As the clock struck midnight in Buenos Aires last night, street celebrations broke out in various parts of the city. Residents banged pots and pans, waved the Argentine flag, set off fireworks, and sang the national anthem. Similar scenes were recorded in many other cities throughout the country.

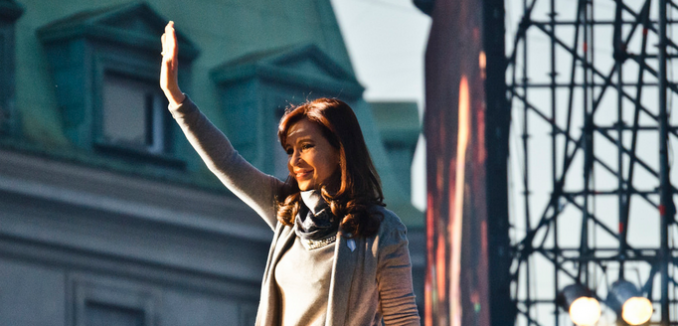

The reason for all this joy was the end of President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s second and final term in office. Since the return of democracy to Argentina in 1983, the departure of presidents from office has occurred in a variety of circumstances, but has never before sparked spontaneous street festivities.

There are many reasons why Fernández de Kirchner’s departure from the political scene is significant, but just one will be of concern here: her government exemplified the possibilities and limits of the new anti-Semitism.

Fernández de Kirchner’s first term in office began in 2007. For the first three years she was accompanied in power, if not in office, by her husband and predecessor, the late Néstor Kirchner. Though no paragon of liberal virtue, his astuteness and caution with regard to international affairs and (at least by comparison to his wife) basic sense of decency had led to the creation of a Special Prosecutor’s Office headed by Alberto Nisman to investigate the 1994 AMIA bombing. In due course, international arrest warrants were issued for a number of senior Iranian officials in connection with the atrocity. Kirchner highlighted the warrants every year from the podium at the United Nations General Assembly, as did his wife in her early years in office.

The death of Néstor Kirchner in October 2010 precipitated the beginning of a shift towards Iran in Argentina’s foreign policy and a radicalization of Fernández de Kirchner’s rhetoric. This was based on a conspiratorial worldview that saw Argentina as the victim of plots by mysterious global forces, many of them led by Jews. This shift eventually led to the signing of a Memorandum of Agreement with Iran in January 2013, supposedly to investigate the AMIA massacre, but in fact designed to guarantee impunity for the wanted Iranians. This was accompanied, on the part of Fernández de Kirchner, by frequent mentions of her determination to find out who those really responsible for the massacre were – and the sotto voce implication that the official representative bodies of Argentina’s Jewish community might have had some role in it. The likely murder of Nisman in January this year only exacerbated this rhetoric.

So far this fits well with the classical mold of anti-Semitism, though this isn’t the anti-Semitism of old, as The Tower’s Ben Cohen has pointed out. With the new anti-Semitism, Jews are welcome to participate as long as they have the right opinions. Fernández de Kirchner appointed Jews to senior cabinet positions, and one of them, Foreign Minister Héctor Timerman, was a key negotiator of the pact with Iran. A chorus of Jewish intellectuals and public personalities supported the signing of the pact, as did a number of the families of the AMIA massacre victims.

This is more than the just another example of the traditional role of the Jewish witness in anti-Semitism, such as when in medieval times a Jewish apostate would be produced to argue with a rabbi. And nor is it comparable to previous cases of Jewish assimilation, such as that of assimilated Jews in Germany, who felt themselves to be fully German and loyal to the state but yet were never really accepted as being part of the nation by German anti-Semites.

As far as I can judge, the bulk of Argentines with anti-Semitic views accept Jews with similar opinions as being fully Argentine. Moreover, the number of Jewish supporters of Fernández de Kirchner’s policies towards Iran was just too big and their position in public life too prominent for them to be regarded just as examples of “good Jews,” though of course some would be delighted with that role.

Indeed, it might be argued that the very success of the assimilation of Jews into Argentine life has provided some of them with a solid emotional base from which to support the execution of objectively anti-Semitic policies, such as the understanding with Iran, and to cheer endless speeches about the dastardly maneuvers of international bankers. Generations of universal state education, strict monolinguism in the public sphere, and, until the early 1990s, compulsory military service for men had their desired effect; they made Argentines out of immigrants from all over the world, and of Jewish ones too. The role of Peronism is also important. As recent work by Israeli historian Ranaan Rein has demonstrated, the rise of Peronism was crucial to the inclusion of Jews in political and public life in Argentina.

So while Ben Cohen was right to point out that anti-Semitism has become a new social movement, comparable in some respects to environmentalist and animal welfare movements, and that Jews with the right opinions are welcome to join it, there is more to it than that. At least in the Argentine case, the very success of its assimilation of Jews, of how it has made Argentines of them, has allowed some of them to march shoulder to shoulder with anti-Semites and to sit at the cabinet table with them too.

But the Jewish experience in Argentina under the governments of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner also shows the limits, at least in the case of democratically-governed countries, of asking whether this or that government or society is or is not anti-Semitic; anti-Semitism and successful Jewish life can coexist, and, as I have suggested, certain aspects of the latter may even facilitate the former.

Capitalism, whatever else it is, is not a conspiracy, and it’s not a conspiracy run by Jews either. Cristina Fernández de Kirchner departs from office against a background of roaring inflation, stagnant growth and Central Bank reserves at historic lows. So while the emotional satisfaction derived from anti-Semitism is very great, even for some Jews, it’s a poor way of explaining how the world works. The economic catastrophe of the latter years of Kirchnerismo explain the defeat of its candidate, Daniel Scioli, and the triumph of Mauricio Macri. Hence the enormous sense of relief at her departure and the surge of hope for the future exemplified in last night’s celebrations.

For a more thorough look at the history of the AMIA attacks and Argentina’s shameful refusal to bring its perpetrators to justice, read Has Argentina Turned Against Its Jews?, written by the author for the October 2014 issue of The Tower Magazine.

[Photo: Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación Argentina / flickr ]