.

Britain was not alone in supporting this endeavor. The Declaration’s promise of a Jewish State was “issued with the approval of the United States and France, and after consultation with Italy and the Vatican, and greeted with the approval by the public and press throughout the western world,” notes historian David Fromkin. Lloyd George’s Memoirs notes President Woodrow Wilson explaining the Declaration to the American public, noting that, “the Allied nations, with the fullest concurrence of our Government and our people, are agreed that in Palestine shall be laid the foundations of a Jewish Commonwealth.”

On April 24, 1920, at the San Remo Conference, the Supreme Council of the Principal Allied Powers gave the provisions of the Balfour Declaration the status of international law, and recognized the Jewish people’s right to establish a nation-state in Palestine. The San Remo Resolution made the establishment of a Jewish state an international legal obligation. It devolved this obligation onto the designated ruler of “Mandatory Palestine.” The Council did not intend to satisfy Arab national claims or rights to self-determination in Palestine, as it had already created and designated Syria and Mesopotamia for that purpose.

The San Remo Resolution also provided that the creation of a Jewish State “would not involve the surrender of the rights hitherto enjoyed by the non-Jewish communities in Palestine,” which did not include national rights or self-determination. Those rights were suppressed under Ottoman imperial rule. The Resolution explicitly states that Palestine would be entrusted to a Mandatory power to put into effect the Balfour Declaration’s demand for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people,” without prejudicing “the civil and religious rights [emphasis own] of existing non-Jewish communities…”

Understanding the phrase “civil and religious rights,” is essential to understanding the rights of Palestine’s non-Jewish communities as envisioned under international law. The minutes of the San Remo Conference meeting on the evening of April 24, 1920 explain the phrase’s meaning. A disagreement, over form rather than substance, arose between French Prime Minister Alexandre Millerand and British Foreign Affairs Secretary Lord George Nathaniel Curzon over the phrase. Millerand complained that “civil and religious rights,” was insufficient, and proposed adding the explicit mention of the additional “political rights” of the non-Jewish communities, by which he meant the right to vote and take part in elections. Lord Curzon rejected the change as unnecessary, since in British law such rights were included under “civil rights.” In drafting the San Remo Resolution, the rights guaranteed to Palestine’s non-Jewish minorities were individual civil and religious rights. The international community did not envision collective political rights – i.e. the right to self-determination – being granted to Palestine’s non-Jewish communities.

The international community has long recognized the Jewish people’s right to self-determination.

The Council of the League of Nations subsequently appointed Great Britain the ruler of Mandatory Palestine, beginning on September 29, 1923. Fromkin notes that the Balfour Declaration’s call for a Jewish state in Palestine “was embodied in the League of Nations Mandate entrusting Britain as trustee of Palestine with the mission of creating a Jewish National Home while protecting the rights of non-Jews as well….” Fromkin’s understanding is confirmed by the Mandate’s preamble, which explicitly states that Britain was given Mandatory powers in order to enact the Balfour Declaration, based on the “recognition … given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine and to the grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country.” No such promise was made to the Palestinian Arabs. Per Article 80 of the United Nations Charter, the Palestine Mandate has continuing validity under international law, and Israel’s Supreme Court considers the Mandate, in its entirety, as binding law upon itself.

Article 2 of the Palestine Mandate incorporated the Balfour Declaration’s promises and meaning, charging Britain with the responsibility for “placing the country under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of a Jewish national home…and also for safeguarding the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine, irrespective of race and religion.” Article 6 required Britain to “facilitate Jewish immigration,” to Palestine and “encourage…close settlement by Jews on the land,” and Article 7 stipulated the creation of a nationality law for Palestine which would include “provisions framed so as to facilitate the acquisition of Palestinian citizenship by Jews.”

For various reason, the British repeatedly attempted to revise the terms of the Mandate’s territorial scope. However, even these subsequent attempts at revising the Mandate still adhered to the principle of establishing a Jewish state in Palestine. The 1936 Peel Commission Report, one of the first attempts at revising the Mandate, recommended the partition of Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states. The report noted that partition would grant Palestine’s Arabs “national independence” in their own state; but at the same time, it acknowledged that “partition secures the establishment of the Jewish national home and relieves it from the possibility of being subjected in the future to Arab rule.” This, the Commission stated,

Enables the Jews in the fullest sense to call their National Home their own: for it converts it into a Jewish State. Its citizens will be able to admit as many Jews into it as they themselves believe can be absorbed. They will attain the primary objective of Zionism—a Jewish nation, planted in Palestine, giving its nationals the same status in the world as other nations give theirs. They will cease at last to live a “minority life.”

The next recommendation for partition came from the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) report, submitted to the UN General Assembly on September 3, 1947. It also recommended “the creation of a Jewish state under a partition scheme” in Palestine, ruling out the possibility of a binational state.

Following UNSCOP’s recommendations, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 181 on November 27, 1947, which formally partitioned the territory. It stated that, after the termination of the British Mandate, an “independent Arab and Jewish State … shall come into existence in Palestine.” While it called for the protection of the human rights of minorities in both states, it did not mention national rights or rights of self-determination for these groups. The national rights of the Palestinian Jews would be realized only in the Jewish state, and vice-versa. The section entitled “Religious and Minority Rights” guarantees freedom of conscience and worship, prohibits discrimination based on race, religion, language or sex, and enjoins equal protection of the laws and protection of the personal status of minorities and adequate provisions for minority education for each community, “in its own language and cultural traditions…while conforming to such educational requirements of a general nature as the State may impose.” But it does not mention national rights or rights of self-determination for minority groups. Finally, the Resolution’s citizenship law, intended to maintain Jewish and Arab majorities in their respective States after Partition, stated that in the transitional period until each State’s independence, “No Arab residing in the area of the proposed Arab State shall have the right to opt for citizenship in the proposed Jewish State,” and vice versa. The Arab and Jewish States were not required to uphold the national rights or right to self-determination of their respective minorities.

Thus, over the decades leading up to the independence of the State of Israel, international law encouraged and legally required the establishment of a Jewish state. Its proviso that a Jewish state should ensure and protect the civil, political, and legal rights of its non-Jewish minorities did not negate this. In fact, it strengthened it—as it would in the modern version of the conception currently under consideration—since it implicitly stated that international law did not see any inherent contradiction between such a state’s Jewish and democratic character.

David Ben-Gurion testifies at the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry, 1946. Photo: Harvard University Library / Wikimedia

Neither did Israel’s Declaration of Independence contain any such contradiction. It declares Israel a Jewish state that will “ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex; it will guarantee freedom of religion, language, education and culture; it will safeguard the Holy Places of all religions; and it will be faithful to the principles of the Charter of the United Nations.” It also called on Israel’s Arab citizens to “participate in the upbuilding of the State on the basis of full and equal citizenship and due representation in all its provisional and permanent institutions.”

At the same time, the Declaration asserts that the State of Israel is a Jewish state in no uncertain terms. Quite explicitly, the Declaration calls the Land of Israel “the birthplace of the Jewish people,” where their religious and political identity was shaped and where they first attained statehood. It further notes that Theodor Herzl’s efforts led to the resurrection of “the right of the Jewish people to national rebirth (tekuma leumit) in its own country.” Israel’s raison d’être was to be a Jewish state in the Jews’ “national homeland” that “would open the gates of the homeland wide to every Jew and confer upon the Jewish people the status of a fully privileged member of the community of nations.” The internationally recognized right of the Jewish people to “establish their state”—in other words, their right to self-determination—“is the natural right of the Jewish people to be masters of their own fate, like all other nations, in their own sovereign state.” It was on this basis that President Harry Truman granted de jure American recognition to the newborn State of Israel.

While the Declaration is neither law nor an ordinary legal document, it has legal standing in Israeli law. The third section, describing the democratic principles that guide the State of Israel, has been used by the Supreme Court for the purpose of normative interpretation. The second section, which declares the establishment of Israel as a Jewish state, is the primary source of authority in the Israeli legal system. Given that the Jewish State Bill endorses and echoes both of these sections, it cannot be called a radical revision of Israel’s Jewish or democratic character.

Basic Law: Israel as the Nation State of the Jewish People conforms to international law and Israel’s Declaration of Independence. This leaves the question of whether the bill, if passed in one of its current forms, detracts from Israel’s duties as a democratic nation. Does it interfere with Israel’s obligations to ensure the rights, freedoms, and equality of its non-Jewish citizens? Is a de jure Jewish state inherently anti-democratic?

The bill itself offers the first answer, since it explicitly defines Israel as “Jewish and democratic.” Quoting the Declaration of Independence, it refers to Israel as a state “based on the foundations of freedom, justice and peace in light of the visions of the prophets of Israel” that “upholds the individual rights of all its citizens according to law.”

In accordance with the demands of international law, the bill also guarantees that “the state will act to enable all residents of Israel, regardless of religion, race, or nationality, to preserve their culture, heritage, language, and identity.”

Despite this final guarantee, critics of the bill have emphasized the issue of religious freedom. Bernard Avishai, for example, claims that the bill will result in “the imposition of archaic Jewish law entrenching rabbinic courts and religious commandments as state institutions.” This charge is simply inaccurate and false. Despite the desire of Israel’s harshest critics of itself to use such an argument, convenient to them on various levels, these various legislative proposals would not transform Israel into a theocracy. It cannot be emphasized enough that using Jewish law as a source of legislative or judicial inspiration is not equivalent to making Jewish law the normative source of law in Israel. As the Supreme Court noted in the Cohen and Bousslik v. The Attorney General case, “Jewish law as applied by a civil court is different from Jewish law applied by a religious court. There is a difference in approach, in method, and sometimes in the actual content of the judgment.”

Former president of the Israeli Supreme Court Aharon Barak attends an law convention at Beit Maiersdorf in Jerusalem, January 4, 2010. Photo: Yossi Zamir / Flash90

Proof of this is that drawing on Jewish law is nothing new to Israel’s firmly secular judiciary and legislature. Former Supreme Court Justice David Cheshin notes that Israeli courts, “especially the Supreme Court, turn to…Jewish law on their own initiative, and apply Jewish law in a varied manner, encompassing a wide spectrum of legal institutions and concepts.” The Court occasionally “turn[s] to Jewish law in order to interpret a Jewish legal idiom which appears in original Israeli legislation… [or] when trying to clarify the meaning of a certain legal institution.” The use of Jewish law, however, is dependent upon the judge before whom the case comes and his knowledge of Jewish law. Asher Arian, a senior research fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute, notes that in the rare instances where the Knesset legislates in the field of personal law and “in other matters, Jewish law is often taken into account.”

The bill’s wording, in fact, is lifted verbatim from two laws long since passed by the Knesset: The Courts Law, 5717-1958 and the Foundations of Law, 5740-1980, the latter of which states, “where the court, faced with a legal question requiring decision, finds no answer to it in statute or case law or by analogy, it shall decide it in the light of the principles of freedom, justice, equity, and peace of Israel’s heritage.” According to the highly respected and influential—as well as very liberal—former Supreme Court President Aharon Barak, this phrase means that the law recognizes specific principles derived from Jewish law, rather than Jewish law in general, as a source for judicial decisions absent a relevant statutory or case law. In his ruling on the Bank Kupat Am Ltd. v. Eliezer Handles case, Barak further noted that, while Jewish law is not a source of law per se in the State of Israel, it can be used as judicial inspiration for comparison purposes—much as Jewish law has formed the basis and inspiration of western legal tradition dating back to its earliest origins.

Avishai himself has admitted that the idea of drawing on Jewish law is by no means radical. He noted that the 1983 Kahan Commission, which investigated the Sabra and Shatila massacre in Lebanon, “applied the principle of ‘indirect responsibility,’ derived from a poignant passage in Deuteronomy [21:6-7].” The Commission also made use of Rabbi Yehoshua Ben Levi’s interpretation of a Talmudic passage (Tractate Sotah 38b) and Rashi’s commentary on it.

If anything disproves the claim that the Jewish State Bill is a threat to religious freedom, it is that even though its legislature and judiciary have made use of Jewish law for almost seven decades, Israel is still a fundamentally secular state. The current bill does not change that.

Of course, like all laws, the Jewish State Bill is open to possible abuse. But this risk is minimal, not only due to the provisions of the bill itself, but because of the checks and balances the Israeli legal system has already set in place; in particular, the powers of the Israeli Supreme Court, one of the world’s most highly regarded independent high courts.

Since the 1980s, the Supreme Court—which includes Israeli-Arab justices—has established itself as an activist protector of human rights and the guardian of Israel’s secular identity. It routinely intervenes to promote civil liberties and equality between various sectors of the Israeli population, and acts as a court of first and last instance, exercising judicial review over all branches of government. As Asher Arian notes, Israel’s professional and unpoliticized judiciary is “an important bastion of Israeli democracy,” adding that Israel’s Supreme Court has assumed “the task of major guardian of justice and civil rights in Israel…[and] has developed into a very dynamic actor in the governmental system,” striving to broaden the meaning of justice in Israel, and “ensuring for itself the role of fearless guardian of inherent rights.” The Israeli court system generally is “highly aware of civil rights and respects the tradition of the Enlightenment that places individual rights at the heart of society. The role of the Supreme Court is to protect rights and to limit the authorities in their unwarranted use of power.” When Aharon Barak assumed the Court’s presidency, his concept that “everything is justiciable” made the court even more activist, with a role to fiercely protect the rule of law in a democratic society and keeping the government under the Court’s watchful eye, and subjecting all government decisions to judicial review. This further solidified the judiciary as the defender of individual rights against an executive or legislature that might sideline them in the pursuit of the public good.

While Israel does not have a written constitution (similar to the United Kingdom), the Supreme Court still has a strongly democratic corpus of law to draw upon and which has constitutional status. In accordance with the Harari Proposal of June 13, 1950, Israel’s constitution “will be made up of chapters, each of which will constitute a separate basic law … and all the chapters together [emphasis own] will constitute the constitution of the State.” So far, eleven Basic Laws have been enacted. Several of them give the Supreme Court the power to overturn any cabinet or Knesset decision that violates the rights they enumerate. The Court has made it clear that it is willing to exercise this power. Arian notes that these laws “had a noticeable [restraining] impact on legislators and administrators who had to consider whether their laws or actions would survive the scrutiny of the Court.” Additionally, many of the Basic Laws emphasize the Jewish character of the State of Israel.

Among the Basic Laws the Supreme Court could employ to prevent any abuse of the Jewish State Bill are Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty (1992), which protects the “fundamental human rights in Israel [that] are founded upon recognition of the value of the human being, the sanctity of human life, and the principle that all persons are free.” It requires the state to uphold these rights “in the spirit of the principles set forth in the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel.” This implicitly refers to the Declaration’s aforementioned guarantee of “complete equality of social and political rights to all [Israel’s] inhabitants irrespective of religion, race, or sex,” as well as “freedom of religion, conscience, language, education, and culture.” Basic Law: Freedom of Occupation (1994) guarantees the freedom and rights of all Israeli citizens to any profession they wish by referring to Israel as “a Jewish and democratic state.” Like the proposed Jewish State bill, both of these Basic laws define Israel as “a Jewish and democratic State,” anchoring Israel’s democratic nature in virtually immutable law.

The Israeli Supreme Court building, overlooking the Knesset. Photo: Israeli Ministry of Tourism/ Wikimedia

Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel (1980) provides for the protection of all of Jerusalem’s holy places and guarantees “freedom of access to the members of the different religions to the places sacred to them or their feelings.” It is worth noting that the Jewish State Bill strengthens this protection by guarding the holy places against desecration, damage, or “anything that is liable to infringe on freedom of access by worshippers the places that are holy to them or on their feelings towards those places.” Finally, Basic Law: The Knesset (1958, amended 1985) bans political candidates who negate either that Israel is “the state of the Jewish people” or the “democratic character of the state.

In addition to Israel’s own domestic laws, the Supreme Court can rely on instruments of international human rights law to which Israel is a signatory. Since Israel has yet to adopt a written constitution, international human rights law has affected and critically influenced the development of Israeli constitutional law, and this influence has gradually increased since the late 1990s. According to Hebrew University Law professor Eyal Benevisti, “a canon of interpretation provides a presumption that the Knesset [has] no intention to derogate from the international obligation of the state,” and accordingly, the Supreme Court interprets statutes and other laws “as much as possible to conform with international customary and treaty-based law.” Ruth Lapidoth, Professor Emeritus of International Law at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, concurs that where doubt exists “about the compatibility between international custom and Israeli law, the court will attempt to interpret the law as far as possible so that it may conform with the international rule.” The Supreme Court’s case law presumes the harmony of Israeli law with international custom, and also with “basic principles of equality, freedom, and justice which are the heritage of all civilized, enlightened states.”

Israel has ratified multiple international human rights treaties, incorporating many of their provisions into domestic legislation, including its Basic Laws. The most relevant treaties are the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant of Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD). The Supreme Court has routinely fallen back on these documents in its decisions, as in the Poria Ilit Committee v. Minister of Education and Yated-Association for Children with Down Syndrome v. Ministry of Education cases.

Beyond being an additional bulwark of Israeli democracy, a careful look at the Jewish State bill shows that nothing it contains violates the rights guaranteed in these treaties, inherently or implicitly. In fact, by enshrining the Jewish people’s right to self-determination in constitutional law, Israel would be fully in accord with the ICCPR and ICESCR, which permit countries and peoples to “freely determine their political status and freely pursue … their cultural development” on the basis of that right. In other words, it is Israel’s right under international law to define itself as a Jewish state and protect the Jewish people’s right to self-determination.

Most importantly, the bill’s critics appear to have missed, or purposefully ignored, the fact that the bill’s language actually strengthens Israel’s democratic character. As noted above, many of Israel’s Basic Laws have given Israel’s Jewish identity constitutional status. However, they do not define that Jewish identity, and by failing to do so, they leave it open to endless interpretation and potential abuse. By defining Israel’s Jewish character, the proposed bill also sets limits on it. As Prime Minister Netanyahu has said, the Jewish State Bill should be viewed as complementing and completing these two Basics laws, defining the parameters and outer-limits of Israel’s Jewishness and remedying the other Basic Laws’ oversight. Leaving Israel’s Jewish character open to unlimited interpretation could eventually lead to a genuine threat to Israeli democracy. But by defining it in constitutional terms, the bill gives the Supreme Court the means to ensure that Israel’s Jewish and democratic aspects remain equal and balanced.

Put simply, critics of the bill are not looking at it in the broader context of Israeli law. Instead, they view the Bill in isolation, a misguided view since it not only ignores the bill’s own democratic guarantees and narrow definition of Israel’s Jewishness, but also ignore the Harari Proposal’s requirement of considering the sum of Israel’s Basic Laws to be its constitution, the influence of international law on Israeli constitutional law, and the Supreme Court’s power to interpret this entire corpus of law to prevent any abuse of the bill for anti-democratic purposes.

It is also important to note that Israel is not alone among democratic states in attempting to safeguard its national identity through law. As even Bernard Avishai admits, “Democracies everywhere protect their distinct national cultures and languages.” Indeed, seven European Union states have constitutional nationhood provisions, which speak of the state as the national home and locus of self-determination for the country’s majority ethnic group. Other democracies, in the EU and beyond, have official languages and religions, and use specific ethnic and national symbols to identify themselves. Israel, in short, is hardly unusual or particularly extreme in this respect.

The Polish constitution, for example, speaks in the name of the “Polish Nation,” describes the country’s culture as rooted in “the Christian heritage of the Nation and in universal human values,” and establishes a special relationship with the Catholic Church. It makes Polish “the official language” of Poland and grants automatic citizenship—in effect, a right of return—to “anyone whose Polish origin has been confirmed in accordance with statute.” Once confirmed as Polish, that person “may settle permanently in Poland.” The Bulgarian constitution defines Bulgarian as the official state language, making it the right and compulsory obligation “of every Bulgarian citizen,” even those whose first language is not Bulgarian, to learn and study the language. Eastern Orthodox Christianity is Bulgaria’s “traditional religion,” and individuals of Bulgarian origin are granted a facilitated citizenship process. The Spanish constitution grants national sovereignty to “the Spanish people,” defines Spain as the “indivisible homeland of all Spaniards,” and makes Castilian Spain’s official language. The Indian constitution defines its official language as “Hindi in Devanagari script,” despite the plethora of languages spoken on the subcontinent. The German constitution, also called a “Basic Law,” provides automatic citizenship for former German citizens and their descendants, and defines those individuals as Germans.

Many of the countries that are criticizing the Jewish State Bill have similar laws of their own.

Nor is a strong role for an official religion particularly unusual. In Great Britain, the Church of England is the officially established religious institution. Indeed, the British monarch is required to be a member of the Anglican Church and enjoys the title of Supreme Governor of the Church of England and Defender of the Faith. The Lutheran Church is the “Established Church of Denmark, and as such, it shall be supported by the State,” and the king is constitutionally required to be a member of the Lutheran Church. The Danish state is even permitted to regulate “religious bodies dissenting from the Established Church.” The Lutheran Church is also “the official religion of the State” in Norway, and the king is required “at all times” to profess, uphold, and protect Lutheranism. Additionally, “more than half the number of the Members Council of the State shall profess the original religion of the State.” Non-Lutheran members are constitutionally prohibited from participating in proceedings concerning the state church. Sweden, which grants the Church of Sweden special legal status, requires the king to “always profess the pure evangelical faith,” and a member of the royal family who is not also a member of the Church is excluded “from all rights of succession.”

This list is by no means complete, and does not cover the various laws that many democracies have consecrated in their constitutions in order to preserve the integrity of their national character and culture. In fact, as professor Eugene Kontorovich of Northwestern University has pointed out, the Jewish State Bill “actually does far less to recognize Jewish nationhood or religion than provisions common in other democratic constitutions,” in that it does not designate Judaism as the official state religion or require its heads of state to profess the Jewish faith.

Once all of the above is taken into consideration, it seems that the concerns over the Jewish State Bill are unfounded and its critics mistaken. The bill will not destroy Israeli democracy. It is not outside the norms observed by almost all modern democratic nations. It will not create an apartheid state. And it will not negate the rights of Israel’s minorities. In practice, it will change almost nothing.

So why is the bill still being so strongly criticized?

One telling claim is the accusation by some critics that the bill will create an obstacle to peace with the Palestinians, since it will force them to recognize Israel as a Jewish state as part of a final agreement. In effect, they will have to accept the Jewish historical narrative. But it is difficult to see how this would be an obstacle to any Palestinian government that negotiates in good faith. Tower editor David Hazony has correctly noted that Palestinian recognition of Israel’s Jewish identity and the Jewish historical connection—and resulting national rights—to the Land of Israel would mean a genuine end to the conflict, since it is the core issue behind it. It would aid, not hinder, the establishment of two states for two peoples.

This claim may be mistaken, but it indicates their real problem with the Jewish State Bill: The bill affirms Zionism and its assertion of the Jewish people’s right to establish a state in their ancient homeland, enshrining those concepts in Israeli constitutional law. Unfortunately, many people are uncomfortable with the idea that the Jews are a people no less indigenous to the territory of historic Palestine than the Palestinian Arabs. On some level, they believe that Israeli Jews are in Palestine on sufferance, and not by right, that Israel’s existence is only justified post facto, and not initially just.

They betray this sentiment by reserving for themselves the right of any people to define their own identity, yet they simultaneously deny this right to Israeli Jews. Instead, they consider the Jews to be foreign colonizers, and for these colonizers to set up not only a state, but a state built on a particular historical narrative and dedicated to maintaining a particular identity, is a step too far. The critics, in short, have accepted the ahistorical narrative pushed by many Palestinians and their supporters; a narrative that is used as a political weapon in order to strengthen their bargaining position vis-à-vis Israel. After all, how can foreign colonizers make any demands on natives who are being so magnanimous as to offer these usurpers a piece of their territory? In effect, critics of the bill have decided that the Palestinians have the right to define the identity of the Jewish people and the form of their self-determination.

When the international community made it a legal obligation to establish a Jewish state, it accepted the idea that the Jews had the right to define themselves according to their historical connection to their homeland, in the same way as any other people. But decades of propaganda—and terrorist violence—have weakened the international community’s willingness to live up to this obligation. And so an otherwise benign bill is being decried as if it were the second coming of Jim Crow.

Israel’s response to such claims was given over two millennia ago, in the book of 1 Maccabees: “We have neither taken foreign land nor seized foreign property, but only the inheritance of our fathers, which at one time had been unjustly taken by our enemies. Now that we have the opportunity, we are firmly holding the inheritance of our fathers.” It is only when the international community understands this and chooses to live up to its professed principles, and when the Palestinians come to the realization that they do not have the right to deny another people’s history and identity, that peace will come. If anything, the Jewish State Bill could prove a positive step in that direction.

![]()

Banner Photo: Israel_photo_gallery / flickr