The biggest concession that Ayatollah Ali Khamenei won in Iran’s nuclear negotiations with the West was the “sunset clause,” after which there “would be no legal limits on Iran’s nuclear ambitions,” Ray Takeyh, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, argued Sunday in an op-ed published in The Washington Post.

Takeyh noted that “[a] good agreement for the supreme leader, however, has to be technologically permissive and of a limited duration,” and explained how Iran achieved those goals.

Since the exposure of Iran’s illicit nuclear program in 2002, its disciplined diplomats have insisted that any accord must be predicated on the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which, in their telling, grants Iran the right to construct a vast nuclear infrastructure. In exchange for such a “right,” they would be willing to concede to an inspection regime within the leaky confines of the NPT. And for much of that time, the great powers rebuffed such presumptions from a state that has been censured by numerous U.N. Security Council resolutions and denies the International Atomic Energy Agency reliable access to its facilities and scientists.

As Khamenei held firm, however, the great powers grew wobbly. With the advent of the Joint Plan of Action in November 2013, Iran’s fortunes began to change. Washington conceded to Iran’s enrichment at home and agreed that eventually that enrichment capacity could be industrialized. The marathon negotiations since have seen Iran attempt to whittle down the remaining restrictions, while the United States tries to reclaim its battered red lines. For Khamenei, the most important concession that his negotiators have won is the idea of a sunset clause. Upon the expiration of that clause, there would be no legal limits on Iran’s nuclear ambitions. If the Islamic Republic wants to construct hundreds of thousands of sophisticated centrifuges, build numerous heavy-water reactors and sprinkle its mountains with enrichment installations, the Western powers will have no recourse. And once Iran achieves that threshold nuclear status, there is no verification regime that is guaranteed to detect a sprint to a bomb. An industrial-size nuclear state has too many atomic resources, too many plants and too many scientists to be reliably restrained.

Takeyh observed that “as Khamenei presses toward an accord that will place him in an enviable nuclear position, he can also be assured that technical violations of his commitments would not be firmly opposed. Once a deal is transacted, the most essential sanctions against Iran will evaporate.” Takeyh also observed that “in a region where many dictatorial regimes have collapsed, the Islamic Republic goes on,” and credits Khamenei’s negotiating skills for this outcome, as “‘he has routinely entered negotiations with the weakest hand and emerged in the strongest position.”

Though the op-ed was published prior to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s historic address before Congress yesterday, the history Takeyh recounts anticipated the “two concessions” Netanyahu critiqued in his speech.

That concession [keeping its nuclear infrastructure in place] creates a real danger that Iran could get to the bomb by violating the deal.

But the second major concession [the sunset clause] creates an even greater danger that Iran could get to the bomb by keeping the deal.

Takeyh’s current concerns about Iran’s nuclear program mark a significant shift in his views. Ten years ago, Takeyh argued that there was no reason to fear Iran, as “its foreign policy is no longer that of a revolutionary state,” and thus, no longer a global threat.

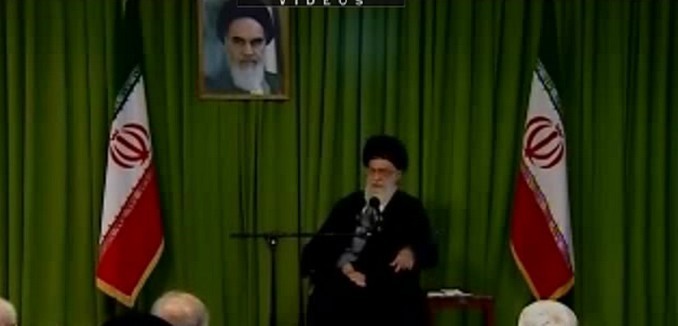

[Photo: Manuchehr lenziran / YouTube ]