When Yotam Ottolenghi opened his first deli in London in 2002, he was probably unaware that he was about to launch a food revolution. His Mediterranean emphasis on fresh seasonal vegetable dishes trimmed with Middle Eastern condiments and spices proved so popular that he and his business partner, Sami Tamimi, now preside over an international culinary empire: five constantly packed restaurants and delis in London; five best-selling cookbooks, including the James Beard award-winning Jerusalem; a line of food products available through his website and delis; a regular column in the The Guardian; and of course frequent television and public appearances worldwide.

It’s no overstatement to say that Ottolenghi changed the way we view Middle Eastern cuisine—raising our consciousness above the familiar hummus and falafels—but he also introduced the world to the exciting, experimental cooking that is taking place in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem.

Not since the introduction of fusion cuisines in the 1970s have simple ingredients and traditional recipes been so up-ended and re-invented in unexpected, sophisticated ways. It’s unsurprising that the forces behind this new cooking are emanating from Israel: More than 100 different ethnicities co-exist on a tiny strip of land. You could argue it’s the most multi-cultural spot on the planet. Second- and third-generation descendants of Jewish refugees who arrived from Africa, Central Europe, Russia, Kurdistan, Iraq, Turkey, and beyond are now mingling and intermarrying in the vibrantly youthful urban centers of the country. In the famous markets or shuks—Levinsky in Tel Aviv, Machane Yehuda in Jerusalem—you can sample countless combinations of ethnic food cultures along a single block.

Israel’s top and emerging chefs are those who embrace this fusion and take it to the next level: I’ve written previously about Yuval Ben Neriah, who at Tel Aviv’s Taizu, brings together five different Asian countries’ versions of street food with a Middle Eastern twist; Dan Zoaretz at Dalida, does similarly delicious, mashed up tricks combining Italian, Arabic and French, among many others depending up on his whim; and chefs Moshe Gamlieli and Itamar Navon at Mona in Jerusalem where, equally whimsically, you might sample a menu inspired by Italian, French, and Indian recipes.

Most prominent is Machneyuda, which, upon its founding in 2009, proceeded to turn market fusion into its own distinct restaurant brand. Set on the edge of the sprawling Machane Yehuda in central Jerusalem, the chefs behind what is acclaimed as one of the best restaurants in Israel have captured both the spirit and vibe of the neighboring market while creating a wholly new type of menu.

I described my own experience of dining at Machneyuda here—one unlike I’d experienced anywhere before: The restaurant is small, two-story space that, night after night, is quite literally packed to the rafters; the atmosphere is chaotic and noisy, a factor which would normally cause to me run immediately out the door (if I could get back to the door). It greets you, however, as an orchestrated, merry chaos, like a street party or the happy throb of the market on a Friday afternoon. Wait staff race here and there with trays of delectable foods, the chefs sing out orders like vendors hawking their fresh produce; the diners become participants in this colorful pulsing scene.

Machneyuda serves up its orders on waxed paper, wooden boards, and occasionally old-fashioned crockery—the way you would eat in the market at food stalls or traditional ethnic restaurants (Dalida uses a brown glass plate found in many humble local eateries). The difference lies in the startling parade of culinary creations placed down in front of you: tender octopus with a white potato haroset-chimichurri sauce; three types of raw beef, each completely differently from the next—tartar, tataki, and carpaccio; endless variations of seasonal vegetables in fused sauces and dips, some grilled and reduced to sauces themselves for other dishes, such as a black tahini-chestnut-charred eggplant base for a velvety nugget of drum fish crudo.

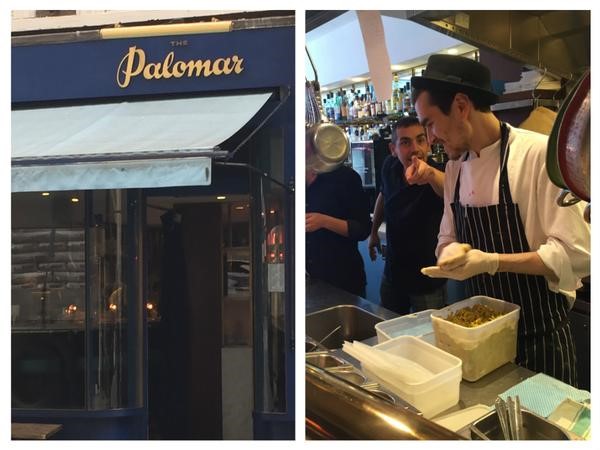

Two years ago, two of the three (now) celebrity chefs behind Machneyuda—Uri Navon and Assaf Granit – followed in Ottolenghi’s footsteps, and opened an outpost in London, called Palomar. Tucked on a side street in Soho, behind the tall lit marquises and gaudy billboards of neighboring Covent Garden, Palomar advertises itself with little more than a blue awning. Show-goers seeking an early dinner could easily walk by it, drawn to the larger restaurants down the block prominently advertising their “pre-theater” menus. This would be a mistake.

The restaurant—composed of a long zinc bar in front of an open kitchen, with a small room of tables in the back—is now almost impossible to get a reservation at unless you are prepared to go there before or after the theater (“We have 5:30 and 9:30 available.”). I managed to grab a stool at lunch time, when pressure on seats was a little more forgiving. The moment I entered the narrow entrance I was struck both by its familiarity to Machneyuda—but also one fused with a distinct London sense of cool: Less chaotic but still merry; chefs calling out orders and occasionally singing along to the hip play list, but in a slightly more restrained way.

Outside and inside the Palomar. A sous chef makes lentil and cod falafels. Photo: Danielle Crittenden Frum

The menu featured a couple of the top hits I recognized from Machneyuda (their famous asparagus and wild mushroom polenta served in a mason jar; a deconstructed version of shakshukit [ground beef kabob], accompanied by warm homemade pita, which amounts to basically the best Sloppy Joe you’ve ever tasted). But in other ways—like Jews throughout history—the Palomar menu had adapted itself to its British surroundings: a delicate crispy chickpea and lentil falafel included cod, like a Middle Eastern version of the UK staple fish cake, made more exotic by a dollop of spicy mango coulis mixed with tahini; transparently thin beet carpaccio with dots of creamy goat cheese, pomegranate seeds and a crunchy toffee-like lentil-hazelnut “tuille”; a dessert menu that featured “Jerusalem Mess,” a play on the popular dessert “Eton Mess,” featuring lebneh mousse, almond crumble, English strawberries, lemon cream, elderflower and apple jelly, and fresh sorrel.

The Palomar’s success led the chefs, together with sibling partners Layo and Zoe Paskin, to launch their second London restaurant in June: The Barbary, located a few blocks from Palomar, on Neal’s Yard in the heart of Covent Garden. It’s even tinier than Palomar, consisting of a single horseshoe-shaped zinc bar surrounding an open kitchen in what was previously a skateboard shop. On the night I visited, the restaurant had only been open for a week-and-a half—but already lines were forming at dinner with customers eager to grab one of the unreservable 24 bar stools. (Learning my lesson from Palomar, I arrived unfashionably early at 5:30 p.m.)

The Barbary takes it name and concept from the historical Barbary Coast, reflecting (according to its press materials):

…the countries from the Atlantic Coast through to the Mediterranean Sea leading to Israel. All these countries have rich culinary traditions, exotic products, flavoursome spices and cooking techniques passed down through generations. Its recipes reflect the sharing between countries and cultures: so The Barbary’s Kanafeh dessert is named for its Israeli roots but could as easily take its Greek name, Kadaif. This culinary heritage is about seasonality—food available at that moment from that piece of land, cooked in the most pure way, with fire, whether it was grilling on coals or baking in ancient clay ovens in the middle of the village. That is the basis of the Barbary: some history, a little bit of romance and a Kitchen Bar.

Indeed, in the center of the tiny space was a fiery grill and a clay oven from which chefs and staff jockeyed around each other to produce plate after plate of delicious—and again, new and different—dishes that fused multiple ethnic cuisines with the motherland influence of of Israel. Presiding over this melee was founding chef Uri Navon alongside Barbary’s head chef Eyal Jagermann, formerly of Palomar. (The pair of them are living embodiment of their culinary mission: Navon’s family descends from North Africa while Jagermann’s grandfather was born in Vienna.)

Despite the restaurant’s newness and microscopic work space, everything ran smoothly: service, as in the other locations, was fast, cheerful, and impeccable; at Barbary, you could see the staff were still building up to the shouts and singing, but for now were rightly more focused on keeping the team and plates moving. Navon paused by my bit of counterspace to chat. He told me he’d been trying five new dishes a day since the restaurant opened, a practice that would ease off once he felt they’d perfected the menu, at least until the next seasonal crop came along.

The chief conceptual difference between the Barbary’s menu and those of Palomar and Machneyuda is that they are less fused and more rugged, or Barbarian if you will. Navon said he was seeking to keep the food “real and accurate” to its culinary origins, a “celebration of the cooking of ancient times.”

So an appetizer of “Masabacha Chickpeas”—an earthier type of hummus served warm, with half of the chickpeas still whole—arrived as I’d experienced it at small cafes in Tel Aviv, except Barbary’s was mind-blowingly good, like the Goddess of all masabachas. Nutty, perfectly textured chickpeas melted into the surrounding swirl of hummus, tahini, and the freshest complement of tomato sauce. It was accompanied by a giant piece of charred naan bread pulled directly from the oven, which I tore and plunged into the masabacha like a savage. Then there were small grilled chicken thighs with crackly, seasoned skin on a bed of sweet onions, simple indeed, but also tender and perfect. A charred eggplant dish was “meatier” than I’d experienced at the other restaurants: it was more like a large cutlet, smoky and soft when you cut it open, served with fresh raspberries and date honey.

Left: The Barbary’s horseshoe bar; Right: my plate of masabacha.

Restaurant photo courtesy of The Barbary.

Even while seeking ancient purity, Navon allowed that he was always inspired and swayed by what he might find in a market on any given day—thus the eggplant, raspberry, and date combo. “We’re very good about fantasizing and imagining,” he said. “I see raspberries and dates sitting side by side; I don’t know what I’m going to do with them, but I know I’m going to do something.”

As the line to the door built, even on a rainy night, Jagermann got busy producing small, pocket-like snacks—Lebanese “arayeses”—and tossed one my way. This was from their “queue menu”—devised to satiate the patiently waiting throngs outside. An arayes is a meat pie traditionally served at weddings: Barbary’s contained minced beef and lamb gently seasoned with cumin, salt, and pepper, encased in a toasted pita crust. Somehow it emerged from being cooked on the grill to be slightly charred on the outside without being overcooked or losing juiciness on the inside. “It took me three weeks to test this,” Navon said. “The meat needed a certain amount of fat so it wouldn’t dry out.”

My husband joined me midway through the meal—he’d not been with me at Machenyuda, but I’d pulled him to Palomar the day before (a second lunch for me there), eager for him to experience what I’d been telling him about since I came back from Israel. He immediately fell into a reverent silence as he tasted and devoured new plates that arrived and re-orders of ones he’d missed—but were too good to miss. This cuisine was, he said happily, like nothing he’d tasted before—and something he could eat every day. “Fresh, new, and inventive. It leaves you feeling wonderful, not overstuffed.”

We’d been together to a couple of Ottolenghi’s restaurants, where we were knocked out—like native Londoners—by the dazzling improvisation on fresh vegetables and Middle Eastern themes. But Palomar, Barbary, and the beloved Machneyuda go even further in their inventiveness. The world will be quick to embrace them too.

“A restaurant is a living thing,” Navon mused. “It always goes forward. Without Ottolenghi we could not have done what we do. In the past 15 years everything has completely changed. London is very supportive of the food.”

And what eventually of dancing on the tables, as occurs on more raucous nights at Machneyuda? Will they import that culture to London too? He smiled and glanced around at his very British clientele. “I don’t think that’s going to happen.”

Danielle Crittenden Frum is a longtime Washington, DC-based journalist and author, and founder of Fig Tree & Vine, a new Jewish-oriented lifestyle and e-commerce site. You can contact her at danielle@figtreeandvine.com.

For more content like this, and beautiful artisanal Jewish products, please visit Fig Tree & Vine, the stylish destination for contemporary Jewish living. Follow us on Instagram @figtreevine and Facebook, or subscribe to our newsletter.

[Chef Uri Navon at The Barbary in London, the latest restaurant creation of a Jerusalem-based group. Photo: Danielle Crittenden Frum]