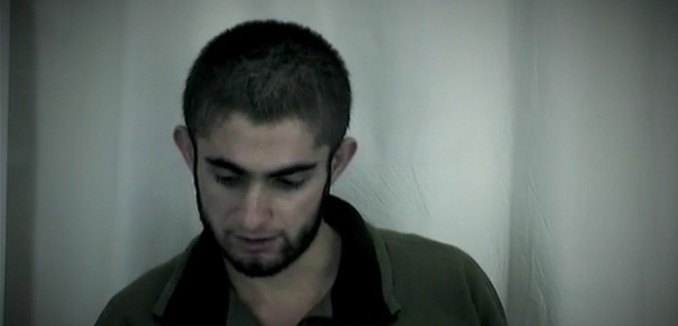

Human rights groups are blasting Iran for broadcasting videos of “apparently coerced confessions” of Sunni prisoners who were recently hanged during “one of the largest mass executions” in Iran’s history, The New York Times reported Thursday.

The videos, shown on state-controlled websites and television since the August 2 executions of at least 20 prisoners from Iran’s Kurdish region, feature the condemned men confessing to membership in a Sunni extremist group and saying that they “would have committed atrocities worse than IS if we had not been stopped,” according to a report by Amnesty International. The prisoners, who also confessed to crimes that took place after they were in custody, are seen calling themselves “‘terrorists’ and ‘heinous criminals’ who deserve their punishment.”

Their confessions were interspersed with clips of unrelated attacks by Islamic State jihadists and accompanied with ominous screen titles including “In the Devil’s Hands” and “In the Depth of Darkness,” Amnesty wrote.

“By parading death row prisoners on national TV, the authorities are blatantly attempting to convince the public of their ‘guilt,’ but they cannot mask the disturbing truth that the executed men were convicted of vague and broadly defined offenses and sentenced to death after grossly unfair trials,” said Philip Luther, who serves as Amnesty’s research and advocacy director for the Middle East and North Africa.

Sarah Leah Whitson, the Middle East director for Human Rights Watch, concurred in an e-mail to the Times. “It seems Iran has joined the region’s propaganda industry, producing slick videos featuring the apparently forced confessions of men they later executed as ‘terrorists,’ bizarrely interspersed with scary videos of Islamic State attacks they had nothing to do with,” she wrote.

Whitson also faulted “Iranian media agencies” for “producing and distributing these videos, which implicate them in a rather macabre and ugly form of abuse.”

Since its 1979 Islamic revolution, “Iran has been among the world’s leaders in administering the death penalty,” the Times observed. The death penalty is imposed not only for capital crimes including murder, but also for drug offenses and the ill-defined crime of “enmity against God.”

Human rights groups have long accused Iran of using torture to extract confessions from prisoners, but efforts to justify executions through a domestic media campaign are relatively new.

The mass executions were condemned by Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein, the UN’s high commissioner for human rights, in August. “The application of overly broad and vague criminal charges, coupled with a disdain for the rights of the accused to due process and a fair trial have in these cases led to a grave injustice,” he charged. One of the condemned men, Shahram Ahmadi, was allegedly tortured and forced to sign a blank document on which his confession was later written, al-Hussein said.

The late Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, at one time considered a likely successor to Islamic Republic founder Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, protested the executions of thousands of political prisoners in 1988. “In my view, the biggest crime in the Islamic Republic, for which the history will condemn us, has been committed at your hands, and they’ll write your names as criminals in the history,” he told an audience of religious judges and prosecutors. Montazeri was the only top official in the Iranian government to object to the executions and was later placed under house arrest until his death in 2009.

There were at least 966 executions in Iran last year, the highest total in ten years, according to the UN. The number of executions in Iran has climbed and reached record yearly highs in each of the three years of President Hassan Rouhani’s tenure. Last year, Shaheed called the execution rate during Rouhani’s administration “an unprecedented assault on the right to life.” Rouhani’s appointed Justice Minister, Mostafa Pour-Mohammadi, earned the nickname “minister of murder” for having overseen the summary executions of tens of thousands of dissidents in the late 1980s.

[Photo: Aparat ]