The author of Israel’s most poignant elegy for the kibbutzim speaks out about post-socialist Israel and the powerful continuity of its national ethos. Photos: Aviram Valdman

Novelist, essayist, literary critic, and pianist, Assaf Inbari begins our interview before the server in this trendy coffee shop takes his order, before I take out my notebook, before I ask my first question. He knows what he wants to say.

Inbari is 45-years-old, but with his tight, wiry build, thick black hair, boyish face and bashful grin, he looks considerably younger. He speaks slowly and deliberately, chooses his words carefully, and pauses even at his most emphatic. He smiles often, sometimes with a self-deprecating laugh, as if to puncture his intellectualism. And yet, at times there is a sober, almost wizened tone in his voice, as if he is overburdened by his own thoughts.

We meet at Tzemach Junction in the upper Jordan Valley, not far from the shore of the Sea of Galilee. It is an iconic place in Zionist history. This is where the earliest pioneers labored to create the kibbutz and reinvent the Jewish people. Only fifteen years ago, it was still filled with banana fields and kibbutz factories. Now it’s a mall.

Inbari orders a latte. The sounds of pressurized steam and Israeli pop music provide the background noise to our conversation. Throughout, Inbari willingly discusses his thoughts—but not his feelings—about Israel’s past and future.

Inbari was born only a few miles away on Kibbutz Afikim, at a time when it was one of Israel’s largest, strongest, and richest kibbutzim. Like all kibbutz children of that era, he was raised in a children’s house and went to the regional school. And like many kibbutz members at that time, he enlisted in an elite army unit, though he didn’t last long (he refuses to give details). He completed his military service in the army radio unit, where he was the editor for Alex Ansky, one of Israel’s hippest actors and radio personalities.

After his discharge, Inbari lived in Tel Aviv for nearly a decade, completing a Ph.D. in Hebrew literature at Bar Ilan University. He married, divorced, and then travelled through Holland and Germany for years, studying transcendental meditation.

Today, he rents an apartment on the nearby Kibbutz Degania with his second wife and children, but he is not a member of the kibbutz. He lectures at several Israeli colleges and is widely perceived as one of Israel’s leading social critics. But he is not very popular. He disdains what he sees as Tel Aviv’s post-Zionist zeitgeist; he affirms collectivism at a time when individualism is the Israeli bon ton; and he is proud of his particularist, secular Jewish identity even though globalist universalism is in vogue. It’s not easy to put him into convenient political categories of Left and Right.

Inbari makes a sweeping gesture. “This was once a productive place,” he says, “Now, people don’t want to work. People build things to get rid of them, to sell them, to make an exit, to make more money. There’s no dignity here, no creativity, just how to make a buck.”

But he chose to meet here, I say, not on the kibbutz.

“There is no kibbutz anymore,” he replies.

The remains of Kibbutz Afikim’s once-mighty Kelet plywood factory, starkly visible from the main highway, are a reminder of the kibbutz’s lost glory. Today, Afikim has been privatized, and members earn their salaries outside the community. There are rich people and poor people on the kibbutzim, just like in the cities. They have abandoned the ideal of economic equality.

“Less than a quarter of Israel’s 220 kibbutzim are in any way communal,” Inbari says, “and as we’re speaking, another one has probably privatized itself.”

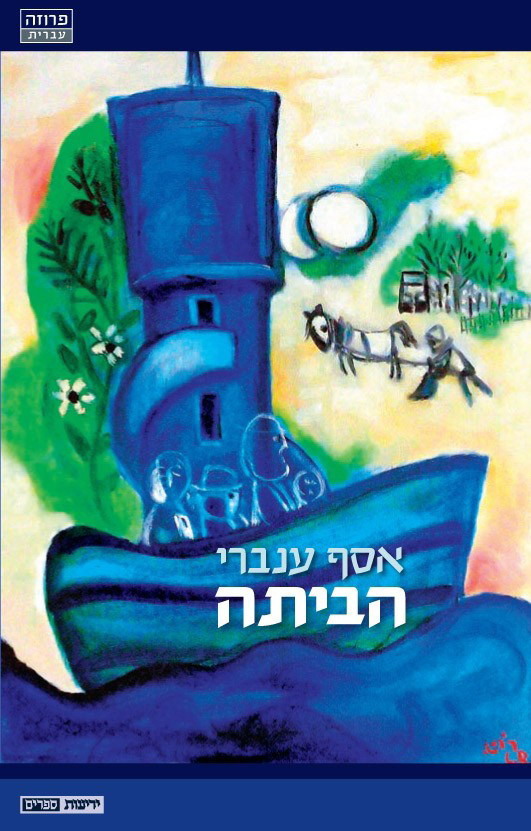

Home, Inbari’s carefully documented yet sparsely written history of Kibbutz Afikim, was short-listed for the prestigious Sapir Prize in 2010. It tells the story of the kibbutz primarily through the lives of seven of the original pioneers—six men and one woman—who founded and built Afikim in the 1930s. Most came from Russia, a few from elsewhere in Eastern Europe, and one from the United States. Inbari uses their real names, even though their families are still alive and some still live on the kibbutz.

“I wrote about the heroes of their time,” he says of his book, “about Zionism, about responsibility and history. These people believed they were doing something wonderful on a global level. And they were right. Throughout the generations, humanity tried to establish idealistic communal societies. We should understand them as people who were enthusiastic, in love with their fate. Their primary experience was one of significance and meaning.”

Yet Inbari sees them as tragic figures.

“Their personal lives were difficult. They suffered losses and pain. And for those who didn’t have the wisdom to die before everything was privatized, they watched their dreams collapse. But they created something, they made history.”

The book is called Home, I say, but can you go home to a place that was never your home?

“Home is the most basic Jewish story,” he answers. “Abraham was called to leave his parents, his home, his civilization, his identity, for something he did not know. As a people, we were always born somewhere else: In Mesopotamia, in Egypt, in Sinai, in Babylon after the destruction of the First Temple, in Europe and the East. But we always came back here—even when we had never been here—at least in our consciousness. We exchanged our birth names for our new identities.”

Inbari writes, he says, in a Jewish style: with terse restraint, few adjectives, and a slightly bemused tone that strays at times into an almost cruel irony. His narrative voice is so minimalistic, so biblical, that it’s almost invisible. It is clear that he deeply admires the people he writes about, some of whom he knew, but he never falls into sentimental pathos. He writes about them in all their greatness, pain, and pettiness, but they are never ridiculed.

One of the most striking moments in Home describes a notorious tragedy that took place on the nearby Kibbutz Ma’agan. On July 29, 1954, 17 people, among them three prominent members of Kibbutz Afikim, were killed and 25 injured when a small airplane crashed into a memorial service for Israeli paratroopers who died trying to save Jews from Europe. It was, and still is, a cause célèbre in Israeli history. Inbari writes,

A few minutes after the ceremony began, Lassia and Clara arrived and found empty seats in the back row. A light plane dived above them and dropped greetings from the President of Israel. The Sea of Galilee was blinding, the plane was blinding, and anyone who wasn’t shading his eyes was applauding. The plane dived sharply. Lassia grabbed Clara’s hand, and the plane crashed into the first rows. Mula, Rachel, Alik, and 14 other guests were killed instantly…. When Nurit and Yossi [children who lost their parents in the crash] came back from summer camp, no one told them. Everyone assumed that they’d understand by themselves. They understood that their father and mother weren’t at home.”

Listening to his own words, Inbari says quietly, “They’re still waiting for someone to talk to them.”

“The founders were deeply flawed people,” he admits. “They were very young, with no experienced adults around, and they were clueless. They paid very heavy personal prices for what they were able to build. And their children paid, too.

“It was tragic, but death was part of their lives. They lost children. They died young. But they had the wisdom and the sense of history to understand that the world wasn’t created for us and it won’t end for us, either. They very personally understood the saying from the Ethics of the Fathers [a book of ancient rabbinical sayings], ‘It is not incumbent upon you to complete the work, but neither are you at liberty to desist from it.’ They didn’t value individual life above all.”

But ultimately, the kibbutz experiment failed.

“Yes and no,” he responds. “The question is, in what context do we think about the kibbutz? If the context is socialism, it failed. It did not create a collectivist, communal society and it was not a just society.

“But if the context is Zionism, if we understand them as they understood themselves, they succeeded. They combined national, cultural and social goals, a workshop for the creation of a Jewish culture and a task force for the creation of the state.

“They made terrible mistakes, of course. But there was also another context: The kibbutz could only succeed in a time when ‘we’ was considered a legitimate way of life. Not like now, when ‘I’ is the only word that is considered important.”

Most of your generation, I point out, the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the founders, left the kibbutz.

“That is proof that they failed as a socialist enterprise. They were the only people anywhere to create a voluntary socialist community, where people could stay or leave. We see that people may want to establish these communities, but the later generations, who don’t benefit from the enthusiasm and the sense of purpose at the beginning, don’t want to stay there.”

You sound angry, I say.

“I am. People in my generation—on the kibbutz and throughout Israel—define themselves primarily as victims. They have developed a moral nihilism. Being a victim replaces the need to take a stand, to make a moral choice. They think of themselves as children, because someone does or did something to them, and never as adults who have to take responsibility for what they do.

“We can’t make excuses for ourselves. We say, ‘If we were just as creative or smart or good or energetic as they were.’ Well, they were also petty and mean-spirited and silly—just like us. They weren’t a generation of people with exceptional talents or qualities. They were a generation of people with exceptional commitment and a sense of responsibility for themselves and for history.

“They were very secular and also very Jewish, because in Judaism there are no exemptions from morality. There is right and wrong, and we are judged according to our acts. We have agency.”

Yet today you live on Kibbutz Degania.

“I guess I’m a field mouse, not a city rat. But I’m not a member of the kibbutz; and anyway, if a kibbutz is privatized, it’s not a kibbutz. But I do live in a community.”

Living in a community, Inbari says forcefully, is the only way to find meaning and significance in life.

“When you live in a community, you choose to contribute—as an artist, a doctor, a plumber, or a politician—because you care. You want your family and community to be happy, you want to defend them, and if you have no choice, you will kill or be killed for them.”

What about the individual responsibility you spoke of earlier?

“‘We’ doesn’t cancel individual responsibility. It increases it. When a person feels a ‘we,’ it’s not something abstract. Living a meaningful life means you are meaningful to someone, and you know that there is something greater, more important than just your own life. And it is the most moral way to live, because you cannot choose your parents, or your children, or your heritage.”

But doesn’t collectivism pose a danger, too? After all, it can lead to fascism.

“Collectivism got a bad rap after World War II and the Holocaust and other atrocities; so rabid individualism has become our new religion. But rabid individualism and rabid collectivism are both an attempt to escape responsibility. Whether we try to absolve ourselves by feeling that we do not belong to anything, or try to absolve ourselves by handing over responsibility to the collective, we are not being human.”

The solution, he says, is nationalism—an unpopular term these days. Especially among most intellectuals, who oppose the current Israeli government’s right-wing policies.

“Nationalism is the golden mean,” Inbari says. “It’s an expansion of family. You care about the people. They care about you and you care about them. That doesn’t mean it’s always pleasant. I’m not being saccharine here. But you invest and you try to make a difference for your family and your nation.”

Which brings him to the topic of post-Zionism.

“There is a culture war raging in Israel,” he says, “and I see myself as a soldier in that war. Post- and anti-Zionists are very vocal and hold positions of influence in the academy, culture and media. They deny the idea of the nation-state and especially Zionism.

“And many of them leave the country because it’s hard to live here. I know how uncomfortable it is. I teach at two colleges, I lecture, I’m 45 years old, and I can barely make a living. I support my family while my wife is studying. I’ll probably never have enough money to buy a house. We’d like another child, but we can’t afford it. And I dread the day when my son becomes a soldier…. Hey, even the weather isn’t comfortable—it’s horridly humid and terribly hot. To be a moral person, you have to choose between comfort and commitment.”

But doesn’t the community have a responsibility to the individual? Doesn’t the government have a responsibility to ensure at least a modicum of economic and social security? Isn’t that what the demonstrations in 2011 were all about?

“I didn’t like those demonstrations,” he responds. “They were a bunch of self-righteous protestors. They were making demands without taking any responsibility for what those demands would cost. They were calling for social justice, but social justice is about the balance between rights and obligations.”

What about social priorities? What about the lack of social mobility, especially for Mizrahim (Jews of Middle Eastern origin)?

“I don’t like a lot of things that the country does,” he replies. “I don’t like a lot of our priorities. I don’t like the occupation. But we are a country in progress. And I believe our leaders are doing the best they can.”

Really? You’re not the least bit cynical about the political leadership in Israel? That’s quite a generous assessment these days.

“Maybe I’m naïve. But I’d rather be naïve than cynical.”

Then Inbari attacks two other sacred cows: Judaism and the melting pot.

“Last year,” he says, “people were very upset when a poll showed that there is no secular majority in Israel. There never was and finally the bubble of that illusion burst. I’m glad, because that illusion has kept us from forging a modern, pluralistic Judaism here in Israel. We need a free Judaism here, but not freedom from Judaism.

“We seculars have abandoned Judaism, just like the ultra-Orthodox abandoned the State. We gave ourselves exemptions from creating a new, vibrant Judaism. Instead of giving in to the Haredim, we should be forging a modern, pluralistic, enlightened halakha [Jewish religious law]. That’s what the pioneers tried to do. They knew that Judaism was never static. Judaism always transformed itself and was relevant. They tried to create a modern, nationalist framework. They invented new rituals, they dealt with day-to-day ethics. They had a form of political theology. That’s what Judaism is supposed to be. We should be confronting—on Jewish terms!—those rabbis who think that Judaism means excluding women or ignoring the Palestinians on the West Bank.

“Moderate and enlightened people—religious and secular—are still a solid majority here. But in a few years, the zealots will become a critical mass. We still have the opportunity to shape Israeli society as a pluralistic Jewish community, but we don’t have much time.”

To achieve this, Inbari says, Israel needs to create a “Jewish melting pot.” It is typical of Inbari to use the term “melting pot,” which is anathema to most progressive thinkers in Israel, because it is usually thought of in terms of attempts to erase Mizrahi identity and remake it in the image of the Ashkenazi Sabra (or, to be more precise, the image of the kibbutznik).

Inbari insists he doesn’t mean “that kind of a melting pot.” He means “a Jewish melting pot.”

“Ben-Gurion tried to force an ‘Israeli identity’ on everyone,” he says. “He wanted to ignore Judaism—both Ashkenazi and Mizrahi Judaism. The founders had some oedipal issues with their parents, but that was their problem, not ours. They cut themselves off from their traditions; which was tragic and heroic, but we don’t have to carry that biographical wound. We don’t need to deny the Diaspora and the identities that all the Jews from all the communities brought with them when they came here. We should be teaching Jewish ways of thinking, Jewish jurisprudence, Jewish modernity, and that way we can build a cohesive society.

“Think about it: How enriching it would be if we all learned Moroccan piyutim [religious poetry]. Or how enriched our education system would be if we included the Haredi value of learning for its own sake. But it didn’t happen because the secularists are as convinced that they know the whole truth as the Haredim are.

“Instead, because so many groups were left out of the so-called melting pot—because it was an Israeli, but not a Jewish, melting pot—we split up into separate groups, with different interpretations of reality, and we are really beginning to hate each other. Multiculturalism is the current bon ton, but what it really means is the politics of crude, unrestrained opportunism.

“We need pluralism. I don’t mean we all have to agree, but we do need the basis for a common argument. We don’t have that.”

Is that why Israelis scream at each other so much?

“Probably. We don’t really have anything to say to each other, so we scream.”

What about the Arab citizens of Israel? We haven’t discussed them at all.

For the first time, Inbari is evasive. “I’m just answering your questions,” he says.

You don’t relate to them in your writings, either.

“I’m not an expert on this topic. And as someone who wants to contribute to the public conversation, I don’t have to talk about everything. But I do think our attitude towards the Arabs is one of the most important challenges to Zionism and Judaism. For 2,000 years, it was pretty easy to be moral. We had no power. You can be moral only if you’re strong, because that’s when you make choices. If you’re weak, you’re passive, you have an exemption, you’re like a child.

“We are a strong sovereign nation. Ignoring the rights of the minority, or throwing them behind fences where you can’t see them, is immoral. But the people who want to create a bi-national state are trying to exempt themselves from the responsibility of being the majority by getting rid of the minority.”

You speak in terms of “us and them.”

“Of course there’s an ‘us and them.’ The identity of the Israeli Arab is based on being part of the Arab world.

“I don’t think there really is a solution. The Arabs should have rights and obligations, as individual citizens and as a collective. But they are not just a minority. They are a largely hostile minority. So being moral means that there is no once-and-for-all solution. We have to constantly make decisions, to work at finding solutions all the time. We will constantly have to examine the proportions and constantly fine-tune. Their status will never be solved, but we will never stop working to find good, fair, moral solutions.”

“That,” he adds, “is the meaning of halakha today. It’s an opportunity, because it forces us to be sensitive at all times. This is a very Jewish way of thinking.”

As we conclude, I note that even though the kibbutz may have failed, or at least ceased to exist, Inbari is very much an heir to their legacy.

He’s writing another book, he responds. It’s his way to make a change, to be an actor in history.

“It’s not about the kibbutz. I’m writing about the Jewish and Zionist story, and about history; not only about the kibbutz, even when I talk about the kibbutz.”

He smiles and laughs that endearing, self-deprecating laugh, telling me the higher thinking and intellectual interview have come to an end. “I have to pick up my kids from school and make dinner,” he says.

![]()

Banner Photo: Aviram Valdman