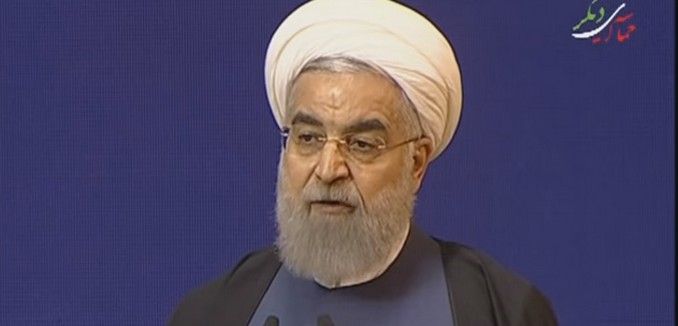

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s scheduled visit to Austria was canceled at the last minute due Vienna’s denial of an Iranian request to clamp down on demonstrations protesting his visit, two leading Austrian media outlets reported on Wednesday.

Rouhani was set to meet and sign a number of bilateral agreements with Austrian President Heinz Fischer on Wednesday and Thursday.

Austria’s leading newspaper Die Presse reported that Iran had demanded the cancellation of the planned demonstrations, which were organized by Stop the Bomb — a coalition dedicated to preventing Iran from developing a nuclear weapon — as well as Kurdish and Jewish groups, last week. However, the Austrian government refused to comply, citing freedom of assembly. In a follow-up report, Die Presse wrote that Iran “dug in its heels” on its demand, while Andreas Pfeifer, chief of the foreign policy desk at Austria’s state television, added that Iran insisted “quite fiercely” that the protests be canceled.

In a statement, the Austrian president indicated that security concerns led to the cancellation of Rouhani’s visit. “Every nation has to decide for itself about the safety and security of its head of state,” Fischer said. “The quality of the relations with Iran won’t be touched by this delay and the cooperation in the realm of politics, business, culture and science will be continued in a comprehensive manner.”

However, according to Austria’s Interior Ministry, there were “no concrete signs of a security threat.”

Iran’s PressTV reported on Tuesday that Rouhani’s visit to Austria had been “postponed to an appropriate time to create better conditions for the visit and and the discussion of issues on which the two countries seek to reach agreements.” No mention was made of security considerations.

A report in Iran’s Mehr news agency on Wednesday only cited the statement from Fischer’s office when mentioning the reason Rouhani’s trip was cancelled.

Rouhani’s trip to France in January was met with protests by thousands of activists who blasted Iran’s violations of human rights.

Rouhani rose to prominence in 1999 by opposing student demonstrations against the Iranian regime. Suzanne Maloney, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, recounted in 2014 his role in shutting down the protests:

Both leaders’ themes were echoed by Hassan Rouhani, then deputy speaker of Iran’s parliament and secretary of the Supreme National Security Committee. Rouhani was one of the head-liners at a well-scripted counter-demonstration organized by the regime one week after the dormitory raid. To a large, enthusiastic and well-compensated crowd, Rouhani inveighed against the protests, calling the organizers “bandits and saboteurs” and promising that Tehran would “resolutely and decisively quell any attempt to rebel.”

His pledge that the protest leaders would be charged with mohareb (enemy of God) and mofased (corrupt on earth) – crimes punishable by death in the Islamic Republic – drew some of the first international press attention for the then little-known lawmaker. However, he also reiterated promises to investigate the dormitory raid and lauded the “outstanding role” of students in Iran’s revolutionary history.

Rouhani was not the only Iranian official who achieved newfound prominence during the crisis. Also notable during this episode was the role of the Revolutionary Guard and senior military commanders, who issued an unprecedented warning to Khatami. Like Khamenei, the commanders saw the episode as “the footprints of the enemy in the aforementioned incidents and we can hear its drunken cackle.” The injunction — which was signed by, among others, current Tehran mayor and leading 2013 presidential contender Mohammad Baqr Qalibaf — admonished Khatami that “our patience has run out. We cannot tolerate this situation any longer if it is not dealt with.” The threat of military intervention proved a harbinger of things to come, as the Revolutionary Guard transformed into a political and economic powerhouse.

[Photo: AFP news Agency / YouTube ]